Bradford: Woolly Mammoth

17 Oct 2016

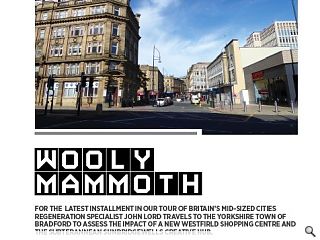

For the latest installment in our tour of Britain’s mid-sized cities regeneration specialist John Lord travels to the Yorkshire town of Bradford to assess the impact of a new Westfield shopping centre and the subterannean Sunbridgewells creative hub.

Just now, it’s tempting to view all English cities through the lens of the Brexit vote. What started as a series of essays on England’s struggling cities has, unwittingly, turned into a grand tour of Brexitland. We’ve already been to Stoke and Hull, and visits to Blackpool and Sunderland are planned for 2017. All four are among the places where anti-EU sentiment was strongest. This time we look at Bradford, undoubtedly a struggling city but a place where opinion was more evenly divided. It is a remarkable city facing a deeply uncertain future.Much of the post-referendum debate has focused on what the vote told us about a deeply divided society, while inviting us to reflect on why the story in Scotland and London was so different.

Research by Matthew Goodwin and Oliver Heath concludes that: “The public vote for Brexit was anchored predominantly, albeit not exclusively, in areas of the country that are filled with pensioners, low skilled and less well educated blue-collar workers and citizens who have been pushed to the margins not only by the economic transformation of the country over recent decades but also by the values that have come to dominate a more socially liberal media and political class. In this respect the vote for Brexit was delivered by the “left behind” – social groups that are united by a general sense of insecurity, pessimism and marginalization, who do not feel as though elites… share their values, represent their interests and generally empathize with their intense angst about rapid social, economic and cultural change.1

As Laurie Penny put it in the immediate aftermath of the vote, this was “a referendum on the modern world”.2 Certainly, the modern world hasn’t treated Stoke, Hull, Blackpool or Sunderland kindly. It has decimated their traditional industries and all four cities have struggled to find a foothold in the high-value, knowledge-intensive service sectors that have driven growth in the successful national and regional capitals. The same can be said of Bradford, once the capital of the worsted woollen industry, but now a distinctly second-class power with a fair-to-middling university, operating in the shadow of its neighbour Leeds and afflicted by persistent poverty and deprivation. Bradford also voted to leave the EU, but the margin – 54% to 46% - was more or less in line with the average for England. It was by no means one of the Brexit heartlands. One explanation for this is that Bradford is the youngest English city outside London, and young people tended to vote remain.3 Another is that Bradford is more ethnically diverse than the other cities in the group, and “places with large non-white populations tended to be somewhat less likely to vote leave”.

This is a big city. The council area has a population of 523,000. About 315,000 people live in the city proper, with the rest distributed across the small towns and rural hinterland to the north. Despite its youthful population, the employment rate is low, unemployment is high and wages are below average. Bradford remains dependent on the public sector and jobs growth in the private sector has been weak.4 It faces some of the same problems as other “regional second cities” like Sunderland and Sheffield. Historically, Bradford was heavily dependent on a single industry, in this case wool. While the neighbouring regional capital, Leeds, has diversified into business, professional and financial services, digital media, science and technology Bradford has stumbled through a century of steady decline.

A few years ago, the Centre for Cities published Cities Outlook 1901, an absorbingly interesting overview of the urban hierarchy of England and Wales (but, frustratingly, not Scotland) and how it changed over the course of the 20th century. In an age when local politicians and city managers are susceptible to the superficial prescriptions of persuasive charlatans, the report is a timely reminder of the power of history to shape the trajectory of change.

For Bradford, the story is grim. In 1901, it was the 8th largest city in England, a relatively prosperous place with a high proportion of people (by the standards of the day) working in higher wage occupations, and property values well above the average for large industrial cities. As measured by the number of registered joint-stock companies Bradford was one of the most entrepreneurial cities in England & Wales. But, like its near neighbours in West Yorkshire and East Lancashire, the city was highly dependent on textile employment and other cyclical industries, while business and professional services were relatively under-developed. The Centre for Cities’ 1901 City Index shows that Bradford was one the most successful places in the country at that time, in spite of some warning signs. What followed in the course of the 20th century was a catastrophic decline – a steeper fall down the City Index rankings than any other industrial city. Bear in mind that larger cities have tended to fare better than medium-sized towns and the scale of Bradford’s humiliation becomes clear.

The seeds of decline were sown long before but it was in the second half of the 20th century that the crisis really manifested itself, with the closure of scores of woollen mills and other factories. Business at the wonderful Wool Exchange (Lockwood & Mawson, 1867 – now a branch of Waterstone’s) came to end in the 1960s. By then the city was busily engaged in trashing its superb architectural heritage, with a network of urban highways slicing through the city centre fringes, fatally compromising the integrity and scale of the high Victorian city and isolating the centre from the inner suburbs.5 What happened in that period is about as bad as it gets, and the combination of industrial decline and criminally inept planning is almost unbearably poignant. The quality of recent development is almost uniformly woeful, suggesting that no one has learned any lessons from the experience of the past 50 years. The immutable laws of the commercial property market still apply: distressed places get awful development, and awful development compounds their economic and social distress. Despite this, the places where 19th century Bradford survives in more or less complete form are absolutely superb and among the best of their kind in Britain. To see so much of this architectural heritage neglected, undervalued and under-used is heart-breaking.

