Architecture Fringe: Public Liability

23 Oct 2017

Renegade architect Lee Ivett applies insights gleaned from this year’s Architecture Fringe to issue a clarion call for change in public life, citing a dysfunctional bureacracy as the root ill of much mediocrity in planning, architecture and urban design.

As a profession we seem trapped in a cycle of trying to produce the ‘least worst’ instead of delivering what we know to be the best. Whilst there is undoubtedly a number of piss poor planners and abject architects unable to engage their brain, think critically, act creatively and produce quality work the failings lie within the administrative, organisational and political infrastructures rather than the people. This culture that is created through accepting and perpetuating the machinations of dysfunctional infrastructure leads to our best talent leaving Scotland and a deterioration in the quality of public life. During this year’s Architecture Fringe we sought to address these concerns with the delivery of two projects and a public debate that sought to identify how we have come to accept such mediocrity and to identify and promote new forms of civic architectural language. We aimed prove that the ideas, talent and energy required to create a visually and spatially ambitious public realm exists within Scotland and is deserving of an infrastructure that supports rather than denies its agency. Infra X was a unique collaboration between Edinburgh City Councils planning department and the Architecture Fringe that established a parasite research office within the department. In order to maintain balance and ensure no existing preconceptions on the part of our research team we engaged two visual artists with no previous experience of the planning system.

This move allowed a non-confrontational investigative discourse to emerge that allowed critical themes to emerge around the adequacy of the system rather than the quality of the people who operated within it. The work of Roos Dijkhuizen and Bobby Sayers supported by academic Ambrose Gillick found a department seeking to innovate in the way it organised itself, striving to identify and then deliver best practice. It was seeking to establish collaborative working groups that joined up roads, engineering, spatial design, economic development and all the different agencies and groups that had begun to work disparately rather than collaboratively. What the artists identified was how politics at both government and local level contrived and conspired to reduce the department’s ability to do the things it knew were right. This insight was articulated through an installation created by the artists at Civic House in Glasgow during the Architecture Fringe. A 3m high inflatable pound sign, a face with eyes that flickered uncontrollably with the relentless pages of planning policy and guidance and the barely audible sinister mutterings of the conversations happening behind closed doors at planning committee meetings visualised three fundamental issues.

1.From the very top of government and politics it has been determined that economic growth will be the single critical determining factor that will ultimately override all other considerations when determining development. It’s all about the money and it’s all about the numbers. Development therefore becomes weighted towards quantity rather than quality, risk aversion rather than innovation and value for money rather than value for people.

2.The system is confusing, impenetrable and indecipherable for those outwith it and often even those working within it. The lay person and the general public have their own agency diminished through thousands of pages of planning policy consisting of restrictive inane teams of text; guidance becomes interpreted as law and the language of policy isolates rather than engages. The system then seems to placate the masses through facile and patronising forms of face to face consultation that confuse entertainment with empowerment.

3. It’s not just at a national level where politicians and politics set the agenda and create the culture that architects and planners work within and which the public are forced to suffer. At a local level it is ultimately local councillors that become the determining factors in deciding what development happens, where it happens and in what form. The four/five year political cycle creates a culture of anxious restlessness and an aversion to risk. Politicians need to be seen to be delivering, change needs to be visual but uncontroversial.

Local politicians need to be able to own the investment that occurs on their watch and they need to have demonstrated a willingness to take on the causes of their voters. This alongside party politics creates a culture of short-termism, a predilection towards delivering the most the fastest and an acceptance of nimbyism. Architects submit their proposals to planners and then planners make their recommendations to councillors. These conversations happen in rooms along corridors behind closed doors. An incomprehensible discourse unrelated to quality and best practice informed by the whims and agendas of local politics. Democracy in action but at the expense of expertise. These three issues become expressed most identifiably within our civic infrastructure and public buildings. Within Scottish towns and cities our civic typologies are increasingly redundant as both function and as architecture: The market has been superseded by the shopping mall, the public baths have become the leisure centre, the town hall becomes the regional council office and the activity and architecture of democracy and public life becomes ever more distant from those it means to serve.

Our cities and our physical environments are increasingly designed to dictate behaviour, deny our natural human spirit and to lose confidence n our own agency and ability to affect the world around us. Civic architecture is not only increasingly peripheral and isolated it also tends towards the meek and banal as an architectural language. New schools look like out of town office buildings, massive white clad boxes devoid of natural light and sensory delight replace the ornate structures and visceral life of the town market and a twisting water slide becomes the only visual embellishment on the facades of our swimming baths and leisure centres. Extravagance is an expense, civic pride becomes an embarrassment not worthy of articulation through joyful design. Architecture becomes ever more disposable. This year’s Architecture Fringe delivered a riposte to this civic, architectural inertia with the exhibition ‘New Typologies’.

Emerging and established architects, landscape architects and designers from within Scotland were commissioned to re-imagine and propose a new language of civic. They created a new and progressive agenda for existing and historical typologies once fundamental to the public life of our towns and cities. This project was a reminder of how architecture can be utilised as a visual medium to communicate aspirational ideas about the way we do and the way we should live. The requirement to submit a single elevational or axonometric study and single model concentrated the minds of participants on the development of form and language rather than a pragmatic attempt at spatial planning.

The core group of Scotland based participants was supplemented by contibutions from London based Adam Nathaniel Furman and Porto based emerging practice Fala Atelier. The project therefore created a dialogue that extended beyond our own border and placed the work of Scottish practices in the context of a pan European discourse regarding the architecture of civic. Furmans now internationally published Democratic Monument proposed am exuberant mash-up of the post war local government modernism and cathedral gothic and Fala re-interpreted the arena as cultural venue without a physical audience. The public convenience became a vehicle for challenging gender stereotypes and sociability, the school became an adaptable machine for education that facilitated pupil centred learning through doing. The rising occurrence of debilitating mental health issues amongst common society was sensitively yet provocatively tackled by McGinlay Bell in the form of a huge arched civic room in the city, connecting the man made with the natural and range of spatial experiences from which to consider self. New Typologies asked why and demonstrated how. It presented possibilities that might not otherwise have been considered when constrained by the daily responsibilities of conventional practice and within a development system that is fearful of ideas and repulsed by the autonomy of the designer.

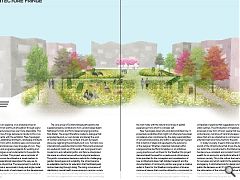

Whether a talented individual within a large practice like Mark Donaldson or an ambitious young practice such as Dress for the Weather this project demonstrated the need for a creative and critical space to be provided for the conception and consideration of new architectural ideas. Self-initiated research and the documentation of community centres was given a creative outlet in Dress for the Weathers composition of diverse communal spaces that could be utilised by a community to meet a variety of cultural and social needs and Donaldsons recent experience of designing public spaces in the city compelled a response that suggested a re-wilding of our urban centres. The introduction of meadows and wildlife proposed a new form of town square that questioned a contemporary narrative of hard landscaped, mixed use space that acts as a backdrop to commercial activity, mass entertainment and monuments to the past. In today’s society it seems that everything has its price and all of the infrastructure that drives the development of our public life is constructed to find that price. Architecture has become a compliant and complicit tool that creates wealth for an economic and political elite at the expense of common society.

This is the culture that we have created for ourselves and which restricts the potential of our impact and agency. A diminished role for design and architecture in public life demeans us all. It’s time to advocate and fight for the reformation of the critical infrastructure that supports the development of the built environment which in turn creates the back drop for public life.

|

|

Read next: St Andrew Square: Square Space

Read previous: Architecture Fringe: Open Source

Back to October 2017

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.