Park of Keir: Back and Forth

25 Jan 2018

As Judy Murray’s back and forth volley with Stirling planners ends in game set and match for her Bridge of Allan tennis academy Mark Chalmers sieves through the accompanying racket of a tortuous consultation process to establish the merits of a scheme which continues to divide opinion like no other.

What the tabloids call “Judy Murray’s Tennis Academy” at Park of Keir, just outside Dunblane, has been granted planning permission by the Scottish Government. When it was refused last year by Stirling Council’s planning committee, the newspapers noted that the £37 million scheme received more than 1,000 objections but only 45 letters in support.Many criticisms were raised over “dog whistle” issues – the destruction of the Green Belt, a lack of affordable housing, plus local roads, health centres and primary schools which couldn’t cope with more people. Underlying those are contentions which go to the heart of the Planning process.

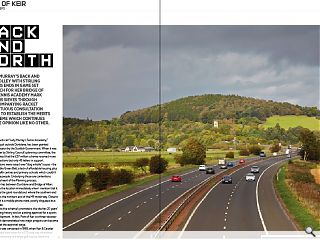

Park of Keir lies between Dunblane and Bridge of Allan: you’ll recognise the location immediately when I mention that it lies right beside the giant roundabout where the southern end of the A9 meets the northern end of the M9 motorway. Close to the roundabout is a mobile phone mast, poorly disguised as a Wellingtonia tree.

According to the scheme’s promoters, the site has 20 years’ worth of planning history and an existing approval for a sports and hotel development. In fact, Park of Keir is a three-decade-long saga which demonstrates how major projects can become bogged down at the approval stage.

The project was conceived in 1988, when Keir & Cawder Estates presented their vision for a 370 acre site christened “Park of Keir”, consisting of a large golf course, hotel and housing development. Superficially, it was not so different from the scheme today – although the balance of the constituent parts has shifted.

Park of Keir is also part of the continuing story of how New Money has usurped Old Money. The Stirling family first appear as landowners in the twelfth century. During the reign of William the Lion, they acquired the estate of Cawder (the modern Cadder, near Bishopbriggs) which stayed in the family for eight centuries; Keir was acquired in 1448 from an ancestor of the Earls of Rothes.

According to the Scotsman, the laird during the mid 20th century, Lt.-Col Bill Stirling, was a high stakes gambler. Perhaps the stakes were too high: in the early 1960’s, 5,500 acres of farmland around Cadder were sold off to an investment firm. Then 15,000 acres at Keir were sold around 1977, including the family seat, Keir House. By 1988, the Herald noted that Keir & Cawder Estates Ltd owned only 2,500 acres in Stirlingshire and Perthshire.

When Park of Keir made the news, the tabloids were quick to point out that Bill Stirling was in the SAS during World War Two – his brother David founded the regiment – and his son Archie, the current laird, was once married to Diana Rigg. They also reported that Archie founded a right-wing political party in the James Goldsmith mould.

So much for human interest, but the newspapers missed the point that land is a great storehouse of wealth and perhaps the surest way to preserve it. The corollary is that the break-up of Keir & Cawder Estates during the 1960’s and 70’s was the destruction of that particular family’s fortune.

Meantime, the Dunblane locals weren’t impressed by the first set of proposals. They grew afraid that the project would “merge [Dunblane and Bridge of Allan], destroy village life, and impose dreaded ribbon development.” Opposition was organised, beginning with SPOKE – Stop Park of Keir, followed by RAGE – Residents Against Greenbelt Erosion, and currently Friends of Park of Keir, which doesn’t have a pithy acronym.

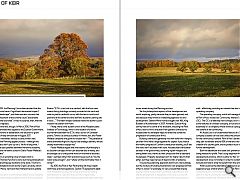

In response, the applicants emphasised that the agricultural value of the land was poor, the houses would be built at low density and screened by trees. The golf course would improve the environment, Keir & Cawder claimed, as would a butterfly farm. Finally, they also wanted to build an interpretation centre to explain the importance of agriculture and the countryside to townsers.

When the application was lodged in 1989 with Stirling District Council, it comprised a business park, interpretation centre, filling station, five star hotel, golf course and 220 luxury homes. Due to the size of the development, it was called in by Central Regional Council and it went to local inquiry in 1991. The reporter recommended against Park of Keir, and the Secretary of State for Scotland agreed with him at appeal in 1993.