The economy remains under-powered but the city is changing. Attention in recent years has focused on two major city centre projects: the creation of City Park (2012) and the long-running saga of The Broadway, a Westfield shopping mall which opened in late 2015. Taken together, these developments have radically reshaped the centre of Bradford. Both are discussed, perceptively and entertainingly, in Jones the Planner’s new book, Cities of the North.6 Jones doesn’t like City Park, which is described as “a dumbed-down, cost-engineered palimpsest” of elements of Will Alsop’s “eccentric” 2004 masterplan, “not so much a park as an entertainments plaza”. Others have been much more generous, including the Academy of Urbanism which gave City Park its Great Place Award in 2012. The assessment panel observed the park for a day and reported that: “… [it] gradually filled with people as the pool filled with water over a five hour cycle. And these were all the people of Bradford, youths on bikes, elderly people, women in burkas, students, families – a happy, relaxed mix of people rarely seen in British cities (other perhaps than on a beach) and certainly not in Bradford. It’s a place that makes you think that Bradford is going to be OK and makes you believe that the physical environment of a place really can be transformative.”

A study by the University of Bradford’s Centre for Applied Social Research was based on research carried out in the new park’s first year, and the responses were equally positive. Users praised the park’s “beauty and attractiveness”, and the success of the project “appeared to have raised aspirations and expectations” for regeneration elsewhere in the city centre. Importantly, the researchers found that City Park had become “a central hub” for people passing through the city centre on their everyday business. Bradford’s aspiration to create a democratic public space appeared to have been achieved: City Park can be enjoyed by everyone including people who may not be welcome in the quasi-public spaces of the retail and leisure malls.7

I find myself drawn to the middle ground of this debate. There’s no doubt that City Park has been a boon to Bradford and it is a superb resource for special events and celebrations. But, four years later and on a warm but overcast late summer afternoon, it seems an oddly cheerless place, listless rather than “vibrant”. There is a steady flow of pedestrian traffic, but it’s not that busy and the sheer scale of the square - with its “mirror pool” and umpteen fountains – and the lack of green space is mildly intimidating. A qualified success.

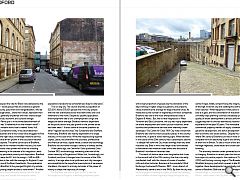

Until a year ago, when people talked about Bradford they talked about “the hole in the ground” – the huge tract of land acquired and cleared by Westfield for a new shopping mall that took a decade to bring to fruition. Work finally got under way as the economy staggered out of recession, and the first phase of The Broadway opened in the autumn of 2015. The spatial impact of the development is almost wholly negative: a bland superblock now interposes itself between the civic and commercial heart of the town and Little Germany (of which more later). There are routes through, but only during shopping hours. A new generation of malls (in Liverpool, Exeter, Canterbury and elsewhere) have been built around streets and are open all hours, but The Broadway is a throwback to the impenetrable sealed units that have sucked the life out of so many town and city centres.

Jones the Planner says The Broadway is “formulaic and exploitative”, and it is. On its own terms – that is, as a purely commercial proposition – The Broadway probably works well enough. The best of Bradford’s not very stellar chain stores are safely inside the box, with a load of cheap parking on the doorstep. But retail-led regeneration is a zero-sum game, which should not be confused with the much more challenging business of wealth creation. The point about retail expenditure is that it is more or less finite, and the fight is all about where people spend their money and, indeed, whether they spend it in shops at all or online. I suspect that The Broadway (and a contiguous development, The Exchange, which will open soon) will have helped to stem the flow of retail leakage from Bradford to Leeds and the out-of-town locations. How long that will last when Victoria Gate – with its flagship John Lewis store – opens in Leeds at the end of 2016 is anyone’s guess. What is absolutely certain is that The Broadway will intensify the pressure on Bradford’s traditional shopping streets, which are already suffering badly with a vacancy rate running at an eye-watering 23.4 per cent.8

The challenges facing Bradford are genuinely daunting and the politicians and officers charged with trying to steer the city towards a more prosperous and sustainable future deserve our sympathy. You might argue that they’ve made a thoroughgoing mess of the job for at least 50 years, but bad decisions are the inevitable consequence of the relentless day-to-day pressures of governing a struggling city with inadequate resources and limited powers. What any dispassionate observer can see is absolutely rock-bottom stuff (try the Forster Square Shopping Park or the horrible Leisure Exchange) starts to look like manna from heaven. Any development, however banal and cynical, is better than none.

