Housing Crisis

13 Jan 2016

It is an issue which everyone recognises as the most pressing problem facing Britain today but has remained intractable for decades. In an effort to break the logjam the Scottish Civic Trust dedicated their annual conference to the housing crisis in an effort to identify potential solutions and (more importantly) put these into action.

The words housing and crisis have become inextricably linked over the past decade in the UK as supply shortages exacerbate growing demand. Sadly the response to this has been a wall vacillation, equivocation and procrastination. Into this unpromising context stepped the Scottish Civic Trust who dedicated their annual conference to tackling the question: “How can we provide quality, well-built, sustainable and affordable homes without adversely impacting on communities?”To debate the issues a number of built environment experts from the Scottish government, industry and academia were assembled to chew over the issues but notably absent from their number were any house builders, an oversight which the organisers will seek to rectify next year.

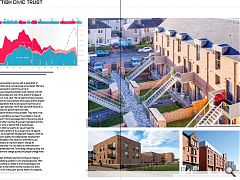

Concluding this debate was Bob Reid, director of planning at Halliday Fraser Munro and a key contributor to the land reform act, Reid drew attention to a graph produced by the RICS Housing commission report ‘Building a Better Scotland’ which tracked house prices against delivery from the 1920’s through to the present day. Amongst other things it shows how more houses were built in Scotland in 1944 than 2014, prompting Reid to remark: “If you contemplate the fact that most of the young male population in Scotland were still abroad that’s astonishing.”

Reid continued: “If you go to the early seventies and look at what’s been happening in terms of prices you will see that on an indexed basis a lot of other costs don’t show the same kind of increase, so there’s something that can’t be directly explained by economics which is happening here. Mortgage lengths, household income, even construction costs have not been changing to the same degree. To give you an idea of the degree to which they have been changing the average price in Scotland is now very near to £200k.

“You cannot ignore what is happening south of the border in terms of the overall crisis we are looking at. It’s significant at the end of September last year for the first time ever in London we got the average house price was over £500k. Nothing in economic terms or rational economic policy explains that and the differences to where we are in Scotland, which we should probably feel hard done by if we are property owners, there is nothing that explains it properly.

“Where I stay in Aberdeen property prices from 2000 to 2014 doubled, which again is exceptional and the root of the problems we are facing at the moment. If you compare average income to average house price by planning authority you can actually start to map where the problems exist. When I first bought my house in Glasgow way back in 1982 you used to work to a ratio of 3.5 times your income. There’s nowhere in the north east of Scotland now which prescribes to that rule and it’s pretty much the same in the rest of the country where you can go up to 4.5 and 7 times average income of £26,500, do the math. Homelessness is one of the most fundamental problems in terms of health and inequality that we have are going to have to deal with if we don’t crack this problem pretty soon.”

Reid refers to 1979 and the onset of a new Conservative government, as a key turning point in this narrative, as the state began to beat its long retreat from house building. Pointing to a nationwide reversal in the proportion of public and private housing between then and now Reid skirts the political dimension and leaves the stats hanging in the air for people to reach their own conclusions. Reid said: “When I first came back to work in Scotland in 1979 60 per cent of housing was in the public sector and 40 per cent in the private sector. In the generation since then we’ve gone totally the other way. I’m not commenting on whether that is good or bad but that is an incredible change for us to have to cope with.

“We are looking to the private rental sector as if it is some great panacea, I see it as a consequence where things have gone wrong rather than the solution. We’ve got to work with it, it’s the market, but it’s a consequence of how things have gone wrong. We’re now spending £2bn a year on hosuing benefit, we’d give our eye teeth to spend that on place making and house building wouldn’t we? Why has planning turned into a regulatory service since 1979? Well look what’s happened in those 30 years, all the houses are sold off, back then we spent nothing on housing benefit and where does it principally go? Into the pockets of the landlords, it’s shocking.

“We’ve privatised all the utilities in that time which are now solely interested in their share price How on earth are we joining up transport when our railways and buses have been totally deregulated to the point where we don’t have any say over what they do other than subsiding them?”

Outlining the source of any potential solutions Reid looks to the escalating cost of land as a key factor in determining the ultimate affordability of property. To that end Reid calls for the adoption of a form of land corporation to assist local authorities in acquiring appropriate sites for development and service it to hand onto developers willing to meet our demands and standards.

Reid continued: “There are 2.5m houses in Scotland, you have to look after those because even if you could build more houses you still have to look after those we’ve got. The banks are the biggest stakeholders but they are not focussed on maintenance. Why aren’t they providing interest free loans to repair your roof or maintain a tenement? The answer is they’ve got too big a stake in the interest out of their mortgages to do that.

“If we do we’re going to end up with a generation of homelessness that we’ve not previously encountered. We have to get the government to commit to just do it.”

Summing up proceedings Alistair Scott, director of Smith Scott Mullan Associates and chair of the board of trustees at the Scottish Civic Trust, said: “We’ve heard a lot about process and there is room for improvement, land supply and the disjoint between the aspirations that we and government have and what actually gets delivered. I think Bob said what many of us have felt and said, the government must lead.

“We’ve heard a lot about house builders. They have a role in this, they are something we need. The problem is how do we engage them? I think we engage them in the wrong way at the moment. In other countries the government leads and the house builders come in behind that to build houses.

“We know what we need to do we just need the political goodwill to enforce it. As a group we’re not against development, we accept that development happens, what we are against is poor quality and inappropriate development. Particularly noticeable is the impact on small towns, you can add a building to a city and it doesn’t change its fundamental character. You can add to a small town and it does fundamentally alter that. Technology changes quickly and architectural fashions change quickly and people change more slowly.”

As delegates shuffled away facts and figures ringing in their ears the abiding sensation is one of powerlessness. With government unwilling or unable to act and developers and banks beholden to the bottom line the housing crisis looks set to rumble on for many years yet, the dream of a property owning democracy fading bit by bit as it does so.

|

|

Read next: Portsoy

Read previous: Scott Sutherland School of Architecture

Back to January 2016

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.