Ballantine Bo’ness

13 Jan 2016

Ballantine Bo’ness iron foundry has benefited from a recent revival of interest in craft skills, feeding demand for architectural castings. Here Mark Chalmers dons his heat visor to see first hand how this industrial stalwart is recasting itself for the 21st century.

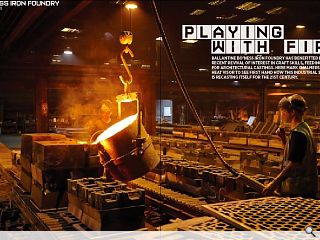

Iron founding begins around two in the afternoon, with a sheet of flame and showers of sparks. The furnace operator carefully tilts the Inductotherm furnace and a stream of molten iron pours into the ladle. At 1500 deg.C the iron gives off waves of light and white heat, sparks fly in every direction and orange flames leap upwards.The foundrymen are completely absorbed in the task. Despite their goggles, gauntlets and heavy boots, they handle hot iron using graceful and economical movements. The ladle crane carries the iron slowly, gently, towards a row of mould boxes set out on the bench. Using a geared wheel on the ladle, molten orange iron is poured into the first mould: blue flames shoot from the gates and the air is warped by waves of heat.

In a few hours, the liquid iron will cool and in due course find its way from the foundry at Bo’ness to Albert Bridge in Glasgow, which Ballantine Castings are currently refurbishing. Each casting is part of the bridge’s new balustrade and in total around 200 tons of iron will be cast, fettled, painted and erected over the Clyde during the course of the next few weeks.

The New Grange Foundry in Bo’ness embodies something of Scotland before the term “post-industrial” was coined. Industrial-scale iron making and founding began two-and-a-half centuries ago just a few miles from here, at the Carron Works in Stenhousemuir. It became the centre of the light casting industry, employing 8,000 people just on its own; around it grew up many more foundries, the sons and daughters of the Carron Company.

The Falkirk area once had over 100 iron foundries and a couple of generations ago, Scotland’s iron and steel trades employed 100,000 people. Alongside iron and steelworks like Ravenscraig, Dalzell, Clydebridge and Dalmarnock were iron founders such as Walter Macfarlane’s Saracen Foundry and George Smith’s Sun Foundry in Glasgow, the Lion Foundry in Kirkintilloch and the Carron Company.

Today, those great names are nothing more than industrial archaeology, yet iron founding is also a 21st century enterprise. Ballantine Castings use the precision of air-set casting to form components to a tolerance of 1mm. Coke-fired furnaces at Bo’ness have been replaced by an electric induction melting system, and thanks to the the science of metallurgy, sophisticated grades of ductile iron are available with none of the brittleness once associated with castings.

If the afternoon’s work at the New Grange Foundry looks dramatic, the morning is spent quietly preparing the patterns and moulds.

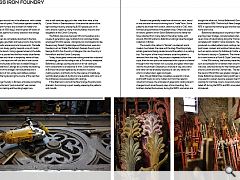

Patterns are generally made from aluminium, resin, wood or wax and are the mould-forming tool or “male” form. Some patterns are made from scratch, drawn by hand or CAD, then formed using softwood in the pattern shop. Others are copies of historic patterns which Gavin Ballantine and his father Ian have collected from many defunct foundries: today, with around 250,000 patterns, Ballantine Castings have the largest collection in Britain.

The mould is the pattern’s “female” counterpart and is made in two halves: the cope and the drag. Moulding simply entails greensand being packed around the pattern in a casting box. The imprint of the mould remains once the pattern is removed from the drag. The process is repeated to form the cope, then the two parts are assembled with a sprue or channel through which the molten iron is poured, and gates which lead into the mould itself. Greensand, a mixture of clay, silica sand and water can be endlessly recycled, as can any waste iron which is melted down again and again.

Even though Ballantines nowadays use electric cranes and forklift trucks to carry molten iron from their electric induction furnaces, the principles of greensand casting haven’t changed much since the early days of iron-founding. Two brothers started the business during the 1820’s, and when one bought the other out, Arthur Ballantine & Sons was formally established in 1856. The firm built New Grange Foundry during 1876: it opened the following year and has been Ballantines’ home ever since.

Ballantines developed an expertise in fabricating and erecting major bridges, complemented when the firm cast over seven miles of balustrading along the Thames Embankment, complete with “dolphin” lamp standards. The company also produced so-called pattern book castings: lamp standards, post boxes, cookers and window frames alongside one-offs such as replica cannon for Edinburgh Castle, and the clockface for Hoover’s factory in Clydebank. That travelled from Bo’ness to its new home on a Forth & Clyde Canal barge!

