Cosmic Collisions: Star Struck

10 Jul 2017

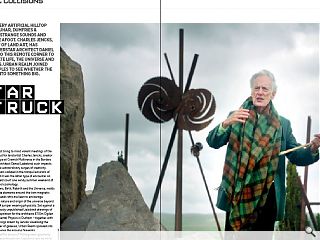

On a blustery artificial hilltop near Sanquhar, Dumfries & Galloway, strange sounds and visions are afoot. Charles Jencks, high priest of land art, has drawn superstar architect Daniel Liebskind to this remote corner to contemplate life, the universe and everything. Urban Realm joined their disciples to see whether the pair are onto something big.

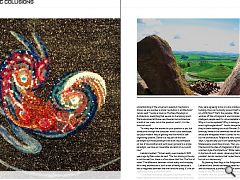

Collisions might first bring to mind violent meetings of the car crash variety but for land artist Charles Jencks, creator of the arts landscape at Crawick Multiverse in the Borders and idiosyncratic architect Daniel Liebskind, such impacts can also give rise to extraordinary surges of creativity. When these two stars collided in the tranquil environs of Sanquhar town hall it was the latter type of encounter on show as the pair held court one windy summer weekend of architecture, art and cosmology.Cosmic Collisions, Birth, Rebirth and the Universe, melds seemingly disparate elements around the twin magnetic poles of its figureheads who are keen to encourage questioning of the nature and origin of the universe beyond a niche audience of jumper wearing physicists. Set against a backdrop of previously unpublished Liebskind drawings of spiral galaxies – inspiration for the architects £11.5m Ogden Centre for Fundamental Physics in Durham – together with a selection of paintings drawn by Jencks visualising the collision and merger of galaxies, Urban Realm spiraled into the Borders to observe the ensuing fireworks.

Famed for his willful abuse of Pythagorean geometry and a disciple of deconstructivism Liebskind cast his mind back to Ancient Greece, marveling at the birth of science: “It was an interesting question written on the entrance of the Platonic Academy, ‘Let None But Geometers Enter Here’. What is geometry? It’s where we are, it’s how we measure. It’s not a speculation of who we are but of space. As I walked down that amazing, windy hill (at Crawick Multiverse) I thought about the fact that for less than a few centuries people have concentrated on the meaning of time rather than the meaning of space.”

Save for those trapped on the downward variety ‘everybody loves spirals’ continued Liebskind, adding. “I work that way. I go in circles only to get back to the same point, but not exactly the same point. It’s like a spiral. I thought about that as I designed The Ogden Centre for Fundamental Physics in Durham. If we take the spiral and apply it to a very modest office building what would we do?” Starting with a series of spirals rotating outward from the Cathedral Liebskind drafted a building plan bounded by those imaginary lines in three dimensions, prompting some ribbing from his old friend Jencks.

Liebskind explained: “Architecture seems very banal when we come from the cosmic because you’re thinking about the floor and simple things like the wall. How do you create something that’s interesting spatially? Charles asked me some weeks ago, can I draw a plan of the building? I was baffled. Every floor is different, it moves in an irregular spiral but it has a centre. All the projections, soffits and voids are used for terraces and extending the sense of community. I had so much fun designing this building, it is modest but has impetus geometrically and spatially and if you walk around the building several times I’m sure you won’t be able to draw a plan of it either - that’s what makes a building interesting!”

Where space exists time follows and as quantum physicists grapple with various flavours of the multiverse and infinity in a desperate bid to find a theory of everything Jencks prefers the meditative surrounds of the Borders to the laboratory in order to arrive at his own understanding of nature. Ruminating upon the wisdom of Woody Allen, who once said ‘eternity is a very long time, especially towards the end’, Jencks explained the genesis of his own Crawick Multiverse. “I wanted to do a series of analogies about collisions, before I started on the Multiverse project, that shows Andromeda and the Milky Way colliding in that incredible dance. I thought by and large collisions are catastrophic like a car or train collision, which are often used by scientists as an analogy for galaxies colliding. There’s a lot of destruction, no question. it’s bad for the dinosaurs and its bad for people. But cosmic collisions also produce beauty and billions of new stars, spiral galaxies when they meet have enormous fecundity.”

