Housing Crisis: The New Normal

24 Jan 2018

The abject failure of the UK to fulfil the most basic need of its population, housing, has troubled politicians of all shades for generations. With seemingly no easy solutions on the horizon architect and Timber Design Initiatives director Peter Wilson grabs the bull by the horns to argue for a radical rethink of how we approach the issue, alighting on a collective custom build project in Portobello for inspiration.

The provision of housing in the UK - or the lack of - is, without doubt, one of the biggest political issues of our time, shaded only by the unfolding catastrophe of Brexit and, in England and Wales, by the seemingly inevitable collapse of the NHS south of the border as a publicly-funded, free at the point of use, provider of medical support to the nation’s population.A controversial statement perhaps, but when the UK Government itself has published a paper entitled ‘Fixing our Broken Housing Market’ (February 2017) you know there is a systemic problem but which, with only three pages of the 104 page document given over to affordable housing and a further three to issues of sustainability, it sadly fails to answer. The clue lies, perhaps, in the use of the word ‘market’ and the country’s long-term over-reliance on the role of volume house-builders to deliver the huge numbers of homes now required on an annual basis. Meeting the demands of a population conditioned since 1980 by a Housing Act that introduced the notion that the Right to Buy as being somehow a Human Right, as well as by significant changes in national demographics has undoubtedly complicated matters.

Not that one would notice any evidence of wide-ranging demographic engagement in the estates of new homes emerging on vast swathes of land to the south of Edinburgh - marketed as 3-4 bedroom luxury homes, the needs of the elderly, the first time buyer, the single parent family and others with incomes of less than £70,000 a year are not the natural hunting grounds for the 20 or so volume house-builders that dominate housing provision in the UK. Tasked with delivering 250,000+ homes per year in England and Wales and more than 50,000 in Scotland, their dominant position in the industry is entirely unmatched by any resolve to meet the challenge. Year-on-year, the numbers of new homes built barely reaches 60% of the requirement, resulting in an exponential annual increase in the gap between demand and delivery.

Other factors, of course, impact on this too: difficulties in obtaining mortgages in the post-2008 economic climate, for example, despite banks being encouraged by various government incentive schemes to widen lending: ‘Help to Buy’ - as widely predicted - simply saw the price of new-build flats inflated in response. That the money from these initiatives has been hoovered up by a grateful housebuilding industry can readily be demonstrated by the stratospheric bonuses the major companies have recently announced for their chief executives: Jeff Fairburn, the now-departed boss of Persimmon trousered an astonishing share bonus of £110m before taking his leave, whilst the CEOs at Berkeley Group, Taylor Wimpey and Barratt Homes are in line for £5.5m, £2.1m and £1.7m respectively under Long Term Incentive Plans (LTIPs).

To be fair, the UK Government itself has recognised the need to circumvent the dominance of the volume house-builders and their avaricious acquisition - and holding - of developable land by the introduction of the Self Build and Custom Housebuilding Act of 2015 and the Housing and Planning Act of of 2016. The former is intended to secure the release of publicly-owned land to self builders and to custom house-builders (for groups aiming to construct between 5 and 200 homes), whilst the latter, amongst other things, underpinned the support of this sector with substantial funding (and we’re talking several billion pounds here) accessible through the Homes and Communities Agency (HCA). Under these acts, every one of England’s 360+ local authorities is required to maintain not only a register of publicly-owned land within its boundaries that can be released for self or custom house-building but also a register of those individuals and groups seeking to construct new homes on this land.

Less free to commit large amounts of money in support of any similar initiative, the approach to self build and custom build taken by the Scottish Government is arguably aspirational rather than anything that might be regarded as a challenge to the hegemony of the country’s major house builders. Indeed, Scottish Government ambitions - and funding - to ensure more affordable homes are constructed is largely channelled via conventional routes, i.e. to the self-same builders that have singularly failed to date to deliver the numbers and types of homes the country needs. Yes, there are loan schemes for self building (mostly available in the Highlands) but these are clearly aimed at delivering very small numbers of new houses on individual plots, whilst the notion of custom build has been addressed quite differently from the way now motoring forward in large areas of England. In part this might be seen to be about the availability of funds, but it can also be interpreted as a lack of creative thinking as to how a substantial part of Scotland’s housing needs can be met through more direct community involvement: a bottom-up rather than a top-down approach.