As a result, the project stalled and Keir & Cawder Estates sold the land and the project on to A & L King. While Keir & Cawder are one of Scotland’s oldest-established landowners, King Group are relative newcomers. The firm was founded in the 1960’s by Duncan King’s father, but it’s only in recent decades that the firm has become a land and property developer.

In 2002, KW Properties (a joint venture between A & L King and Kilmartin Properties), lodged a new application, to build a 200 bedroom hotel, and an 18-hole golf course. There was a second public inquiry in 2004, and this time the reporter found in favour of the applicant. In 2005, outline planning permission was granted for a 150 bed hotel, plus golf course and clubhouse at Park of Keir.

In 2009, an application to renew the 2005 approval was approved by Stirling Council, as the authority had now become, but that lapsed before any work began. So the saga continued, and three years ago the project gatecrashed the world of celebrity, which guaranteed it much more publicity than your average development attracts.

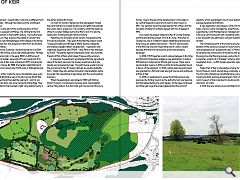

A new application was lodged in 2014, this time including a hotel, a Tennis Centre managed by Judy Murray, a Golf Centre supported by Colin Montgomerie’s management company, and a 150 acre community park with woodland walks. In addition, a new bike path was planned to connect Dunblane and Bridge of Allan.

The contentious parts of the scheme are predictable. This iteration of the scheme included 100 luxury homes which were proposed as an “exceptional case” in Planning terms, to subsidise the construction of the tennis and golf facilities. Knowing how the Planning process works, the first application sometimes consists of a “strategic” scheme which can be negotiated down – so 100 houses were later reduced to 19 houses.

Finally, Park of Keir is intended as a home for the Murray Tennis Museum, which sounds like a universally good thing. The Chris Hoy Velodrome notwithstanding, we’re hopeless at marking Scottish sporting achievements: think of the tiny one-room museum at Duns devoted to double world motor-racing champion Jim Clark.

In 2014, the new scheme was submitted to Stirling Council. In December 2015, the Planning Committee decided that the development could have a “significant detrimental impact” on a “sensitive landscape”, and there was also concern that the housing component of the scheme could “exacerbate affordability in the local area”. It was no surprise, then, that the application was rejected.

That wasn’t the end, though. In March 2016, Park of Keir Partnership submitted their appeal to the Scottish Government, and after a 18 months of deliberation, the decision to grant permission was finally announced in August 2017.

The project warranted serious scrutiny while it was going through the Planning appeal process – although the architecture press didn’t pick up on it. Yet for a long time, I struggled to see past parallels between the tennis academy at Park of Keir and the tennis school in David Foster Wallace’s book “Infinite Jest”.

Infinite Jest is a sprawling novel of ideas which is reminiscent of Thomas Pynchon’s work, but more philosophical in tone. There are three key locations in the book. The first is a man-made wasteland known as the Great Concavity, which spreads across Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire and upstate New York.

The second location is the fictional Enfield Tennis Academy (E.T.A.), a series of buildings located on top of a hill in suburban Boston. “E.T.A. is laid out as a cardioid, with the four main inward-facing buildings convexly rounded at the back and sides to yield a cardioid’s curve, with the tennis courts and pavilions at the center and the staff and students’ parking lots in back …” The heart-shaped cardioid marks the author’s post-modern fascination with form.

Finally, there is the student union of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which is the location of a tennis tournament between the E.T.A. and a bunch of Canadian youths. Tennis is a serious business in Infinite Jest, and Foster Wallace compares the game to nuclear war – “The parabolical transcontinental flight of a liquid-fuel strategic delivery vehicle closely resembles a topspin lob.”

Foster Wallace argues that the essence of philosophy is to discover concepts which can describe bits of reality, and encourages us to critique the world on the level of abstract ideas – perhaps rather than practical issues such as “are the roads wide enough?”, and “where will the stormwater flow in winter?”

By 2016, the Park of Keir Partnership felt they’d dealt with those practical questions. Section 75 agreements dealt with affordable housing and school provision by making contributions of £241,000 and £257,000 respectively. Environmental and traffic impact assessments dealt with other issues raised during the Planning process.

