Stoke-on-Trent: Pottering Along

13 Jan 2016

The Staffordshire city of Stoke-on-Trent may lack a heart but it does not lack heart for that. Centre of Britain’s pottery industry Stoke has struggled to gel into a cohesive whole that is greater than the sum of its disparate parts. Here Yellowbook’s John Lord pounds its streets in a vain search for diamonds amidst the rough.

Pevsner’s 1974 The Buildings of England: Staffordshire disposed of Stoke-on-Trent in 15 cursory and dismissive pages; his introduction pulled no punches:

“The Five Towns are an urban tragedy. Here is the national seat of an industry, here is the fourteenth largest city in England, and what is it? Five towns – or, to be correct, six – and on the whole mean towns hopelessly interconnected now by factories, by streets of slummy cottages, by better suburban areas. There is no centre to the whole, not even an attempt at one, and there are not even in all six towns real local centres.”

Matthew Rice’s affectionate The Lost City of Stoke-on-Trent admits that Stoke is “a mess”, the six towns:3“…are linked but never in a felicitous or definitive way, and while each is held to have particular specialities to an outside eye these are well hidden. The all-pervading air of decay is common to the whole city…the linear and fragmented nature of the city’s plan means that a drive through the middle of the area takes you not from the outer margins to the obvious centre but through a whole series of outer rings…”

Faced with the challenge of post-industrial decline, Stoke-on-Trent resorted to the wholesale destruction of a townscape which, “urban tragedy” or not, was totally unique. Almost all the characteristic bottle kilns have gone: in 1958 2,000 were still in use, now just 47 remain. Even Pevsner acknowledged that the destruction of the kilns was “a great loss”:

“…their odd shapes were the one distinguishing feature of the Five Towns and used to determine their character – kilns bottle-shaped, kilns conical, kilns like chimneys with swollen bases. They have a way of turning up in views with parish churches and town halls as their neighbours.”

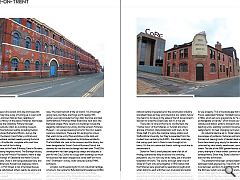

You can get a flavour of the classic Potteries’ townscape in Longton, where the Gladstone Pottery has been preserved, miraculously intact, as a working museum. There are other fine factories nearby, including Hudson & Middleton’s restored Sutherland Works. Just up the road, in Fenton, the Heron Cross Pottery is still at work in a traditional potbank nestled sweetly among the brick terraced houses. A bottle kiln, complete with small tree, emerges from the roof of the building.

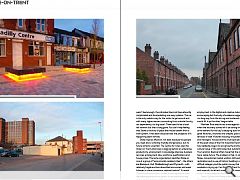

Middleport, next to the Trent & Mersey Canal in Burslem, is another interesting neighbourhood. The Burleigh factory, recently restored by the Prince’s Foundation, marks a step up from the workshops of Gladstone and Heron Cross to true industrial scale. China is still being produced here, and is popular with American, Korean and Japanese visitors. Across the road, in Port Street, a row of terraced houses has been smartly refurbished; others nearby lie empty and shuttered, a legacy of Stoke’s disastrous experiment with housing market renewal.

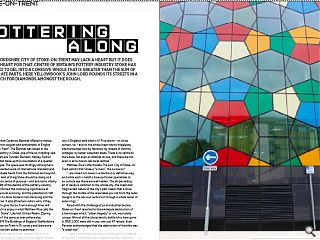

Hanley is the designated city centre and it is, as Pevsner says, “the most townish of the six towns”. It’s a thorough-going mess, but there are things worth seeing: 19th century survivals include the Town Hall, the brick and tiled Staffordshire & Potteries Water Board and, next door, the Bethesda chapel. More recent civic buildings include the elegantly restrained City Library and the lumpish Potteries Museum – an unprepossessing home for the city’s superb ceramics collections. These are thin pickings for a town that wants to be a city. More ambitious is the bold and confident bus station designed by Grimshaw architects. The Smithfield site, next to the museum and the library, has been designated as Stoke’s Central Business District but demand for the first two buildings has been slow. The £55m development has been plagued by delays and disputes: a plan for the City Council to occupy both buildings (so much for business) has been dropped but some staff will move into 1 Smithfield – a shiny, multi-coloured job by RHWL architects.

Longton, worth exploring for its rich industrial heritage, is home to the Centre for Refurbishment Excellence (CORE) which combines the new-build Stoke Studio College with the conversion of the former Enson pottery and the America Hotel. The £11.4m CORE project is “a one stop, national centre of excellence for the construction industry and allied trades as they work towards a low carbon future”. One fears for its future in the wake of the UK Government’s decision to scrap the Green Deal, but it’s a nice job.

There was no time on this trip to visit Burslem, the “mother town” of the Potteries, or Tunstall and only a glimpse of Fenton, that problematic sixth town. As for Stoke itself, it’s got a fine mainline railway station and Staffordshire University, but they’re separated from the modest town centre by the A500 – the urban motorway that swings past (and in Stoke’s case through) all six towns. It’s the civic centre but there’s nothing much else to recommend it.