Asked whether he’d been on a collision course with Modernism Liebskind observed: There are tendencies in Modernism to be reductive, to reduce architecture to forms follows function per-se, which is not true. Everything is symbolic in some sense. The great architects of the Modernist period tried to communicate symbolic ideas, a glass or a white cube isn’t an ornament. Mies van der Rohe’s Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin, the glass building with a black temple building at its top, is the most violent building ever built. They cut the hill, levelled it and put this amazing thing on top of it. There’s nothing naturalistic about it. Architects have many different tendencies and the Holocaust followed by the bombing of Hiroshima has changed the tenor of humanity.

“It’s not a coincidence that architecture has always attracted authoritarian personalities, all dictators embrace architecture. From Rome to Germany to China and Donald Trump powerful builders who want to build new things have an authoritarian streak in them. That’s why I’m a great believer in democracy, it builds consensus in an open society. But democracies are vulnerable to alternative facts, is there such a thing as truth? I believe that there is. I think science is a community of reason, which prevails over fantasy and superstition. Science is a model which society can progress for the truth.”

Commenting on their enduring friendship Jencks joked: “I’ve known Daniel for 35 years, we haven’t always agreed. We do agree about that!” Liebskind added: “I read Charles’ book (Meaning in Architecture) in 1969, it’s still one of the classics in the field. Architecture is a cultural flow beyond being a technical field because every building communicates - even the most empty-headed building with a glass façade - because it tells you very, very rapidly that it has nothing to tell you! All you need as an architect is optimism, you don’t need mathematics, as Corbusier said when he was asked what is architecture? ‘You have to read a couple of books and travel, that’s all it is.’

Recalling their first non-physical contact, to Liebskind’s evident surprise, Jencks continued: “We had a meeting in hyperspace. We have had arguments but you were a great friend and I was a great friend of Hejduk but you wrote me a letter saying. ‘How dare you say that about John Hejduk’. I was trying to be ironically positive about John and you read it as an insult! We share a deep affinity, see the way we point at each other.”

Catching up with Jencks and Liebskind at the Merz Gallery in Sanquhar, where artwork from both designers is currently on show, Urban Realm asked whether the revolution in physics that has taken us from a classical understanding of the universe to quantum mechanics, shows we are overdue a similar revolution in architecture? Jencks said: “I wrote a book on The New Paradigm in Architecture, predicting that we are on the tipping point. We’ve absorbed all those new theories but architecture is built at our scale, not at the quantum world - it is the classical world.

“In many ways the answer to your question is yes, but slowly and through the computer, which is our telescope, our post-modern way of getting into the world of self-organising systems. Daniel is a key part of the new paradigm but these paradigms are built like palimpsest on top of one another and we’ll never go back to a single paradigm, we have an irreversible pluralism in our world now.”

Liebskind added: “Virtual reality was invented 2,500 years ago by Plato when he said, ‘The Sun shining in the sky is not the real Sun, there is a Sun above that Sun. The Sun of ideas.’ The difference between virtual reality and everyday life is why architecture is such a test of reality because it has to negotiate between the mind and the body. It’s not an intellectual thing, you’re born with it.

“I’ve always wondered why great scientists and even Avant-garde artists often live conventional lives. If you look at Picasso or Kandinsky their paintings are incredible but they were agreeing to live in a box inside an apartment building. How can humanity accept itself living in a box on a 30th floor? That’s the paradox. When I first tilted a window off the orthogonal it was considered a scandal, intelligent people said it’s not acceptable to tilt a window. Why is it not acceptable? Why is making a wall at not an exact right-angle taboo?” Jencks interjected: “Because they’ve been reading too much Pevsner! Susan Sontag famously wrote in the seventies that all these Avant-garde artists are renegades when it comes to music or cinema but not architecture. People are very conservative in many ways. Linguistically you’re still speaking the language that Shakespeare would have known. Then you have Prince Charles and the idea of integration of English culture around a certain style of architecture.” While Liebskind is relaxed in the face of such visions, observing that it’s simply ‘not possible’ Jencks cautions that ‘under fascism it’s possible - but not in a democracy.”

By planting their flags in the Enlightenment both Liebskind and Jencks are keen to reset our relationship with architecture, a profession which some might argue is losing its way. By reaching out and looking up they hope to elevate what can become lowest common denominator game - and are clearly having a smashing time in the process.

|

|

Read next: Barnton Quarry: Tunnel Vision

Read previous: Wavegarden: Swell Design

Back to July 2017

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.