Cottonopolis: Mills & Boom

22 Apr 2016

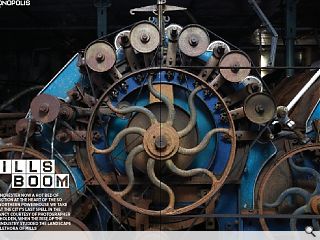

With Manchester now a hot bed of construction at the heart of the so called northern powerhouse we take a look at the city’s last spell in the ascendancy courtesy of photographer Darren Holden, when the rise of the cotton industry studded the landscape with a plethora of mills

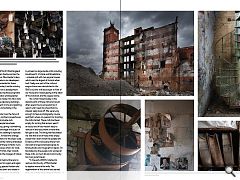

The cotton mills of North West England have long cast their shadow across the area’s history but as Manchester’s days as a boom town return can developers cotton on to the potential for these remnants of yesterday’s textile industry to serve as tomorrow’s development opportunity. Capturing these enigmatic structures in transition photographer Darren Holden has made it his life’s work to document these decaying buildings, capturing a moment in time and granting them a degree of immortality in the process.With Manchester now the focus of the government’s northern powerhouse agenda public and private cash, businesses and people have been pouring into the city, giving it something of a second wind amongst the clutch of British conurbations seeking to replicate London’s success. Amidst this change Holden remains drawn to the sheer scale, sense of decay and the history embodied in the brick walls of these romantic ruins as he seeks out spaces which, for most, lie tantalisingly off-limits, their innards having given out to the ravages of nature and neglect.

Emerging from behind the lens to explain what draws him again and again to these crumbling spaces Holden told Urban Realm: “I was born and raised in Reddish, Stockport, a town dominated by at least six large textile mills including Houldsworth, Victoria and Broadstone - a double mill with two engine houses which was the largest of its kind when built. Sadly one part of the mill and engine house was demolished in the 1960’s but this mill stood right in front of our house and I loved gazing at the detail of the windows and the copper dome.

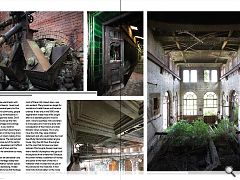

“As a child I loved to play in the derelict parts of these mills and would often spend hours just exploring. It wasn’t until I went to school that my interest really took off. We were lucky enough to have a photography course and that’s where my passion for shooting the mills started. These mills had been empty for so long that access wasn’t an issue, lots of kids made it easy to venture in and document a world that few got to see. The thing that fascinated me was that a lot of these mills simply closed their doors when the people left. Evidence of this was everywhere from old coats and personal belongings to family photos and mugs left on desks. I’m fascinated by the people who worked at these mills, so much life and community has now gone forever.

“In the early 2000’s I started to venture into the city of Manchester to explore more of the mills. The regeneration of the centre had started and a lot of mills were being converted into New York style apartments with exposed brick and beams, I even lived in one myself for several years but the apartments had no community; people just wanted to keep to themselves in their little very expensive boxes. Don’t get me wrong I love to see the mills converted and heritage and buildings regulations make it very hard for developers to knock them down there’s nothing worse than a mill burning down, too many mills burn down making it too much of a coincidence. The real sad part is the more you move out of the centre the worse it gets, developers can’t afford to convert mills out of town and the council won’t pay for demolition so many are left to rot.”

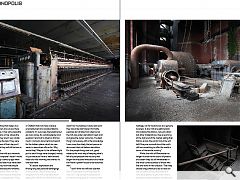

Asked whether we take better care of our shared mill heritage today than in the past and whether derelict spaces are on the rise or decreasing, Holden said: “I think it’s safe to say that heritage in the 1970 and 1980s,shortly after most of these mills closed down, was non-existent. Many became a target for vandals and metal thieves and became unloved. It was only in the 1990’s that regeneration made these mills sought after as a desirable place to live and work. I love to see these mills converted to living space and most are done with consideration of their history and look fantastic when complete. This is why I love the mills, they were all about statement and who could make the most beautifully tiled and decorated engine house. Very few still have the engines but the ones that do have now been restored. Most engine houses never saw than a handful of people so why go to all the expense of the ornate tiles? Because the owner wanted a statement of money and power at the heart of the mill, it mattered what it looked like not just on the outside but the inside too. In fact most mills do look better on the inside and one of my favourites is Swan Mill No 3 in Bolton. The thing that makes it so special is the corners are curved, there are no right angles. It has some beautiful detailing with swans on top where the drain pipes are. They aren’t very visible but stunning none the less. They were the Beetham towers of their day and I would like to think they will still be here in another 100 years.

“Whilst I see the mills as a romantic place to work and explore I doubt I would feel the same way a century ago when the noise, dust and heat must have been unbearable. It’s only now that they lie silent that they have become romantic. I look at them as works of art not the beating heart of the industrial revolution giving thousands of people work. They represent towns such as Bradford or Oldham that now have massive unemployment and social problems, problems I’m sure were there before but are now worse. As a photographer and explorer I tend not to dwell on this too much, I come to document and search for the hidden places which no-one wants to leave their offices for. Why would they? Maybe it’s the different light just to see if things have changed, mostly it’s just because I love to walk around these old mills knowing that there’s no one else there.

“It’s about exploration and finding long lost personal belongings or documents. I found the original blueprints for a mill under demolition dating from 1905 from Stott & Sons, the most famous of all the mill architects. If it wasn’t for me looking in dusty old room they would be lost forever. Normally explores do not take from sites but as the mill was under demolition I kept a lot and gave the owner some too. The best thing I come away with is the knowledge I was more than likely the last person to document that mill before demolition. For the people living next to it, good riddance for me a way of keeping what’s left of quite possible the industry that began the industrial revolution and made the North a power house to be reckoned with.

“I don’t think we will ever see that kind of scale again but things need to move on. They served the purpose of an industry long gone. It’s only now that some mill owners are trying to save this heritage, not for tourists but as a genuine business. A few mills are getting back into making fine fabrics, not just cotton but other materials too, they are aiming at the high end of the market selling their fabrics across the world. Only time will tell if they are successful and the north still has something to offer the world in terms of the textile industry.”

Whilst the mills of Manchester no longer thunder to the sound of pistons and steam they do still reverberate in the wider consciousness of those who live and work in their shadow. That they should long continue to do so rests on the shoulders of the passionate few who are prepared to give their time to promotion these forgotten wonders to a broader audience.

|

|

Read next: Lairdsland Primary

Read previous: Gareth Hoskins: Last Respects

Back to April 2016

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.