Stoke-on-Trent’s small pleasures take a fair bit of finding, scattered as they are across this rambling, polycentric city. It’s not a city at all, really, just a reluctant federation of towns. The county borough (later city) of Stoke-on-Trent only came together in 1910; before that the Potteries were governed by separate boroughs and urban districts, each with their own municipal and public buildings. The result was the sextuplication of just about everything, and the long term consequences have been an absence of any kind of civic presence, and a surplus of hard-to-use property. This is the landscape that inspired Cedric Price’s celebrated Potteries Thinkbelt concept, published in 1966, which set out a programme for “a new kind of exchangeable university” which would use redundant railways and station yards to transport and assemble teaching units, enabling “constant movements and realignments” to meet changing curriculum requirements.4

As industrial decline set in, Stoke’s densely packed townscapes of potbanks, factories and terraced houses was thinned out, leaving tracts of derelict land and buildings. Some have been lying empty for decades, others have been colonised by retail sheds, warehouses, casinos and chain hotels. The site of the 1986 garden festival is a particularly dreary example of these lowest common denominator developments. Either way, Stoke’s distinctive character has been terribly diminished.

The problems have been compounded by some deranged roads engineering. The A500, which runs in a loop between junctions 15 and 16 of the M6, is a brute and the A50 spur which runs past Fenton and Longton is no better. Stoke gets the worst of it, because the A500 smacks straight through the town centre, but the whole city is dominated by crudely over-engineered highways. As if this wasn’t bad enough, the individual towns all have absurdly complicated and disorientating one-way systems. The car is the only realistic way for the visitor to get around and, with many higher earners commuting from outside the city, car dependency is a big issue5. There used to be a local rail network but that is long gone. You can’t help feeling that Stoke is the kind of place that would benefit from a tram system. It has been discussed but the prospects of it happening seem remote.

Stoke inspires affection, not least because the people you meet are so unfailing friendly and generous, but its future remains uncertain. The Centre for Cities says the Stoke-on-Trent urban area is lagging behind on enterprise, productivity, employment in knowledge intensive business services, employment rate, workforce qualifications and house prices. The same organisation identifies Stoke as one of a group of “economically isolated cities” – the others are Blackpool, Hull, Middlesbrough and Plymouth - with relatively fragile and less diversified economies and weak linkages to more prosperous regional centres6. A recent Oxford Economics report strikes a more optimistic note, highlighting productivity growth in the manufacturing sector, above-average wage growth and an increase in employment in the digital and creative industries7. This is encouraging but the body of evidence suggests that Stoke is a long way from the strong and sustained recovery that would lift it up the cities’ league table.

Matthew Rice sees this as a race against time. If and when the recovery comes will it be strong enough to drive demand for the city’s decaying built heritage - “the great factories, churches and chapels, pubs and the terraces of neat Victorian housing, the pottery owners and managers’ houses and the municipal palaces of one of the great cities of the first Industrial Revolution”? Stoke has, belatedly, begun to recognise the architectural and cultural value of this diminished but substantial legacy. The Ceramics Biennial offers hope that the industry still has a viable future. The problem is that, in places like Stoke, conventional market wisdom still tends to put the restoration and re-use of historic buildings in the too difficult category and the public money that used to be available is drying up. Can Stoke-on-Trent find the energy and ingenuity to attract a new wave of investment and build a more prosperous future?

Stuart Gulliver, the former chief executive of Scottish Enterprise Glasgow, knows Stoke-on-Trent well and has acted a strategic economic adviser to the city. While other industrial cities pride themselves on an aggressive, macho culture, Gulliver says that Stoke is a “gentler” place, perhaps because women have played such an important part in the ceramics industry. He points out too that, while the other struggling cities named by the Centre for Cities are in peripheral locations, Stoke is ideally placed in the centre of England. Its inability to capitalise on this advantage may be partly because, equidistant from Manchester and Birmingham, it has failed to establish economic, cultural or governmental connections with either. That, in turn, is evidence of a failure of leadership in a city that has too often been a byword for weak governance.

Gulliver believes that Stoke’s ceramics cluster, which includes a number of important hi-tech businesses, is still the city’s key industry and has the potential to stimulate growth in other design and technology fields as well as cultural tourism. The city needs to mobilise the teaching and research strengths of its two universities, and to make a concerted effort to expand employment in business and professional services, science and technology.

As Gulliver points out, Stoke-on-Trent’s polycentric form may be a problem but it is a fundamental part of the city’s history, culture and politics. There is an opportunity to develop an urban design strategy which would celebrate the “Stokishness” of Stoke and make a virtue of it. One source of inspiration might be the Emscher Landschaftspark in the Ruhr region of Germany, where a battered and polluted industrial landscape has been restored and healed by a creative combination of afforestation, river restoration, walking and cycling networks, urban agriculture and new parks and leisure facilities. This regional-scale plan, combined with a commitment to excellent architecture and design and careful stewardship of industrial heritage has made the Ruhrgebeit beautiful and helped to attract new investment and talent. It could be the perfect model for Stoke.

|

|

Read next: Urban Realm TOP100 Architects 2016

Read previous: Ballantine Bo’ness

Back to January 2016

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.