In the 20th century, the foundry made larger scale castings such as bulkheads for oil tankers then once the Great War was over, solid fuel stoves for the market garden glasshouses around Lanark and the Channel Isles. The decades following the Second World War saw greater changes in the foundry trade. Ballantines stopped making solid fuel ranges and stoves once electric cookers became popular, then their baseload of castings for manhole covers, rones and underground drainage tailed off during the 1970’s and 80’s once plastic pipework was introduced.

Ballantines merged with Bo’ness Iron Co in 1987, becoming Ballantine Bo’ness; the firm is now styled Ballantine Castings and is probably the largest jobbing iron foundry left in Scotland. The National Lottery’s Heritage Lottery Fund proved to be architectural iron-founding’s saviour during the 1990’s. It has funded the restoration by Ballantines of many historic structures, including Westminster Bridge in London, North Bridge in Edinburgh, and currently the Albert Bridge over the Clyde.

For architects, the foundry’s best-known work includes the restoration of the Ca d’Oro Building in Glasgow. The interior of the building and mansard roof were destroyed by a major fire in 1987, and although the cast iron frame survived, it was badly damaged. Two bays were completely reconstructed by Ballantines, and that led on to Murray & Dunlop’s £30m restoration of Central Station in Glasgow a few years later.

The station structure was originally supplied by Walter Macfarlane & Co’s Saracen Foundry, but that closed in 1967. Ballantines refurbished and replaced interior ironwork, the roof’s structural ironwork and the huge glazed gable. They also reconstructed the most impressive cast ironwork in Glasgow – the decorative porte-cochère at the Gordon Street entrance.

At the other end of the scale are gates and railings: Ballantines recently restored over two kilometres of railings in Baxter Park in Dundee and a similar run at Duthie Park in Aberdeen – the original iron railings were cut down with flame torches at the start of World War Two, so that the iron could be melted down for munitions. Ploughshares into swords, if you like.

Many believe that the main value of this exercise lay in propaganda, to make people believe they were contributing to the war effort, when in fact the railings were never used. Owners were not paid for the scrap value of the metal, but were offered timber fences instead. Some say that thousands of tons of scrap iron was eventually dumped at sea … although historians at the Imperial War Museum maintain that most of the railings were melted down and made into armoured vehicles.

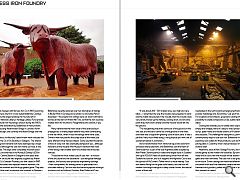

Those are the most visible uses of cast iron – a mixture of the structural and the decorative – but alongside heritage projects, the foundry also produces engineering castings – from components for railway points to gearboxes for a chocolate refinery. Cast iron has also become popular amongst sculptors such as Anthony Gormley, Alan Potter and Tony Cragg. In fact, after Cragg left art school, he worked in a foundry which cast electric motor components.

“It was about 200 - 300 metres long, very high and very black … I remember the way the moulds were prepared in sand and the metal was poured in the moulds, then the moulds were very slowly moved up the hallway, cooling down, and at some point they went over a shaker and the moulds would fall into the ground.

“The red glowing machines came out of the ground on the one side, and the sand came out of the ground on the other, and there was a huge ever-growing cone of black sand. It was a job that I very much liked doing, a very physical job with a lot of excitement about it, somehow…”

Iron’s transformation from white hot liquid into solid form embodies that excitement, and Ballantines cast the Heart of Stenhousemuir: a pair of life-size Highland cattle sculpted by Alan Potter. Stenhousemuir hosted the largest tryst in Scotland with up to 100,000 head of cattle being driven from all over Scotland to auction, and as it happens the Highland Coo is also the symbol of McCowan’s Toffee which is made nearby. Cast iron seems fitting for the great solid beasts, and the iron will mellow from bright orange to a deep conker brown, the natural colour of their pelt.

Cast iron is an expressive material, but there’s a risk that traditional techniques such as casting and forging are overlooked in the rush towards emerging technology such as powder metallurgy and 3D printing – yet each has its strengths. For sculptors and architects, greensand casting offers the possibility to create compound curves, subtle reliefs and fine detail.

Casting also enables you to create exact copies relatively simply and cheaply, hence it’s easy to mass produce the fleurs-de-lys, spear heads and thistle blooms of Victorian railings and balusters. The challenge for designers is, perhaps, to find contemporary ways to use cast iron. Ballantines have been exploring new outlets for their products, such as 800 cast iron paving slabs in Coventry which were embossed with designs in shallow relief.

Meantime, back at New Grange Foundry, the moulds smoke gently as the molten iron solidifies. By tomorrow the metal will be cool, then the moulds will be shaken out and the gates and risers removed. The cold iron is dull grey and rough to the touch. Some castings are machined afterwards for a smoother finish and finer tolerance; others are fettled with hammers and grinders, pelted with steel shot in a blast booth then painted or coated.

The end result is timeless, almost indestructible and testament to cast iron’s staying power.

|

|

Read next: Stoke-on-Trent: Pottering Along

Read previous: Charettes

Back to January 2016

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.