Japan: Modular Man

17 Oct 2016

Smith Scott Mullan director Eugene Mullan peers behind the cherry blossom to offer his insight into the Japanese approach to off-site timber construction and whether this modular model offers a potential solution to challenges at home.

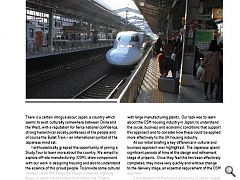

I enthusiastically grasped the opportunity of joining a Study Tour to learn more about the country. We aimed to explore off-site manufacturing (OSM), draw comparisons with our work in designing housing and also to understand the essence of this proud people. To provide some cultural context I read Will Ferguson’s book Hokkaido Highway Blues, in which he describes hitch hiking the “Cherry Blossom Front” from Cape Sata to Cape Soya. I have always loved Cherry trees and the way they flamboyantly mark the start of the spring, reflected in a Japanese phrase “Genki” which means healthy, energetic and filled with life.

The Learning Journey was organised by Scottish Development International. Attended by an expert group of professionals, academics, housing developers, lawyers, architects and manufacturers thrown together for an intensive week of lectures, site visits, factory tours and late night debates over a few glasses of whisky, not to mention the occasional karaoke session. The journey took us from Tokyo to Osaka and back, through a number of small towns with large manufacturing plants. Our task was to learn about the OSM housing industry in Japan, to understand the social, business and economic conditions that support this approach and to consider how these could be applied more effectively to the UK housing industry.

At our initial briefing a key difference in cultural and business approach was highlighted. The Japanese spend significant periods of time at the design and refinement stage of projects. Once they feel this has been effectively completed, they move very quickly and without change to the delivery stage, an essential requirement of the OSM approach.

Consideration of the housing industry in Japan reveals a very different design and development context. There is an enthusiasm for new houses, contemporary design and the latest technical solutions. The value rests in the land, rather than in the building, so there is a “scrap and re-build” approach to the houses (typically on a 25-30 year cycle) and hence houses devalue with age. Only 15% of house purchasers buy a second hand house (compared to 95% in the UK). There are four large companies SxL, Sekisui House, Sekisui Heim and Daiwa which provide a mass produced, customised, off-site manufactured product to the housing market.

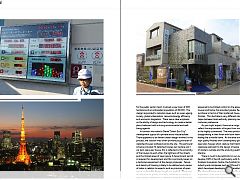

These companies have had the confidence and long term investment in the housing market which has enabled them to support extensive research and create large manufacturing plants, which employ thousands of people, typically producing over 1,500 houses per year. Not surprisingly, they protect their Intellectual Property robustly and we were actively chaperoned (without our cameras) when visiting the factories. The production lines, the sense of organisation, the efficiency and the drama of eight metre high robot arms manhandling section of rooms around on their 24 hour shifts was impressive. This customised prefabrication system can assemble a new house in eight hours, ready for delivery. The factories themselves actively manage their energy usage with solar panels on all available roofs and minute by minute monitoring of energy generation against energy used. The Japanese attention to detail is reflected in the inspection regime, primarily carried out by women, because they are apparently much more demanding in this respect! Additionally the customer service ethos is characterised by the daily display of the names and pictures of the people whose houses are being manufactured, making that all important connection between the customer and factory production.

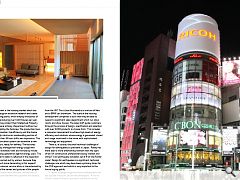

So how does the customer experience in Japan vary from the UK? This is best illustrated as a mixture of Ikea and a BMW car showroom. The scale of the housing development companies is such that they are able to support a significant sales department which run show rooms and show houses. The sales staff guide customers through the process of design, specification and selection with over 3,000 products to choose from. This includes a consumer requirement to achieve high levels of energy efficiency and solutions where energy is generated, stored and usage monitored in the home with sophisticated technology and equipment.

There is, of course, the small technical challenge of design for earthquakes so prevalent in Japan. Rarely has there been a more entertaining moment than the sight of ten UK construction professionals being “shaken and stirred” in an earthquake simulator, set at 9 on the Richter scale! Design for earthquakes is a significant, technical challenge, one which may have been a primary driver for the OSM approach and which is very important to the house buying public.

In Japan, strategic neighbourhood developments are led by both the public sector and developers. A visit to Nikken Sekkei Architects provided information on the Kashiwa-No-Ha Smart City project. This masterplan, for the public sector client, involved a new town of 300 hectares and an anticipated population of 26,000. The design responded to national issues such as super ageing society, global urbanisation, resource/energy efficiency and economic stagnation. There was a clear emphasis on the ability of design and technology to create a better place, balanced with a strong environmental and well-being agenda.

In contrast we visited a Diawa “Smart Eco City” development typical of a private sector house builder. There appeared to be limited urban design involved in this process, the solution was driven primarily by provision of detached houses scattered across the site. This particular scheme provided 75 detached houses per hectare and 1 car park space per house, this is reflected in the proximity of the houses to each other, the tightness of the streets and the limited areas of open space. A Government permit is required for development and this is primarily based on a technical assessment of the design proposals. Tenure and density of housing is likely to be defined and a series of ratios in relation to aspects such as provision of open space, sustainable design targets are applied. There was no reference to quality of streets, hierarchy or variety of open spaces, landmarks or character areas and the result, in this case, was a very poor quality placemaking. There appeared to be limited control on the appearance of the houses and hence this provided greater flexibility for the purchaser in terms of their preferred house design and finishes. This illustrates a very different relationship in Japan between local authority planning requirements and customer preference.

As you might expect, there are a range of houses to reflect the requirements of buyers from mass produced, to the highly customised. The mass produced were disappointing in their finish with both internal and external feeling like a mobile home. At the other extreme were high quality finishes with contemporary glass and timber, open plan houses which capture that traditional famous Japanese approach to the design of space, relationship of inside to outside and the enduring quality of light and shadow.

There is much to be optimistic in our capability to develop OSM in the UK, particularly with the Construction Scotland Innovation Centre, the Scottish timber frame industry and companies such as CCG and Stewart Milne which have been developing their manufacturing capacity. We returned home very impressed by the learning experience, conscious of the challenges posed and very enthusiastic about the opportunities to develop this aspect of our industry. Stay Genki!

|

|

Read next: Stirling: Six Pack

Read previous: Public procurement: Bang goes your buck

Back to October 2016

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.