Yet the philosophical aspects of the development are worth exploring, partly because they’ve been ignored, and also because they hint at an interesting approach to land development. Stewart Milne Homes bought over A&L King Builders of Auchterarder in 2007. However, Duncan King cannily held on to some of his landbank, including the Park of Keir, and his firm’s evolution from general contractor to housebuilder to developer helps to reveal the sometime progression of construction firms.

Building contractors generally live with wafer-thin margins, yet their firms have a large appetite for capital. If you look at the woeful progress of Carillion’s share price recently, you’ll see that risks don’t decrease with scale. Housebuilders fare better (at least in the good times), achieving higher margins and taking fewer risks, thanks to their production line of standard housetypes. Property developers aim for higher returns than either, but they need nerves of steel and lots of patience.

The previous planning approvals didn’t turn into buildings, but the mixture of funding mechanisms now proposed at Park of Keir is novel. For example, it’s very unusual that anyone buying a home would have to purchase a debenture in the overall development. A debenture in this case is a one-off payment which will only be recovered when the property is sold – effectively providing an interest-free loan to Park of Keir’s operating company.

The operating company, which will manage the facilities at Park of Keir, would be a Community Interest Company (CIC). The CIC is a relatively new concept, and it combines some features of a limited company, a trust and a charity – but essentially it’s a company whose revenue is ploughed back for the benefit of the community.

An Asset Lock is a fundamental feature of a CIC: so that the company’s assets can’t be sold unless the proceeds are used for the community’s benefit. Park of Keir’s developers have said they plan to transfer around 85% of the land into a CIC for the creation of a country park, and to protect much of the site from further development.

Both the debenture and asset lock prevent assets being realised for profit. That’s a big departure from normal development practice, which is either to “flip” or sell on the development once it’s finished in order to crystallise a profit, or to build and hold in order to benefit from the rental yield.

What could be the alternative? Without an extremely aggressive type of land reform, which took Park of Keir compulsorily into community ownership, the proposal to sign part of it over to community use through the CIC sounds like a workable compromise. Without it, Park of Keir was in danger of becoming a particular kind of Great Concavity – a site neutralised by years of Planning disputes.

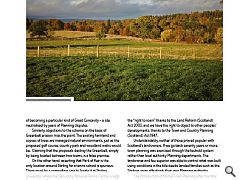

Similarly, objections to the scheme on the basis of Greenbelt erosion miss the point. The existing farmland and copses of trees are managed natural environments, just as the proposed golf course, country park and woodland walks would be. Claiming that the proposals destroy the Greenbelt, simply by being located between two towns, is a false premise.

On the other hand, asserting that Park of Keir is the only location around Stirling for a tennis school is spurious. There must be a compelling case to locate it at Stirling University, where the Gannochy National Tennis Centre, a High Performance Sports Science and Sports Medicine Facility are already located

On reflection, Park of Keir isn’t really about jealousy over the Murray family’s success nor whether the scheme’s promoters are millionaires – although the objectors have raised this issue on social media. Neither traffic levels on Keir Roundabout, nor development on the Greenbelt, are defining issues. In fact, I believe land tenure lies at the heart (or perhaps cardioid) of the issue at Park of Keir.

In recent decades, the Planning process has become a proxy for the struggle to exert control over something you don’t own, but nonetheless have an interest in. We have the “right to roam” thanks to the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003, and we have the right to object to other peoples’ developments, thanks to the Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1947.

Understandably, neither of those proved popular with Scotland’s landowners. If we go back seventy years or more, town planning was exercised through the feuhold system rather than local authority Planning departments. The landowner and feu superior was able to control what was built using conditions in the title deeds; landed families such as the Stirlings were effectively their own Planning authority.

The introduction of formal Town Planning after the War, and the abolition of the feudal system a few years ago utterly changed the game. According to David Foster Wallace, tennis is warfare: but Park of Keir proves that the Planning process can be a battle of attrition too, and it raises some fundamental questions about the exercise of democracy during the development process.

Whose land is it, practically speaking? Should developers be able to do whatever they want on their own property – or conversely should third parties be able to influence or even block developments on land they don’t own? That’s a vast contention which has yet to be satisfactorily resolved – the Great Concavity at the heart of the Planning process.

|

|

Read next: Procurement: Paper Chase

Read previous: Housing Crisis: The New Normal

Back to January 2018

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.