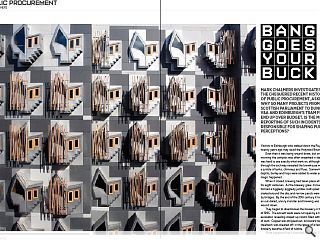

Public procurement: Bang goes your buck

17 Oct 2016

Mark Chalmers investigates the chequered recent history of public procurement, asking why so many projects from the Scottish Parliament to Dundee’s V&A and Edinburgh’s tram fiasco end up over budget. Is the media’s reporting of such incidents responsible for shaping public perceptions?

Visitors to Edinburgh who walked down the Royal Mile twenty years ago may recall the Holyrood Brewery.Even then it was being wound down, but on a winter’s morning the complex was often wreathed in steam. It was hard to see exactly what went on, although a glance through the archway revealed the brewhouse wrapped in a jumble of tanks, chimneys and flues. Somewhere in the depths, barley and hops were added to water and then magic happened.

When it closed, brewing had taken place at Holyrood for eight centuries. As the brewery grew, its buildings formed a higgledy-piggledy jumble: roofs piled up, ducts snaked around the site, and narrow pends were overflown by bridges. By the end of the 20th century it had become an out-dated, unruly monster and brewing was gradually wound down.

They began to disembowel the brewery in the summer of 1995. The ancient walls were cut open by a hydraulic excavator, revealing closed-up rooms filled with decades of dust. Copper was stripped out, brickwork toppled and steelwork was sheared off: in the space of a few weeks, the brewery became a field of rubble.

What happened next surprised everyone. For several years the site had been earmarked for the Younger Universe – a giant biome whose concept was similar to the Eden Project. After much effort and design work, that project was stillborn. In its place, the site was adopted by the new Scottish Parliament building.

Holyrood became the newspaper story of the decade but instead of lauding the building’s architecture, the headlines screamed: Scandal! Disaster! Travesty!

The architects were self-indulgent, they claimed: the project managers inept, the procurement process flawed and the budget out of control. A typical reaction came from Andrew Bolger of the Financial Times, “Although the controversial building by Enric Miralles, the Catalan architect, has subsequently won numerous plaudits for its original design, the fact that it had cost £430m by the time it opened in 2004 - more than 10 times initial estimates - has never been forgotten.”

Yet he doesn’t go on to explain why. There is a history of public projects going spectacularly wrong, if “wrong” means exceeding their original budget by an order of magnitude and ending up several years late. Sometimes the quality suffers, too. The reasons why that happens are rarely explained to the public, but they form an opinion, regardless.

At the top of the page in your project management textbook is a little triangle; the three vertices are named Cost, Time and Quality. We’re told you can’t have all three, and it turns out that you’ll be doing well to achieve two of them simultaneously. At Holyrood, it seems that quality was achieved at the expense of cost and time.

No-one knows what a building will actually cost until it’s fully designed, and a fixed tender is offered to construct it. The reason we can accurately state the cost of a toaster or laptop is because millions of identical units are churned out every month. Not so with Scottish Parliaments. No-one explains this to newspaper journalists; or if they do, the explanation goes unheeded.

The project began in earnest in 1997, and the first figures revealed were a £40m budget, for a notional building of 11,500 m2 on a site not yet chosen. As Lord Fraser highlighted several years later, “…the £40 million figure could never have been a realistic estimate for anything other than most basic of new Parliament buildings. However, what can be stated clearly is that at the time £40 million was included in the White Paper, there was no clear understanding whether that was a total cost including professional fees or only a construction cost.”

The mythical figure of £40m came to haunt the project.

In December 1997, the upward spiral began. The construction cost for the Holyrood site was stated as £49.5 million, and an OJEC notice was issued with a gross floor area of 17,000 m2. A few months later, EMBT/RMJM’s winning competition entry was costed at £62.60 million for 27,610 m2. By February 2000, after much design development, the construction cost was estimated at between £100 to £150 million.

In March 2000, Enric Miralles fell ill, perhaps due in part to the strain of the Scottish Parliament project and the machinations of his client.

Over the previous eighteen months that client had evolved into the Scottish Parliament Corporate Body: they ripped up the brief and started again. The number of staff requiring accommodation rose from 400 to over 1000; extra facilities were added including broadcast studios; the debating chamber was famously redesigned. In all, the changes trebled the original floorplate to 33,000 m2.

By the time the Holyrood Inquiry under Lord Fraser opened in June 2003, the final account estimate stood at £373.9 million. Fraser drew the conclusions that costs increased because the client drove through major changes, but using the construction management route was without doubt the “biggest single error”. Eventually it was complete: but the final figure was over £400m, and the building was three years late.

Arguably there were a few more contributory factors. Unless a project has a controlling mind from start to finish, it rarely goes well. There was a lack of continuity at the Parliament, because both the architect Enric Miralles and the project’s political champion Donald Dewar died during construction; over the course of time, two project managers resigned in frustration.

You need to match the professional team to the desired result. Despite claiming to want a modest building to house MSP’s, Donald Dewar selected an architect known for his wilfully experimental architecture. Likewise, full and accurate briefing is vital, but the initial brief and specifications for Holyrood were inadequate and underestimated floorspace, accommodation and facilities.

Arguably for something as complex as a Parliament, you need an expert client as well as expert professionals. If you have politicians and advisors with little experience of commissioning a one-off, high profile, high budget project funded using public money … why put them in charge of commissioning a one-off, high profile, high budget project funded using public money?

Perhaps the team in Edinburgh could have learned something from Australian experience.

