Grey Gardens: Concrete Feats

22 Apr 2016

With St Peter’s Seminary in the public spotlight for hinterland Brutalism is now back in the limelight, prompting architectural journalist Mark Chalmers to look again at a much maligned style through the lens of hindsight. Along the way Chalmers revisits Peter Wormersley’s buildings as well as Cardross and Cumbernauld whilst finding time to review Grey Gardens - a Dundee Contemporary Arts exhibition seeking to ‘rehabilitate’ Brutalism in the eyes of the public.

Blame Reyner Banham …The architecture critic’s final books, A Concrete Atlantis and Scenes in America Deserta, are by turns introspective and lyrical – but he made his name with forceful ideas in, Theory and Design in the First Machine Age and The New Brutalism: Ethic or Aesthetic. In 1966, the latter introduced Brutalism to the wider world.

Until an idea gains a name, there’s nothing to identify with or react against. Soon after it became Brutalism, this architecture became synonymous with the “brutal” environments of run-down tower blocks, megastructures and deck-access housing. However, its origins lie simply in the French phrase - béton brut – or raw concrete.

Brutalist buildings prove that concrete is the universal material. You can build walls, beams, columns, floors, roofs, shafts and stairs from it. Concrete is load-bearing, fire-proof, it can be made waterproof, and you can sculpt it; it can also take any surface from smooth polish to heavy rustication and bas relief.

In the popular mind, New Brutalism is a movement from the 1960’s, but its starting point for some are Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitations of 1950’s. For others, it sprang from the “Nybrutalism” coined by Hans Asplund in Sweden at the end of the 1940’s. In fact, by the time Banham’s book was published there were almost two decades’ worth of buildings which might fit the description, so Banham knew it wasn’t a passing fad.

1966 may have been Brutalism’s high water mark, but this generation of buildings has now reached the age when architecture suddenly disappears in a cloud of dust. The High Tech buildings which followed them will be easy to demolish – but the Brutalists built to last and demolishing concrete-framed tower blocks takes a great deal of effort and Semtex. Basil Spence’s Hutchesontown “C” towers in the Gorbals were among the first to go, in a controversial explosive demolition which took the life of an onlooker in 1993.

At that point, Brutalism was so far out of favour that no-one seemed to care about preserving either the buildings or the legacy of those who designed them. Two decades later, the Twentieth Century Society has recognised the best of what remains, a number have been listed and wider interest has grown around a number of websites, books and exhibitions.

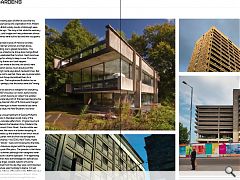

“Grey Gardens” opened recently at Dundee Contemporary Arts (DCA) – a new exhibition which explores how concrete architecture from the 1960’s relates to the landscape. It’s an introduction to Scottish Brutalism, using examples drawn from Peter Womersley’s work around the Borders, St Peter’s Seminary at Cardross and public art in New Towns such as Glenrothes. It contrasts them against more exotic fare, such as Carlo Scarpa’s Brion Tomb and Edward James’s sculpture garden at Las Pozas.

The exhibition forms part of the 2016 Festival of Architecture and although it sidesteps the social and political fall-out of Brutalism, it does demonstrate how muscular concrete was softened through its relationship to the landscape, particularly in the case of houses by Peter Womersley and Morris & Steedman.

As you enter the main gallery at DCA, Womersley’s Bernat Klein Studio is the first thing you see. Restoration of the studio appears to have stalled again, but Womersley remains an enigma which has attracted a small band of dedicated fans. They’re less vocal than the champions of Cardross who were taught by Andy and Isi at the Mac, but their forthcoming rewards are a Womersley exhibition and book, due to appear later in the year.

The working drawings for the Bernat Klein Studio are fascinating, and force us to look at Womersley in a new light. Dyeline prints from November 1970 show that the studio’s core and floor structure are in-situ concrete, but the columns and balustrade panels are precast. Look more closely and you discover that the gable trusses were changed to steel hollow sections during the design process: so form-making came first for Womersley, well ahead of any sense of purism about materials and process.

Grey Gardens culminates during April in a Salon, which will be held in a well-known architect’s former house in a Dundee suburb. There we’ll have the chance to see how the early 1970’s have been carefully preserved, and perhaps find out whether the original spirit of Brutalism survives.

Grey Gardens, along with the www.scotbrut.co.uk website; Owen Hatherley’s essay “The Brutishness of British Modernism”; Jonathan Meades’s documentary “Bunkers, Brutalism, Bloodymindedness”; and Jon Grindrod’s book, “Concretopia”, presents Brutalism with a matter-of-fact simplicity. The graphics are simple with flat colours and clean typography, sometimes accompanied by Isotype pictograms of stick figures cycling, walking or dropping litter in bins.

All very Sixties. Retro-philia is a powerful force among curators and commissioning editors; perhaps it was inevitable that Brutalism would be re-evaluated. When younger architects discovered it for the first time, they found little to document what it was and what it stood for, apart from a few books which were contemporary with the buildings. For that reason, Brutalism is a loose school.

If there is a Brutalist canon it probably includes the Barbican in London, Park Hill in Sheffield and the “Get Carter” car park in Gateshead. In Scotland, Cumbernauld Town Centre, the Hunterian Gallery and Leith Fort are among the best-known. Nonetheless, there are truer examples of the original, Reyner Banham, sense of Brutalism: unadorned concrete with an off-the-shutter finish.

