Housing Crisis: Home Front

21 Apr 2017

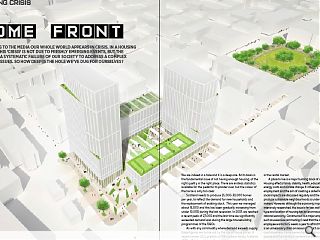

According to the media our whole world appears in crisis. In a housing context this ‘crisis’ is not due to freshly emerging events, but the result of a systematic failure of our society to address a complex series of issues. So how deep is the hole we’ve dug for ourselves?

Scotland needs to produce 25,000-30,000 homes per year, to reflect the demand for new households and the replacement of existing stock. This year we managed about 16,000 and this has been gradually increasing from under 10,000 during the last recession. In 2005 we reached a recent peak of 27,000 and the last time we significantly exceeded demand was during the large housebuilding programmes of the 1960s.

As with any commodity where demand exceeds supply these figures are borne out by the rise of house prices. A recent review (JLL) predicts a 10% increase across Scotland (23% in Edinburgh) over the next five years with similar rises in the rental market.

A place to live is a major building block of our society. Housing effects family stability, health, education, crime, energy costs and climate change. It influences flexibility of employment and the aim of creating a skilled workforce. The social impacts are discussed regularly and the necessity to produce sustainable neighbourhoods is understood by policy makers. However, although the economic impacts have been intensively researched, the issue is far less well promoted. The type and location of housing has an enormous impact on the national economy. Construction is a major employer and issues such as excessive commuting (I read that the average UK employee works for 5 weeks a year to afford their travel costs) is an unnecessary drain on resources which could be better used elsewhere. Home ownership is a personal goal for many people and the inability to achieve it at a reasonable cost must have a negative effect on the nation’s sense of incentive.

These shortages are most acutely felt by the young, who are trying to find somewhere to buy, by the old trying to downsize to more appropriate accommodation and by the poor who cannot access quality accommodation in their area. Perhaps one of the problems is that the status quo seems to work reasonably well for a great many people, who have a house, have enjoyed historically low mortgage rates and can probably look forward to some “Equity Release” in later life. This is bound to reduce the political drive for change.

The issues are also geographically distributed through continued migration to successful cities and to the shortage of permanent accommodation in areas where the tourist industry is strong. The housing shortfall also has an impact on our upgrading of housing stock, much of which is in need for major renovation, but requires resource in addition to that aimed at creating an adequate supply.

There is no doubt that the Scottish Government is trying to address the issue with various policy shifts aimed at stimulating production, providing support for first time buyers, promoting affordable housing and reviewing the planning system. However this is a long term issue and the effectiveness of many of these policies still remains to be seen.

There is controversy over the Land and Buildings Transaction Tax which is negatively effecting inward investment at the higher ends of the housing market. This issue is about more than expensive private houses, as much of the institutional private investment emanates from outside Scotland and the worry of this being “the thin end of the wedge” is uppermost in many investors’ minds. Having said that, there is a tendency for the UK press to negatively emphasise any tax change in Scotland, only to ignore it when something similar happens in England soon afterwards. However, we need to be very careful on how we project ourselves to the international investment world.

One of the big talking points at present is the rise of the Private Rented Sector with renting becoming a more prevalent housing choice. Home ownership in Scotland has declined (approx. 70% - 60%) and private renting has increased (approx. 5-15%) over the last 20 years, bringing us more in line with the rest of Europe. Currently this model is mainly being delivered in London and to some extent Manchester, with Scotland only having around 5% of the UK total PRS production.

There still seems to be a strong demand for student housing in certain areas as education increases and institutions provide more organised accommodation for their younger students. This housing type is often a target of opposition by neighbourhood groups and we need to recognise that it is a major component in inner city regeneration, as it operates at high density, does not require car parking, fits effectively over shops and provides accommodation for the tourism industry. As such, I cannot see any fundamental problems with it other than avoiding over provision in some areas.

This problem is not insurmountable, we can address it, we just need effort. We need to be ambitious and confident, seeing it as a wonderful chance to make our country a better place. We are lagging far behind other northern European countries in most aspects of caring for our physical environment and the housing situation is just a part of this. Denmark, Sweden, Holland and Finland (I have excluded Norway due to their vast oil wealth) all do this, so we can as well.

So moving forward, here is my personal bucket list of issues which we need to consider and change. These are wide, certainly not something that architects and designers can achieve on their own, but we can help drive agendas forward:

1. We need civic leadership. One thing that is clear in visiting our Northern European neighbours is the degree of civic leadership which underpins the development of their towns and cities. In most of these countries the city takes the lead, defines requirements, coordinates agencies and provides the infrastructure, with the role of the developer being to deliver a more defined product. In the UK, civic leadership is far weaker and much more of the fundamental decision making is passed to the private sector. While this suits certain organisations, it tends to put emphasis on land acquisition rather than product delivery. Providing better civic input would reduce planning disputes, mitigate investor risk and cut delivery times. I feel many housing developers would sincerely welcome such a move. In addition, it would also increase public respect for the process of expanding our towns and cities.

2. Cities need a clear vision. The current process is divisive and combative, a tussle between developers and community groups which leads to decisions being made on short term political grounds. The key issue is that no-one is articulating a comprehensive vision of what their town or city is working towards in the long term. Any “visions” which do exist are not detailed and planners can only provide some strategic or local plan, a map with some coloured zones on it, which is valid for 10 years maximum.

Central to this is a properly skilled and resourced planning system. Planning has become a highly maligned discipline and is regarded by many as simply an impediment to progress, while others regard it as too weak and over influenced by developers and politicians.

