Architectural Competitions: Luck of the Draw

24 Apr 2017

Today’s most successful practices always remember their first big break – often springing from a long-shot competition entry. Contrasting the experience of Bolles Wilson in Germany with home grown practices Mark Chalmers wonders whether todays young design-led practices can enjoy the same level playing field enjoyed by their more established peers.

If you raise the subject of competitions in Scotland, prepare to stand well back. The reaction of many architects is similar to whacking a hornet’s nest with a big stick, because the issue goes to the heart of how we win work.There are a few proven ways to get jobs: practices often start off with commissions from family and friends; a few carry out self-initiated projects. One-offs sometimes lead to repeat business, although framework agreements are more predictable. Then there are two sides of the cost-quality-time triangle: the fee bid tender (which comes down to cost(, and the design competition (which comes down to ideas).

The invited competition, where practices pre-qualify on the basis of their reputation and previous work, produces an instant shortlist, and for practices it reduces the amount of time devoted to speculative work. The downside is that small practices, young practices, and niche practices which would like to expand, may find it impossible to break into a new field.

The alternative is an open competition which anyone can enter, regardless of experience. In Scotland, the chances of building a career on winning an open competition are slim because the odds of winning may be 50:1, 100:1, or worse – yet there’s always hope. After all, wasn’t Jørn Utzon’s scheme for Sydney Opera House famously pulled out of the “rejects” pile by Eero Saarinen?

As I write, there are two high profile competitions running in Scotland – the Ross Pavilion in Princes Street Gardens, Edinburgh and Perth City Hall Regeneration. In a few months’ time we’ll discover who won them, and whether the judges followed a recent trend by awarding them to an “international” architect. The Riverside Museum in Glasgow, Scottish Parliament at Holyrood, and V&A Museum in Dundee all spring to mind.

Some put this down to a national failure of nerve, a shortage of talented practices in Scotland, or even the “cultural cringe” which we supposedly suffer from – but it’s inarguable that raw talent needs opportunity, and that’s seemingly in short supply here. Looking across the North Sea provides a different model for architectural competitions and building a practice.

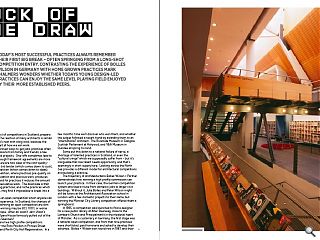

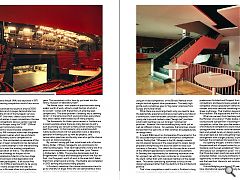

The trajectory of Architekturbüro Bolles-Wilson + Partner demonstrates how winning a high profile commission can launch your practice. In their case, the German competition system provided a route from domestic jobs to larger civic buildings. Without it, Julia Bolles and Peter Wilson might still be tutors at the Architectural Association school in London with a few domestic projects to their name, but winning the Münster City Library competition offered them a springboard.

In 1985, a competition was launched to find a designer for a new public library at Alter Steinweg, close to the Lamberti Church and Prinzipalmarkt in the medieval heart of Münster. As is customary in Germany, the first stage was a national open competition, and from that nine practices were shortlisted, paid honoraria and asked to develop their schemes. Bolles + Wilson won round two in 1987, and their award-winning building was completed at the end of 1993.

The competition system in continental Europe works in a quite different way to that in Britain, and James Stirling was another UK-based beneficiary of the German museum, gallery and library boom of the 1980’s, when he won the Stuttgart Staatsgallerie competition. As Peter Wilson of Bolles + Wilson said of his own practice, “How was it that we came to build buildings in many European countries? The answer is quite simple – the European competition system. This, our principal form of procurement, is also our principal form of research and we have accumulated over the years an archive of some two hundred zombies, designs that did not win and yet cannot be buried.”

During its first decade, Bolles + Wilson’s practice relied on entering and winning competitions to keep itself afloat. Even now, competitions are a major source of work, although Peter Wilson admitted that the success rate of converting competition wins into physical buildings is lower than you’d hope.

“As an office that relies on the competition as a principal mode of acquiring commission (we do not play golf and rashly declined an offer to join the Rotary) Bolles + Wilson works on the assumption that one in five competitions must be a win,” and in fact, “Once in a fit of scientific office control, [we] calculated that we needed to win at least one in five to keep our heads above water. Even then only 50% of first prizes get built.”

Despite Peter Wilson’s candour about the German system’s flaws, he considers it the least bad option when compared to the quality of architecture which emerges from framework agreements and fee bidding in other countries.

“Yet this is still a good system, one that delivers, or should deliver, architectural quality for many private institutions and all public buildings – schools, universities, government offices and so on – especially when, as is the case in Germany, 10% of participants must be young architects (a selection procedure that is now regulated by European law).”

A key difference between Germany and Scotland is that 10% quota – positive discrimination towards young architects, if you like – and that usually comes through state sponsorship and European diktat, rather than an act of altruism.