Three in particular spring to mind, each one a long way from Brutalism’s usual suspects located in the Comprehensive Development Area (CDA) projects of Glasgow city centre and New Towns spread across Fife, the Lothians and Lanarkshire.

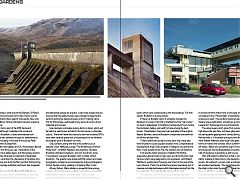

First are the hydro schemes in Highland Perthshire, especially Lubreoch Dam in Glen Lyon and Errochty Dam near Calvine, which were designed by civil engineers, with Robert Matthew’s guiding hand hovering over them in the case of the Lyon scheme. There, the architecture grows seamlessly out of massive concrete buttresses which themselves spring from the mountainside. Concrete literally emerges from rock.

The reservoir at Errochty is impounded by a diamond-headed buttress dam: at sixteen storeys high and almost three-quarters of a kilometre long, it is one of the largest in Europe. It consists of half a million tons of concrete, and must be considered a true “Fitzcarraldo” undertaking in such a remote, snowbound spot. The ancillary buildings designed by James Shearer are pure Brutalist, sometimes reminiscent of Sigurd Lewerentz’s final projects around Stockholm.

The valve towers which grow from Lubreoch Dam rear up high above the glen floor and have glass penthouses, using the same patent glazing which James Stirling used at Andrew Melville Halls in St Andrews during his own Brutalist period. Here, Robert Matthew used rough-cast glass to reveal the forms of motors and winches which control the massive draw-off valves. Béton brut somehow seems more apt for these structures set into the Breadalbane mountains, then for student halls of residence overlooking a golf course.

Part of Brutalism’s attraction is that in-situ concrete is a plastic material, limited only by the dexterity of the formwork joiners. At Lubreoch, curved, cubic and faceted geometries are resolved seamlessly. You can achieve almost any form, and the style’s critics miss the point that visual concrete – just like stone and timber – weathers naturally. If detailed correctly (the Concrete Society can help with this), pattern staining and black streaks can usually be avoided.

Secondly, although the preservation lobby seized on St Peter’s and after twenty years of effort it looks like the seminary will be preserved by arts organisation NVA, William Kininmonth’s North British whisky bonds in Edinburgh were demolished a decade ago. The irony is that while the seminary suffered from leaks, cold bridges and was problematic almost from day one, the bonds were built to last and their occupants never complained.

The bonds comprised a series of massive concrete buildings with small barred windows, and high above, sculptural roofs floating over a glazed clerestorey. The exciseman must have smiled as he drove down Gorgie Road, because their form celebrated their function. Each bond was an impregnable keep for whisky to sleep in over 12 or more years, undisturbed by thieves and cask-tappers.

As Malcolm Fraser wrote at the time, the bonds were modern fortresses which said as much about post-War Scotland as Edinburgh Castle says about medieval times. But public opinion chose not to see that, there was no preservation campaign, and Forrest Group demolished them for a Sainsbury’s superstore. That emphasises Brutalism has an image problem – or perhaps, that the bonds were the “wrong kind of Brutalism”…

Finally, concrete has become a metaphor for everything that’s wrong with 1960’s housing: run-down, dysfunctional, inhumane buildings which became so-called “sink estates”. The frightening concrete labyrinth of Thamesmead became the backdrop for Stanley Kubrick’s film of “A Clockwork Orange”, and the social engineering at its heart received a bad name from which its house style, the New Brutalism, has never recovered.

Despite that, the unique treatment of George McKeith’s Castlehill tower blocks in Aberdeen avoids many of the problems that plain concrete suffers from. Virginia Court and Marischal Court sit behind the Salvation Army Citadel in the Castlegate and command Union Street. Granite rubble was cast into the spandrels, like raisins in a clootie dumpling, to give it a grain that breaks up the streams of rain which would otherwise stain the panels with dirt from the atmosphere.

Most Brutalist schemes – the CDA’s, New Towns, Hydro schemes and tower blocks – were commissioned by the state. So this is political architecture, aligned with the progressive social policies of the post-War years. The paradox is that these supposedly utopian schemes (although their designers never described them as such) became dystopian. In re-appraising Brutalism, most authors have acknowledged its deficiencies while pointing to the larger, societal, reasons why some buildings were doomed from the day they were commissioned.

Perhaps architecture wasn’t entirely to blame. Is it just coincidence that the collapse of Socialism in the 1980’s also saw a movement against Brutalist architecture in Britain? Home ownership and community architecture sought their own expression in romantic rationalism and the neo-vernacular. The monumental and the concrete were rejected in Scotland, although Brutalism continued in the socialist states of the Eastern Bloc through to the mid-1980’s.

Since it’s impossible to disentangle how something looks from how it works and why it was built, the Grey Gardens exhibition only tells part of Brutalism’s story. What’s missing is an explanation of why it fell out of fashion in the 70’s, became “most hated” in the 80’s, then much was destroyed in the 90’s and early years of this century before architectural fashion embraced it again.

In fact, Brutalism’s rehabilitation among the critics neatly demonstrates Banham’s axiom that, “The only way to prove you have a mind is to change it occasionally”.

|

|

Read next: Gareth Hoskins: Last Respects

Read previous: Stevenson Building: Fit for Purpose

Back to April 2016

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.