But a “planned future” must be much better than an “unplanned one” - so we must achieve a system where planners are trusted to plan. They have become reactive, reduced to trying to improve the worst other than to lead the best. All our towns and cities need proper active planning. This means good long term information on demands and requirements and well considered design briefs for sites prior to marketing. When these excellent and considered plans are produced and agreed, they must then be defended and not seen as simply a starting point for negotiation.

3. Co-ordinated infrastructure is a must. Infrastructure in its broadest sense, schools and medical facilities, roads, drainage, and district heating networks, are a major impediment to most large projects and rarely can a single development organisation address them adequately. We need a centralised body controlling many of these aspects, and that body needs to be in place for a long period of time. We don’t seem to have had that consistency since the era of the New Town Development Corporations and we have seen organisations like Urban Regeneration Companies grow and then get disbanded. This consent change of approach is exacerbating an already difficult problem and we need to agree a method and then stick to it.

4. We need to work together. This is said so many times. Lots of people and lots of organisations are trying to address this question but it is enormously “sectoral” with people each looking at their own specific agendas and preaching to their own band of converts. If you attend an architectural conference, you will find very few developers in the audience. Conversely, property industry ones are mainly agents and investors, with not a planner or a politician in sight.

It needs a “big player”, such as government, city regions or perhaps major councils to try to bring these sectors together. Much is made of integrating the public and private sectors, but a good start would be the public sector integrating itself. Delivering housing involves funding and planning, but also organisations like Scottish Water and SEPA and currently they do not seem to be relate as they should.

It is vital that a new relationship is formed between the needs of society and the volume house builders. They are the main delivery vehicle for housing in Scotland and right now the situation seems to work for neither party. We need to remove frustrations within the system that inhibit progress, we also need to look at the type of environment we want and support those developers willing to provide it.

Having a diversity of scale of building provider is important as currently the majority UK houses are produced by a few very large PLC’s) and the system currently mitigates against medium and smaller sized companies. Yet they are vital, as they provide local employment, diversity and build the infill sites which provide urban continuity, but there is a conflict in the housing industry between stated government support for SME businesses and the availability of development finance.

In these public /private sector discussions, there is usually little reference to the civic sector, but I think they are a vital and untapped resource (I am a past chair of the Scottish Civic Trust). Recent planning reform has focussed on increasing consultation and public input into the development process and civic groups could form the core of this input. Development is complex and unless we have structured and well informed groups within communities for planners and developers to consult with, then we end up with narrowly focused “protest group” scenario and a cycle of conflict which delays projects, costs everyone lots of money and depresses communities.

5. We need a consistent land supply. This is fundamental to meeting housing targets and appears to be failing in both a planning and economic sense. We seem to be bogged down in an interminable argument over greenbelt versus brownfield, which quickly becomes mired in local politics and landowner interests. The reality is that we need both approaches. The principle of “brownfield first” is one which most people agree with, as it supports existing neighbourhoods and makes use of existing facilities and infrastructure. However, remedial and decontamination costs often push budgets beyond the limits of feasibility. This needs to be recognised in a wider economic sense, in that there is very little alternative to public investment in the case of many such sites.

The whole green belt principle needs re-examination if our towns and cities are to have an adequate land supply for the future. Much greenbelt land is under used and much better use could be made of it. The danger of not providing this land is that we simply export the issue of house building out to peripheral towns, bring with a consequential issue of transport and commuting (you can see this very strongly around Edinburgh). Sometimes, this might be the right approach but currently it is happening on a piece meal and unplanned basis.

The financial mechanics of land supply is a key element in the affordability of housing, with land costs equalling the construction costs in some projects. If we want to create less expensive housing, then the cost of land is an obvious target. Much of this land is publically owned and I am told that we value public land in the UK at a higher rate than seems to be the case in many northern European countries. This effects mechanisms such as Compulsory Purchase and is an area which perhaps there needs to be a great deal more transparent explanation and clear thinking done.

6. Quality is Vital: We need to be creating places that attract and inspire people who live in them. Although architectural design and construction quality are important, this is fundamentally about quality of the lifestyle provided by new housing developments and needs to be considered on a neighbourhood basis. We need neighbourhoods which allow for access to outdoor recreation, the ability to walk to primary schools and shops and have good public transport connections.

One of the biggest challenges to quality is that of scale and its consequential impact on diversity. If we are serious about a “sustainable development” we must recognise that one of the fundamental tenets of sustainability is diversity and this applies to towns and cities as much as it applies to oceans and forests.

We have a challenge to deliver big numbers and that means large scale delivery mechanisms. Already the bulk of our houses are produced by a few large providers and organisations like housing associations are grouping into larger and larger units. The Current Farmer Review of the UK Construction Labour Market concluded that we are running out of building workers, so increasing off-site fabrication is vital, but this could just lead to more standardisation of product. However this is not an inevitable outcome, many new organisational methods and production technologies actually support individualisation and diversity of products and the choice of direction lies firmly with us.

The smart house is already with us and connectivity is simply going to increase, but what will the driverless car mean for parking requirements and housing layouts? Are future energy systems going to be centralised, as the current district heating model, or are we looking at a much more dispersed individualistic future? Will localised food production become more the norm and will e-commerce distribution centres be a new local centre component?

Too often the architectural world retreats into fashion, preferring debates on style and the promotion of “leading edge” one off houses. If we want to help this critical issue we need to grasp the big issues.

So, as a suggestion, how about a drive to have our government meaningfully reform the wasteful and massively inefficient construction procurement process and use the savings to create a modern and effective planning system - and an infrastructure delivery agency? I reckon that would go a long way to addressing the housing crisis – and there might even be a few votes in it too!

|

|

Read next: Superior Interiors

Read previous: Alexander Thomson: Break the Mould

Back to April 2017

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.