Everyone thinks they know the story of Jørn Utzon’s Sydney Opera House. Budgeted at $AU7m, the Opera House ended up costing more than $AU100m, and was almost a decade late. Utzon’s competition-winning design was essentially a series of concept sketches, a “magnificent doodle”. However, the state government insisted that construction work start quickly, before Utzon had developed final designs for many aspects of the building.

The Opera House was Joe Cahill’s pet project, but by the time Utzon was appointed the New South Wales premier was seriously ill, and reportedly instructed his people to, “Go down to Bennelong Point and make such progress that no-one who succeeds me can stop this thing going through to completion.” That ulterior motive almost proved fatal for the Opera House.

Construction began quickly, but it turned out that the podium columns weren’t strong enough to support the roof, and these had to be rebuilt while the roof shells themselves were redesigned several times. The project’s engineers rode to the rescue, and in some ways the Opera House was the making of Ove Arup, whilst becoming the unmaking of Jørn Utzon.

A breakdown in relations between Utzon and the New South Wales government finally led the architect to resign his commission – forced out by Minister for Public Works, Davis Hughes, who held him personally responsible for the problems. Miralles didn’t live to see the Parliament completed, whereas Utzon was exiled from the Opera House.

The Opera House’s problems began right at the start of the project. As with the £40m figure for the Scottish Parliament, in Sydney, the $AU7m figure was a political budget. The need to make progress at all costs was counter-productive: in the long-run, the building would have been completed more quickly had the client waited until the design was fully formed and all the technical challenges surmounted.

The Opera House has been pored over many times in the search for lessons learned, but perhaps the most acute analysis came from the Danish economic geographer Bent Flyvbjerg, who incidentally works at Aalborg University, the same place which made Utzon an honorary professor. According to Flyvbjerg, the real cause of projects running out of control is psychological, rather than technical. He identified a condition peculiar to public officials involved with major projects: the desire to get projects off the ground creates a delusional kind of optimism:

“In the grip of the planning fallacy, planners and project promoters make decisions based on delusional optimism rather than on a rational weighting of gains, losses, and probabilities. They over-estimate benefits and underestimate costs. They involuntarily spin scenarios of success and overlook the potential for mistakes and miscalculations. Again, this results in the pursuit of ventures that are unlikely to come in on budget or on time, or to deliver the promised benefits.”

He adds that this kind of spinning is largely driven by politics: “Where there is political pressure, there is misrepresentation and lying.” So major public projects are set up to fail. Similarly, the decision which politicians like Joe Cahill and Donald Dewar make are coloured by leaving a legacy; what Flyvbjerg calls a “monument complex”.

There are plenty other examples of public procurement going awry; the Scottish Parliament and the Sydney Opera House are just the most infamous. There’s the new Berlin Brandenburg airport, delayed by technical problems and likely to be six years late with a total cost of €5.4bn against an initial budget of €2.9bn. Or perhaps the Edinburgh Trams project, which was originally costed at £375 million in 2003, but had a final cost over £1 billion when it was completed in 2014, three years late.

However, to balance the perception of failure, it’s worth noting that the Pompidou Centre, Empire State Building and Eiffel Tower came in on budget, and perhaps surprisingly, it turns out that Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Bilbao was also delivered on time and on budget. Despite the seemingly chaotic sense of architectural order in his buildings, Gehry’s delivery of the projects is driven by process.

Gehry explains, “One of the great failings in these public projects is public clients, that is, clients that are involved with politics and business interests. These clients often eliminate good architecture because they don’t understand it, and they’re wary of it, and they’re unable to imagine that somebody who looks like an artist could possibly be responsible.”

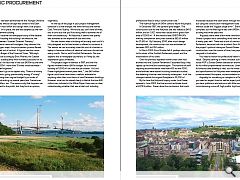

The so-called “Bilbao Effect”, creating a cultural outstation which helps to regenerate a post-industrial city seems like a form of “cargo cult” economics, but nonetheless it appears to work. It relies on creating a high profile building which becomes an emblem, and the method has since been applied to the Tate at Liverpool, the Louvre at Lens in France, and currently the new V&A museum in Dundee.

Gehry is wary of clients who want to eliminate the architect-artist from this process because, “That is the worst thing that could happen. It requires the organisation of the artist to prevail so that the end product is as close as possible to the object of desire that both the client and architect have come to agree on.”

He also feels that, “Building costs are not as controllable as people make them sound. … The only way to control these things is not to proceed with the building until you have all the drawings complete, you have everything the way you want it, you’ve done your due diligence on cost analysis.”

That is of course predicated on the initial cost being realistic in the first place and as we’ve seen at the Opera House and the Parliament, there are many reasons why it may not be.

Bent Flyvbjerg’s solution is radical: “The key principle is that the cost of making a wrong forecast should fall on those making the forecast.” That’s a sobering thought: the politicians, civil servants and project managers who call the costs should make good any shortfall. Perhaps fewer high profile projects would “fail” – or perhaps fewer would be built in the first place – but the terms of that “failure” are open to a different analysis.

Today the Opera House is wildly successful and attracts vast amounts of visitors to Sydney. Perhaps it’s the world’s most famous building. It has paid for itself many times over, in good public relations, goodwill, hotel bookings and so on – perhaps Joe Cahill and Jørn Utzon anticipated this, but Davis Hughes clearly had other things on his mind.

Sometimes the short-term anguish of a procurement disaster is more than balanced by its long-term benefits – not all of which can be quantified by a desiccated calculating machine. Hopefully the promoters of the Queensferry Crossing and the new V&A Museum in Dundee are paying attention.

|

|

Read next: Japan: Modular Man

Read previous: Holyrood North: Victory for Digs

Back to October 2016

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.