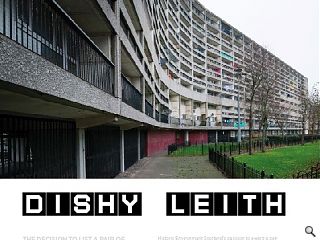

Banana Flats: Dishy Leith

24 Apr 2017

The decision to list a pair of Edinburgh tower blocks better known amongst cinema buffs than architecture anoraks has raised more than a few eyebrows. Urban Realm goes concrete spotting down in Leith to see why the banana flats are now a bigger a-lister than Ewan McGregor.

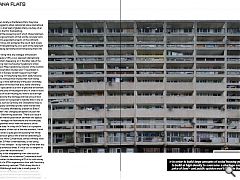

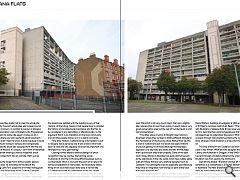

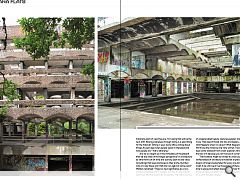

Historic Environment Scotland’s decision to award a pair of Leith public housing blocks with its highest listing category following a consultation with tenants has raised eyebrows amongst the public who have derided them as an ‘architectural cancer’ and ‘horrors’ - but what does the decision tell us about the reputation of post war architecture?Cables Wynd House and Linksview House are the 50th and 51st buildings respectively to be A-listed since 1945, elevating them to the status of the Forth Road Bridge and Commonwealth Pool. Familiar landmarks in their own right; particularly the playfully kinked profile of the former, which is known locally as the Banana Flats, they have however struggled to attain national let alone international fame save for a brief spell of global infamy courtesy of an appearance in the film Trainspotting.

Product of the pioneering spirit which infused planners, architects and governments of that era the concrete twins were inspired by equivalent projects on the continent, particularly France, and pioneered the use of deck access as a means of transplanting the civic spirit of the tenement streets then being demolished and transposing them into the sky.

Does the listing have any analogue with present day housing policy? Why is our approach diametrically opposed to what’s happening on in the other side of the world regarding high rise housing? Speaking to Urban Realm Professor Miles Glendinning, Director of the Scottish Centre for Conservation Studies said: “The problem is public opinion in Europe wouldn’t support such high-density building. In Hong Kong they don’t really have any alternative. The listing almost implies that multi-storey public housing is more definitively of the past. Ultimately, it’s a combination of the fact that land, home ownership and property speculation as a form of personal enrichment is forcing up the price of housing and land. In order to build large amounts of social housing you have to build at high density to overcome the shortage and high price of land and public opinion isn’t prepared to tolerate that. In one or two countries, such as Germany and Switzerland, they’ve kept up a properly controlled private rental market that doesn’t have the same affordability problem as Britain.”

Has St Peter’s has changed perceptions of post war architecture? Glendinning observed: “There is an issue in that there is an internal polarisation between two aspects of modernist heritage; the fashionable and the everyday building programmes which were the bedrock of the whole welfare state. In a way the St Peter’s is a symptom of the worst aspect of that cult of the elite architect. I think Watters’ new book is quite good at exposing that whole cult of the individual genius with a festival celebrating St Peter’s Cardross while Cumbernauld, almost infinitely more important than St Peter’s internationally, is now being allowed to fall into disrepair - to say nothing of the even less architecturally ambitious areas. It’s nice but is a tangent to the reality of post-war reconstruction.”

That reality is fast disappearing from cities such as Glasgow and Dundee, not to mention Cumbernauld itself which is committed to demolishing all 12 of its multi-storey blocks as part of a £70m regeneration drive with Sanctuary Scotland. Glendinning ventured: “Multi-storey blocks in inner areas of Edinburgh tend to be in small groups. It’s a modernist version of Geddes so it’s nice to have one or two close by which haven’t been knocked around too much, particularly Cableswynd. It’s a typically Edinburgh approach where they prefer not to clear the whole site. Edinburgh City Council’s whole idea was to keep council housing to a minimum, in contrast to Labour in Glasgow Edinburgh corporation was controlled by the Progressives who didn’t want to waste rate payer’s money so on a site like that where you had a perfectly good tenement. I imagine they didn’t want to knock it down because it would cost far too much money to rehouse and compensate people. Instead the block was designed to fit into the site with a curve at the end. It’s unique, I can’t think of anywhere else quite like that where you have a modernist block of that scale kinked to fit into an odd site, that’s just so Edinburgh.”

Observing the longer-term shifts in public opinion Glendinning casts his mind back to the fate of the neighbouring Leith Fort, subject to an ill-fated listing push in 1991 which was torpedoed by the Scottish Georgian Society, now The Architectural Heritage Society of Scotland (AHSS). Glendinning said: “It doesn’t mean that the tenants are saddled with the building or any of that rhetoric, all the listing means is that people have to consider the historic and architectural importance and that has to be considered in any demolition or alteration plan, so the argument that it is an imposition on the local community and will stop people doing x,y or z is clearly nonsense.