For many architects, however, the idea of anything associated with self-build conjures up horror stories of whimsical projects ‘designed’ and constructed by their owners with the aid of family and friends, whilst the concept of custom build remains largely unfamiliar territory. Suffice to say, the latter is not simply self-build on steroids: there are now numerous specialist, nationwide companies in England engaged in helping hundreds of people to get the custom build new homes they want each year, most of which have a high level of architectural involvement. Practices such as HTA have taken a lead in this area and it is clearly a field of activity that offers real possibilities for the profession to affect not only the standards of housing provision but to deliver design solutions that are qualitatively distinct from the volume house-builders’ standard caveat emptor product.

Collective custom build takes a slightly different approach: whereas the individual self-builder has relatively few choices, a group of households can pool their knowledge and skills to overcome the political, legal and physical barriers to development. One such has grown out of the PEDAL group in Portobello, near Edinburgh and, led by architect John Kinsley, have produced an exemplar project in the town’s Bath Street for others to learn from and follow. Already a resident in the area, John was aware of the site and of its price, having previously been involved in a (failed) lottery application by PEDAL to develop it. An advertisement by the architect in Portobello Online led to the creation of a group of potential owner-occupiers and the formation of the Bath Street Collective Custom Build Ltd development company - a necessary exercise to enable the purchase of the land. The gap plot had formerly been occupied by two tenements and already had planning permission for a pastiche version of the same but, long empty, Edinburgh’s planning department was receptive to a design more empathetic to the street’s diverse architectural character.

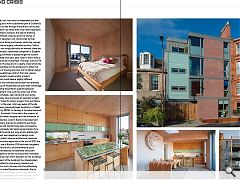

With a new permission approved at the end of 2015, the project started on site in Autumn 2016 and was completed in July 2017 - on the face of it, an extraordinarily quick process, but one preceded by considerable discussion between the prospective owners to ensure their individual requirements could be met within the plans for the building’s four apartments. Each of the building’s four shareholders was already committed to a low energy solution and, whilst not certified as such, the new block has effectively been constructed to meet Passivhaus standards. Key to delivering these - and to the build speed - has been the decision to use cross laminated timber for the walls, floors and roof construction. Produced by Egoin in the north of Spain, four lorry loads of panels arrived together with three joiners who, with the addition of a crane driver and a banksman, proceeded to erect the entire structure in nine days. Externally, the building is faced in stone with a timber screen at ground floor level permitting access to the rear, but internally the use of solid wood is entirely visible - the plan form of the new infill block is three bays wide and three bays deep, an ‘OXO’ layout in which the exposed timber walls (coated with flame retardant) of the central square contain the communal stair.

The effect on the senses is palpable: the fresh smell of the pine surfaces indicates immediately that this is no conventional tenement, an impression compounded by the realisation that the top of the stair provides further access to the still emerging communal roof garden. The top flat is owned and occupied by the architect and, in its elegant and spacious showcasing of the building’s conception and construction (the CLT is also exposed here, this time coated in a transparent white stain), it also represents something of a manifesto for Collective Custom Build: yes, each flat is bespoke in layout, but no developer has been involved in the design and construction; the residents have been able to buy at cost and have been involved as owners from day one; each is part of a collective responsibility for the building (thus eschewing the usual caveat emptor developer factor); and each has a commitment to the area and to involvement in the local community.

In the Bath Street Collective Custom Build, the architect has been central (indeed fundamental) to the project’s gestation; so much so that he has now structured his practice around this approach to the creation of new housing by guiding/leading other projects, providing key architectural services in the course of doing so. Certainly, much experience has been gained here, not least in the financial and legal issues arising in this still emerging form of procurement. The proof is in the pudding, however: genuinely affordable housing that has been built to last and which recognises that the dwell time in a home in which the owners have been directly involved in the design and construction is around three times as long as one bought via traditional routes. Other architects can learn much from this pioneering project, not least in how the profession might secure effective involvement in this growing sector - and drive an alternative view of how housing of real and enduring quality can be delivered in Scotland.

|

|

Read next: Park of Keir: Back and Forth

Read previous: New Town: Hot Date

Back to January 2018

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.