But there are grounds for at least qualified optimism. Despite the battering it has received for half a century Bradford is still, somehow, an amazing place. It is one of those gold rush stories: in the middle years of the 19th century the mechanisation of the textile industry transformed a middling-size industrial town into a place of global significance. In the “golden years” of the 1860s and 1870s the city centre was almost entirely rebuilt under the pragmatic influence of the council’s Street Improvement Committee: “The result was rarely less than harmonious and dignified, the buildings predominantly although not exclusively Italianate in style, in the fine local sandstone ashlar”.9 The heart of the city is still packed with superb civic and commercial buildings of this era, of which the Wool Exchange – boldly and cleverly adapted in the 1990s – the City Hall and St George’s Hall are the most striking examples. There are plenty of other delights in the traditional retail core that extends north of here, but the distressed state of many of the businesses and properties is palpable. There is a surplus of retail stock and any number of vacant and under-used buildings.

Sunbridgewells is one local developer’s attempt to revive the fortunes of the city centre. The scheme will convert the cellars of a long-demolished brewery into a Victorian-themed underground street of bars and shops. Easy-in, easy-out lease terms are designed to attract young entrepreneurs. It sounds like a similar formula to the successful Forum in Sheffield, but it begs the question why, with so many spaces available on the city streets, anyone would choose to go underground. It would be nice to see enterprise rewarded, but several missed opening dates do not instil confidence.

Little Germany, marooned by major roads and cut off from the city centre by The Broadway, is the only warehouse precinct in Bradford to survive more or less intact. Development of the area began in the 1850s resulting in a memorable townscape of narrow, canyon streets flanked by tall warehouses climbing up the hill from Leeds Road. Predictably enough, the area has been colonised by tech businesses and apartments but the amount of empty space and the lack of cafes and bars confirms that progress has been slow. Everywhere you go in Bradford, demand – or the lack of it – is the key issue.

That said, something quite exciting seems to be happening in Goitside, a former industrial area west of the city centre with a seemingly unlimited stock of derelict mills and other factories. Historic England has put the conservation area on the heritage at risk register, describing its condition as “very bad” and the trend as “deteriorating”. The former judgement still holds true but the latter, to judge by the amount of construction work, may no longer apply. The creative economy is establishing a foothold in the area, and a number of other projects involve the conversion of redundant mills into student flats. This can be a mixed blessing, but in this case it is all for the good, preserving Bradford’s industrial heritage and creating a stock of student housing in buildings of a quality far better than anything the specialist developers would ever consider. Credit also to Historic England for commissioning a practical and inspirational new guide to securing “active and sustainable futures” for West Yorkshire’s redundant textile mills.10 In nearby Longlands, a social housing provider has refurbished early 20th century council housing and built new homes to rent in what was previously one of the poorest parts of an impoverished city. All this is happening in the shadow of one Bradford’s most remarkable and reviled buildings, the 1970s brutalist classic, Highpoint.

Goitside is full of good things, but it can’t match the architectural quality of Little Germany. Despite this it seems livelier, which says everything about the importance of location and connections. Thanks to The Broadway, Little Germany is stuck, barely visible, on the wrong side of a glossy retail barricade, but Goitside is nicely connected to the city centre, the college and the university. Whatever good things happen there in the future can flow seamlessly out into the rest of the city.

Bradford engages your mind and your heart. It’s the kind of place you desperately want to succeed, to become more than just a city with a great history. One obvious priority is transport, especially rail connections. The Leeds City Region Growth Deal includes something called the West Yorkshire Plus Transport Fund, which proves to be nothing much more than a package of piffling road improvements. Bradford’s miserable, dingy railway stations are the worst in any large English city, with the possible exception of Sunderland. Both are termini, crying out to be connected by a short crossrail link so that a decent city station can be created, connected to Leeds, Manchester and London by fast, modern electric trains. That some people consider these basic requirements for a dynamic city economy to be outlandishly ambitious tells us a lot about the country we live in, its poverty of ambition and its willingness to leave a great city to sink into terminal decline. No western European city of comparable scale would tolerate such pitifully inadequate infrastructure: that tells us something about the quality of urban life in the continent we have decided to leave behind.

1. Matthew Goodwin and Oliver Heath, “The 2016 Referendum, Brexit and the Left Behind: An Aggregate-Level Analysis of the Result”, London School of Economics, July 2016

2. New Statesman, 24 June 2016.

3. City of Bradford, Understanding Bradford District, September 2013

4. Centre for Cities, Cities Factbook 2016

5. The carnage is recorded in Gavin Stamp, Britain’s Lost Cities, Aurum Press, London 2007

6. Jones the Planner, Cities of the North, Five Leaves Publications, Nottingham, 2016.

7. University of Bradford Centre for Applied Social Research, ‘A Great Meeting Place’: A Study of Bradford’s City Park, 2014

8. Local Data Company quoted in the Telegraph and Argus, 24 August 2016

9. Peter Leach and Nikolaus Pevsner, The Buildings of England – Yorkshire West Riding: Leeds, Bradford and the North, Yale University Press, 2009. See also John Ayers, Architecture in Bradford, Bradford Civic Society, 1973

10. Historic England, Engines of Prosperity: new uses for old mills, 2016

|

|

Read next: Cove Park: Mountain Retreat

Read previous: Stirling: Six Pack

Back to October 2016

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.