“In the European context, architectural competitions are the official procedure for selecting an architect for most public – and many private – buildings. Policed by Institute-sanctioned procedures, and increasingly by European competition selection processes, the system, in theory, operates Europe-wide. To Germany’s credit, it functions there with a political correctness and openness to entries from other European countries.”

Peter Wilson noted that this can lead to some competitions attracting over 200 entries, which lengthens the odds somewhat. Helpfully for architects, the German press actively monitors and analyses how the process works: the journal Wettbewerbe Aktuell (WA) was launched in 1971 with the aim of documenting competition results from across the country.

To date, WA has published the results of around 3000 architecture competitions and its pages demonstrate how things changed with the arrival of the European Services Directive (ESD) in 1997. Until then, clients could limit the geographical spread of entries in open competitions; the new rules stipulated that competitions above a certain size had to be advertised across Europe, using the “OJEC” (Official Journal of the European Community) notice.

While it was feared this would increase competition from foreign architects, WA’s analysis shows that the greater impact came from regional rivalries which saw architects from Berlin winning secondary school competitions in Munich, and vice versa. One unintended consequence of the ESD is that the number of open competitions has decreased significantly, as public clients attempt to limit the ballooning number of participants in even the smallest competitions.

Peter Wilson’s observation on that is, “The alternative to this enormous waste of energy on the part of the hopeful (and much-exploited architects) is the two-stage competition process involving an initial application and selection of ten or fifteen participants. It all sounds fine, even the requirement for [10%] of participants to be young architects of no track record, except that the rules laid down by the mandarins in Brussels often limit qualification to offices that have built a similar project in the past three years. The conundrum is this: how do you break into the library, museum or laboratory field?”

The former issue – with dozens of practices each doing weeks’ worth of work, all but a small fraction of which is to no avail – comes with the territory of entering open competitions. The latter problem – breaking into a seeming cartel – is the same one which young practices everywhere face, and it leaves them locked out of many projects.

The frameworks for Hubco procurement in Scotland are a recent example where there are many barriers to entry, such as proving you’ve built so many similar schemes in the past three years. In that scenario, only a practice which mainly builds schools will win education work, a laboratory specialist will always pick up new lab projects, and conservation practices are the only ones who get the chance to work on historic buildings.

By contrast, having got their initial break with a German library, Bolles + Wilson managed to win commissions for other building types. Their next high profile victory was first prize in the competition to design the New Luxor Theatre in Rotterdam, in 1996. The practice had already built the Bridgewatcher’s House and landscaping around the Kop van Zuid – but five years’ worth of work in the area didn’t debar them from entering and winning. The theatre was completed in 2001, earning the practice many plaudits.

In Scotland, meantime, the cultural commissions tend to go to a handful of larger firms who can demonstrate a track record in cultural buildings, and these are often procured using an invited competition, or the Brooks Method which weighs fee bids against other parameters. The really high profile work sometimes goes to “big name” practices from Europe and further afield.

While there are sound arguments why you need to have the appropriate experience and resources before you take on a commission, there have been consistent complaints from young start-ups and medium-sized “design-led” practices which both feel they lose out to larger “commercial” practices. However, the commissioning body could just as well set different criteria – for example, that practices should be less than five years old, or that schemes are judged purely on design merit.

A recent RIBA report on Comparative Procurement in the EU discussed the pros and cons of anonymous competition entries, finding that, “Whereas in the UK, design contests are not popular because of the requirement to assess design proposals anonymously this does not seem to raise such concerns in Germany. One reason for this may be as a result of the different approaches to construction procurement. In Germany the responsibility for obtaining insurance cover for a project lies with the main contractor or occasionally the client, rather than with individual members of the design team. This allows contracting authorities to focus on the designs proposed rather than the identity of the architectural practice.”

That’s how competitions used to work in Scotland, a long time ago. Looking through back issues of Urban Realm’s predecessor Architectural Prospect from the 1950’s, student competitions and beyond were judged anonymously. Each competitor chose a pseudonym rather than being allotted a number, and most selected something noble-sounding from Greek mythology. That tradition descended from the Beaux-Arts tradition, the esquisse and the Prix de Rome.

What can we learn from Germany today, particularly the Münster City Library? Public bodies in Scotland could procure a proportion of buildings through design competition, rather than pure fee tendering. The first stage of architectural competitions could include a 10% quota of young practices, entries could be assessed on an anonymous basis and judged purely on design quality. Where the winner has great ideas but lacks draughting firepower, a mentoring arrangement with a larger practice, or perhaps a split between the conceptual and executive roles might work.

As a parting thought, is there a relationship between the perceived lack of opportunities for young practices in Scotland, and the well-established “international” architects who seduce our competition juries? It’s worth considering that those European practices were established in a protected market. As young architects, they were given the opportunity to enter competitions as part of the 10% quota, and that was their chance to win commissions and gain experience.

If those fledgling practices of 20 years ago grew up to have international reputations, it’s only because they first got their break at home.

|

|

Read next: Kelvin Hall: Hallmark

Read previous: Practice Insight: Bennetts at Thirty

Back to April 2017

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.