Procurement: Paper Chase

25 Jan 2018

If one word is likely to strike fear among architects then procurement is likely top the bill. Bennetts Associates director Rab Bennetts has suffered his own fair share of such tribulations. Urging the profession to mind its p’s and ppq’s no more Bennetts bravely ventures into a Kafkaesque world where bureaucracy, red tape and endless questionnaires hold sway. Here he puts forward the case for new metrics such as awards, references and a commitment to younger practices.

Procurement is one of those words guaranteed to make architects - and many others in the design and construction industry - froth at the mouth. It’s now more than thirty years since I set up Bennetts Associates and procurement processes have had a greater negative impact on the architectural profession than anything else in that time.Gone are the days when an enlightened patron for a college, gallery or theatre can interview a shortlist of architects and make their choice based on trust and an understanding of their approach. Gone are fixed fee scales of course, but so too are all attempts to provide sensible guidance. Gone are the local authority architects departments, who might have been the most suitable vehicles for many public projects.

The values of the market dominate procurement processes and much else. Now there seems to be no limit to the extent that architects will undercut each other or give away vast amounts of intellectual capital for no fee. Those who appoint architects, who now include contractors as well as direct clients, often feel able to cherry-pick the architects’ duties, undermining the meaning of a proper professional service.

None of these observations are new but I wonder if the examinations of the Grenfell Tower disaster and the Edinburgh schools construction problems will prompt some self-examination by architects, clients and their advisors alike. Add in Brexit and this is a highly appropriate moment to question how architects are selected and the impact of professionalism on design.

Whereas private sector selection processes have far more scope for clients to use their judgement, it’s the public sector, worth 40% of the total market, where thirty years of changes to the architect’s role, remuneration and status have had the greatest influence on general attitudes to procurement. Younger or smaller practices have come off worst, but everyone has suffered from the layers of unnecessary bureaucracy, including clients who are often deprived of the best possible building.

At the heart of his bureaucratic quagmire is the Official Journal of the European Union, which is the launch-pad for competitive selection processes where public money is involved. I’ve heard it said that Brexit will free us from OJEU, but doesn’t the problem lie instead with the peculiarly British approach to the ticking of boxes? British civil servants, once famous throughout the empire for their administrative skills, are extremely unlikely to ditch a system of accountability so painstakingly invented for public sector procurement.

Much of the guidance on scoring systems for OJEU processes emanates from the Treasury in fact, not Europe, where there are alternative ways of choosing architects. British assessors love empirical, hard-to-argue-with scoring systems even when they are obviously producing unwanted results.

By way of example, the quality:cost ratios such as 70:30 or perhaps 60:40 might seem benign, but have become a parody of criteria that have little to do with architectural skill. In particular, the cost element can see huge disparities between architects, such that the lowest fee dominates quality even when the ratio suggests otherwise. As Pevsner once remarked, “the English will spare no expense to do something on the cheap”! (Sadly, I suspect he would have included the Scots, Welsh and Northern Irish too.) This is not an attitude that will disappear with Brexit.

Challenging this fixation with lowest cost or risk is a huge task, but that’s the opportunity presented by the triple whammy of Grenfell, Edinburgh schools and Brexit. When a public sector client needs advice to kick off the selection process, the die is cast when they first go to a lawyer, quantity surveyor or project manager. As a result, the scoring systems will fail to reflect the real qualitative differences between architects, the needs of the project and the true costs over time. In my view, this can only change if clients are able to heed advice from those who understand better the role of the architect and the importance of design. A few practical examples provide real examples of another way.

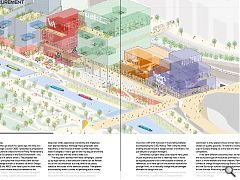

The cultural complex in the Olympic Park is a huge project demanding a large team, but the OJEU notice included a call for young firms to have a role within any multi-practice consortium. Single firm proposals didn’t make the shortlist and the winning consortium (led for practical reasons by Aecom) included Allies & Morrison, O’Donnell + Tuomey and a young Spanish architect.

Another example involves a Scottish higher education institution which tackled the troublesome fees issue by eliminating the highest and the lowest on the basis they were, respectively, unaffordable or unrealistic, so the choice could be made largely on quality as the remaining practices were commercially close together.

In other examples, not all in UK, the fee was a fixed sum, with the contest based on an approach to design and a hefty percentage of the final score being reserved for the interview. This allowed the final assessment to examine how the team worked with each other and with the client.

On another very significant London cultural project, the 30% commercial element was split equally between the fee and the resource. As a result, a low resource with a poor score would counter-balance a low fee with a high score, thereby eliminating another of the inherent contradictions in many financially-biased scoring systems.

The point of raising these examples is to demonstrate that alternative criteria are already available that could avoid the most common injustices, such as the requirement to have recently built three similar projects or to have absurdly high levels of P.I. insurance cover. All it takes is for the initial advisers to properly understand the nature of the project and the role of the architect from the first client conversation onwards.

Back in the mid -‘90s I was invited by the then President of the RIBA, Frank Duffy, to overhaul the competition system as the arrival of Lottery-funded projects was causing real concern about the amount of speculative work. The result was a series of competition guidelines that was adopted by the two Government departments that looked after architecture and planning. These guidelines had a reasonable impact for a while and it proved to me that positive campaigning combined with practical proposals could be well received by the public sector. More recently Willie Watt did much good work for the RIAS in this area, so maybe what we need is a full time campaigner with more time at their disposal than a short-term appointee.

I had another go about four years ago, this time as a Trustee of Design Council CABE. I presented a proposal for revised procurement criteria to the All Party Parliamentary Committee for Excellence in the Built Environment - (no, I hadn’t heard of it before, either!). The proposal was based on the principles that the primary client adviser should be a design adviser or architect (of which Design Council CABE and A&DS both have a pool to draw from), and that selection criteria should be relevant to the design of the project. The presentation also highlighted the iniquitous scoring systems that currently favour large over small, experience over ability and cheapness over appropriateness. Although these proposals were welcomed, it was the lack of follow-up that meant they weren’t adopted; I had to get on with my day job and there was no-one else with the time to take it on.

The key point I learned from these campaigns, backed up by legal advice, is that selection criteria can be flexible to suit the circumstances but they have to be clearly stated at the outset of the selection process. Transparent accountability when it comes to spending public money can’t be avoided, nor should it be as the Garden Bridge fiasco exemplified, so once the process is started it must stick with what was said in the briefing material accompanying the OJEU Notice. That’s why the initial briefing should include a design adviser or architect, not just lawyers or project managers.

Sometimes a project really does require many years of past experience but that is relatively rare; it would be equally possible to list criteria based on awards, or references, or to have part of the shortlist reserved for younger firms, or to radically change the percentages allocated to design and cost.

Another possibility is to adopt something like the ‘Brooks Method’ used in the U.S. whereby the fee submission is only opened once a winner has been chosen on quality grounds. I’m told this is sometimes used in Europe already, as is the idea of a fixed fee for all competitors.

If we want different outcomes, then, we need to change the source and type of the advice provided to clients so that it is more relevant and more creative. Perhaps the climate of change brought about by Brexit, Grenfell Tower and the Edinburgh schools closures will provide the chance to turn the tide. After thirty years in practice observing at first hand the erosion of the architect’s role, a re-think can’t come soon enough.

|

|

Read next: Doon the Watter: Seaside Recovery

Read previous: Park of Keir: Back and Forth

Back to January 2018

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.