“The other Historic Scotland listing of Anniesland Court in Glasgow was a perverse one. It was a block which had been re-clad and was arguably not a terribly important one whereas this a very good listing.“

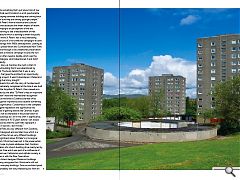

Looking further afield to other buildings for which recognition may be overdue Glendinning voices frustration at short term thinking afflicting places such as Cumbernauld, which is now past the point of no return for listing consideration in many areas. “An absolutely classic thing which could have been done were it not too late is Cumbernauld with its combination of low rise carpet area and tall blocks which are now being removed for no apparent reason apart from a skyline fashion”, Glendinning said. “Abronhill is still very much intact, that was a slightly later area and has its own town centre, it would make a very good conservation area but the rest of Cumbernauld is a bit too knocked about .

“The other place in terms of straight tower blocks is Aberdeen where they’ve taken a totally different attitude to the maintenance of the housing stock. Rather than say this is a lot of rubbish let’s pull it all down and spend millions of pounds getting rid of these dwellings the Aberdeen approach is to say these are assets and lets thriftily keep them up and look after them properly. Some of the best multi-storey blocks in Aberdeen are quite distinctive such as the slab blocks in the city centre which have rubbly gable walls and those that are very carefully designed such as Castlehill. The Gallowgate ones are especially good because they have an integrated multi-storey car park at the back that steps down the hill.”

Addressing the specific case of St Peter’s and whether brutalism was now on the long-road to public acceptance Diane Watters, buildings investigator at HES and author of St Peter’s, Cardross, told Urban Realm: “The thing with Brutalism is Gillespie Kidd & Coia never used that term to describe their work but people put that label in retrospectively to understand the period. What I try to do is assess through documentary evidence the contemporary story whereas I think Brutalism is a tag which has been put on.

The only architect from Scotland I can think of who used it was William Whitfield who designed the University Library and Hunterian in Glasgow. In the 1990s he said he went through a brutalist phase but the original term Brutalism was first used by the Smithson’s.”

Glendinning added: “Brutalism started off in terms of semantics as a catchphrase in a Reyner Banham book ‘Ethic or Aesthetic: The New Brutalism’. it started off as a trendy word by some intellectuals in London and was meant to be opposed to the original modern architecture of lots of blocks in open space but is now basically diluted and aestheticized into something that’s just about lots of raw concrete. The whole word brutalism is a bit questionable but if one’s just saying concrete buildings are coming back into fashion then sure they are among younger people.”

Looking at St Peter’s from a historical and cultural perspective Watters assesses the wider impact of recent preservation campaigns on perceptions of the era, saying: “We’re starting to see a reassessment of that post-war architecture which is starting to enter the public consciousness. I think St Peter’s has a very interesting preservation story but it’s not unlike the campaigns to save 19th century buildings from 1960s development. Looking at Cardross and its preservation and Cumbernauld New Town, Cardross has gone through a very traditional preservation process. There was a massive campaign to save the ruin and conservation often needs a baddie which was the Archdiocese of Glasgow who’d abandoned it and didn’t appreciate its beauty.

“It’s a tragic story, at Cardross the myth is that it’s an unappreciated building that it was abandoned by a philistine client. The book details that it was a very ambitious client that gave the architects an opportunity and a very costly project. It wasn’t abandoned, it failed and it’s about setting that story straight.”

Watters contrasts this with the story of Cumbernauld which was internationally recognised at the time it was built - a far cry from the forgotten St Peter’s, then viewed as a ‘provincial’ project by the elite. “St Peter’s was an important building but it didn’t have the international recognition that Cumbernauld had and so Cardross started off as something of regional importance and became something of international significance. Cumbernauld is the complete opposite. Its original reputation and significance has been lost, instead of getting awards like Cardross it gets anti-awards. I’m not as interested in the preservation or listing of these buildings as I am in the shift in significance. I try to keep a distance of 10-12 years before I can assess something. It could be that the Leith flats represent a significant shift in opinion, I don’t know.”

“The Banana Flats are very different from Cardross, they’re architect designed and are listed now which is a positive thing but they’re two very different buildings. What I think is significant about St Peter’s is its original significance which I think has been lost in the preservation campaign and I hope my book addresses that. Cardross was the culmination of a church building drive mainly led by Gillepsie Kidd and Coia and it was part of a confluence of confidence in post war Catholicism and catholic society in Scotland that ties in with the New Town ethos.

“Bespoke architect-designed Modernist buildings are definitely being recognized but I think we’re still not recognizing the everyday buildings. From an architect point of view they’re probably not very interesting but from an historians point of view they are. I’m hoping that will be the next shift. Raising awareness through listing is a good thing for the historian. Sitting in your dusty office writing about things 20 years ago when people weren’t interested and now people are – that’s satisfying.“

Are we so caught up in the immediacy of the present that we lose track of the longer perspective? In architecture as other forms of art time and scarcity seem to add value to buildings that were dismissed in their prime. But then who is to say these won’t fall into ruin again at some point? Watters remarked: “There’s a new significance as a ruin, a piece of heritage and a modern icon but it’s the original sentiment that the book tries to address. The myth, the loss, of unappreciated beauty captures people’s imagination more. That idea of threat and loss and beauty with Cardross what happens when it is saved? What happens to that idea? Will it lose the romance only time will tell. There has already been some kickback from urban explorers who are feeling the loss of it because you can’t access it currently.”

That kickback might be limited to urban explorers and a rarified breed of architectural historian at present but with dozens of towers being felled for every one listed how long might it be until we all rue the passing of these giants? If the time to pause and reflect doesn’t come now the passing of these background giants will surely consternate many more of us over the years ahead.

|

|

Read next: Practice Insight: Bennetts at Thirty

Read previous: Architectural Competitions: A Mugs Game

Back to April 2017

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.