Wood for Good: Lumbering Up

12 Jul 2016

Scotland may be a UK leader in the use of timber but it still has far to go to fulfill its true potential. In an effort to find out more about this wonder material Urban Realm sat in on wood for good’s spring conference to see how this most sustainable of products is being put to use in new and innovative ways.

Growing appreciation of the role timber has to play in solving Britain’s worsening housing crisis has prompted Wood for Good to lay on a series of four one-day events to explore a variety of inter-related housing themes. Attending the first of these, The Innovative Timber House, Urban Realm saw at first-hand how the perception of timber as more than just a building material is beginning to take root.Themed on the use of timber in modern housing design to build more, better, cheaper and bigger houses the event looked at the provision of urban, suburban and rural homes via a variety of products and systems which could help in meeting ambitious construction targets through to 2020.

Peter Wilson, director at conference organisers Timber Design initiatives, said: “The purpose for Wood for Good’s point of view is looking at what can be done for housing in the UK, we want to find new ways of doing things. We want to share ideas and technologies and build better, bigger houses. It’s not just can we build houses with timber but can we build them at all.”

One speaker at the event was Matthew Benson, head of land & development, new homes and research at Rettie & Co, who complained that you can ‘set your watch’ by an 18 year boom bust cycle and it’s time to try a different model. He said: “As land prices rise, buyers need more credit to purchase the land. Appreciated land serves as collateral for more loans and so on,” contributing to a vicious cycle of ‘buy, build, bugger off and go broke’ amongst the major house builders.

Outlining one example of how things can go awry Rettie highlighted the experience of Mactaggart & Mickel at Polnoon where they took land already in their possession and looked at maximising efficiency. Rettie said: “They redesigned it on designing for streets principles to end up with more flats, with more variety but the overall build costs were higher than the computer designed plan of 2004 - as a result although prices were higher the overall profit margin was less. The maths is there – design doesn’t pay.”

Proffering an alternative vision Benson said: “Imagine we had a housebuilding delivery model where it cost 25 per cent less to occupy the house, deposit requirements were 50 per cent lower and house builders were competing on the quality of their design and place making.” To reach this Nirvana Benson advocated a new model, he explained: “What happens if you take the land and infrastructure and you didn’t pay for them from the house builder’s balance sheet but over the long term on another balance sheet? That leaves the house builder to fund the bricks and the mortar. The developer now doesn’t need as much profit as they are not investing as much money.

“If you buy a £300k house now you will pay £1,500 per month for that mortgage. If you take out a mortgage only to pay for the bricks and mortar then on the same terms you pay £790 per month plus an annual charge to service the bond that built the infrastructure as well as a monthly sum for the use and ability to buy the land over an 80 year period. The combined payment there £1,180 and I only need a deposit on the £790- so my deposit id £14k not £30k.

“That saving of £320 per month you could spend £43 per square foot more on the building or 523sq/ft bigger. Or you could save the money. You’re using a much more cost effective use of funds rather than the very expensive, short term balance sheet of the house builder and you’re using the long term money to finance the long term elements of what goes into a house.

“If the local authority stumped up £60k for the infrastructure, the homeowner is paying for that through a top up on their council tax at a 4.5 per cent fixed rate of interest. Finance that over 50 years £210 per month. The local authority can borrow that money at 3.5 per cent over the same period of time so that’s £177 per month so the local authority is generating an annual income of nearly £400 per unit.”

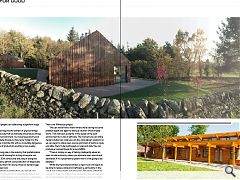

Amongst those seeking to make a difference is Wikihouse, an open source design solution initiated by London based Architecture 00 which recently delivered a community meeting space in Edinburgh for the Fountainbridge Canalside Initiative. Overseen by architect Akiko Kobayashi this facility was put together over the course of a single weekend courtesy of a small band of volunteers and simple mallets and pegs.

Citing the likes of Wikipedia, YouTube, Airbnb Alastair Parvin, vision and product lead, of the Wikihouse digital build solution, outlined how this can be made possible: “Our dependence on a tiny number of huge players who build a tiny number of one size fits all homes and try to sell them – and they might not even do that. The digital revolution has moved us from models where we are totally dependent on massive centralised models of production and distribution, to models where many small players can collectively outperform large ones.

“That’s now coming into the domain of physical things and will change the way that we fabricate and produce things, especially the built environment. Our housing economy and industry are complete dinosaurs, they never made it to the 20th century never mind the 21st with an incredibly dangerous and messy system of production resulting in low quality homes.

“There’s a running joke in the industry that prefabrication has been the future of housing for as long as anyone can remember. In the 20th century the only way of doing this was large scale heavy upfront cost production on large scale factory models. You then hit a slump, there’s a demand gap and the factory goes bust.

“Now we’re entering a world where you can set up a factory for £15k in a garage to form a distributed network of Maklab’s and distributed spaces, pop up factories. Collectively they are very resilient and can outperform the major players. That is the Wikihouse project.

“We can move from a world where we’re solving the same problem again and again to taking a solution which already works. That will be as powerful in the design of the built environment as it was in software. The moment you can share design solutions as code you can also code design solutions so we can begin to share open source grammars of joints as code and allow them to be built based on rules and data. You can produce a two bed house for around £60k.

“There is simply no way of talking intelligently about an open circular economy unless you embrace open source and standards, If it’s a proprietary system then it’s not going to be adopted. “

Whilst the trend toward timber is clear much still needs to be done to reduce waste and inefficiency, particularly in the use of new components and processes. This alone will not be enough to break the logjam in housebuilding but with demand for accommodation still going through the roof we must take every opportunity available.

|

|

Read next: Sighthill: Northern Exposure

Read previous: Port Dundas - Windy City

Back to July 2016

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.