Seaside Remedies

20 Oct 2015

Chris Stewart of Collective Architecture investigates a recent renaissance in Britain’s traditional holiday resorts, spurred by the spectacular success of Banksy’s Dismaland, which has generated £20m for the economy of Weston-Super-Mare and Wayne Hemmingway’s Dreamland, Margate.

No place on earth has as much sea as Britain and no place in Britain has as much seaside as Argyll. Weaving in and out it has more coastline than all of South East England, dotted at intervals by the five towns of Campbeltown, Helensburgh, Oban, Rothesay and Dunoon; which combine in perfect harmony to form the funding acronym CHORD. Each dot on CHORD has received a share of £30 million, with both Rothesay and Dunoon choosing to rethink their ‘doon the water’ fun palaces; will they compliment or will they compete.The bygone era of UK industrial leisure has left these once glamorous destinations struggling with sorry family amusements, boarded up shops and rachmanian landlords advertising to encourage dole bound youths ‘why rot in a peripheral estate when you can enjoy a room with a view for the same pre paid rent’. Two years after the Office for National Statistics (ONS) announced that deprivation and poverty in coastal towns was far worse than the rest of the country, is there cause for optimism that this might change. In 2013 Visit Scotland report the highest visitor numbers to Scottish Beach Towns in almost a decade; why then in the same year did the Centre for Social Justice warn that seaside towns were stuck in a cycle of poverty and suffering ‘severe social breakdown’. Could the jewels of the Clyde ever shine once more.

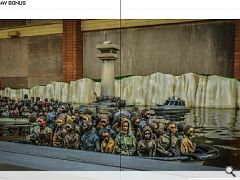

Experience shows one off catalysts will not offer a long term solution. The white elephants of national lottery madness such as Irvine Town’s Big Idea will keep feet on the ground. With a build cost of £14 million, the Big Idea set amongst the sand dunes, lasted just three years closing in September 2003 with debts in the region of £350,000. All employees lost their jobs and the impact is still felt. There is though serious evidence that culture led regeneration is turning a few South Eastern English beach towns around, with most recently Weston-super- Mare benefiting from Banksy’s Dismaland. A family theme park unsuitable for small children with a Jimmy Saville Punch and Judy show, a Cinderella crash scene and the Grim Reaper whooping it up on the dodgems. Tickets are sold out and the amusements include works by Damien Hurst, Jenny Holzer and Julia Burchill however whilst hipsters sup pop-up craft beer, Weston-super-Mare lido remains closed. Around the coast Hastings now enjoys the tag ‘Shoreditch on Sea’ and where the battle for the fire ravaged Hastings Pier soldiers on with silent discos and adopt a plank. Everyone played on this pier, from Jimi Hendrix to the Rolling Stones while the Queens Hall in Dunoon shared the experience hosting the likes of Pink Floyd and Blur.

The latest addition to Hastings has been the Jerwood Gallery by architects HAT Projects, described by Wallpaper as a perfectly formed, modest space that doesn’t try too hard and according to Observer architectural critic Rowan Moore is not embarrassed by the stuff and clobber around it, and does not embarrass them. The Hastings Bonfire Society held different views burning an effigy of the gallery in 2008 in protest at the gallery’s impact on the old fishing industry. Britain’s biggest beached fishing fleet despise the gallery which they see as one more nail into their precarious near extinct way of life.

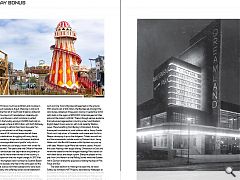

Likewise with its parachuted in Chipperfield Turner Contemporary, Margate is fast becoming the queen of seaside hip. Co-joined by the Javelin train to London with its endless supply of beards and pipes, its latest attraction is Wayne Hemingway’s determined effort to bring back Dreamland. For those not in the know, Dreamland is the oldest surviving amusement park in Great Britain and Wayne Hemingway together with his wife Geraldine are the retro design couple who founded Red or Dead; now determined to bring Dreamland back to the living. Crammed full of Brighton Rock Dodgem cars, Viking style boat swings, Scenic Railway Roller Coasters and a Wall of Death according to Wayne ‘we did not want to do a heritage theme for the 50s and 60s. It doesn’t feel 50s. It feels timelessly like the seaside, like a dream’.

What has Rothesay and Dunoon made of all these goings on, as luck would have it I was fortunate to join a small expedition made by a few of the fine folk of Bute on their field trip to Bexhill and the De La Warr Pavilion. The inspiration for James A Carrick, who designed Rothesay’s own Pavilion in 1938, the refurbishment of the De La Warr Pavilion has been a catalyst for the rejuvenation of Bexhill, a must trip to seek out ideas both architectural and economic. Despite its aristocratic veneer, being the brainchild of the 9th Earl De La Warr, Bexhill’s pavilion is an expression of a modernist social and moral agenda, transformed into an aesthetic philosophy. The Earl de La Warr was of course chair of the local Labour Party, the first hereditary peer to join the Labour Party and a government minister at 23 . It was therefore no surprise that the winning design was by two architects, Serge Chermayeff a Russian and the other, a refugee from Hilter’s Germany, the better known Erich Mendelsohn.

The De La Warr Pavillion was originally built in 1935 and refurbished in 2005 in the main to improve its fabulous hall but also to build in a flexible art gallery. It now attracts over 350,000 visitors per year and its recent success relies on the theory of Social Capital, the connections, networks and the partnerships which are generated. The core thesis of the social capital theory is ‘relationships matter’ not just the visitors but those who support the Pavilion with a stake in its funding, artistic, commercial and business partnerships. De la Warr therefore does not stand alone but is part of a broader picture, half the visitors are local. There is a real chance that Dunoon and Rothesay can set aside any rivalries, work together and replicate this approach; all enjoying the events both in Cowal and Bute.

The ultimate problem for Rothesay and Dunoon is that they were developed to cater to leisure time as a result of changes to workers’ rights towards the end of the Industrial Age, when tourism was something fresh. When the masses went to Spain, seaside towns collapsed and the ruins were as epic as any of those experienced at cotton mills or steelworks. Seaside towns will never go back to the future and domestic tourism will never play the dominant role it once did in shaping the local economy of Dunoon and Rothesay. Their new economies will be complex, how do you revalue existing assets and how do you refresh the ‘visitor offer’ while nurturing alternative growth sectors and industries.

Change perceptions, drive up skills and create jobs; economic solutions are not in themselves a panacea. Vulnerable households, a sense of stability to the more deprived neighbourhoods and the need to promote cohesion between different communities are just as essential. While a focus on a diverse economy is important, it still remains crucial to tackle manifestations of decline and carry out the improvements to Dunoon Queens Hall and Rothesay Pavillion. Some claim the revival is underway with a dribble of commuters, tickets for Waverley paddle steamer trips fully booked and the occasional profitable restaurant. In the hey day of the thirties Rothesay was the most visited seaside resort in the UK. Before then Firth of Clyde resorts were havens for the Victorian middle class, evident by the their tenements and grand villas. In the same way that Margate attempts to tempt the Shoreditch hipster and London commuter, Rothesay and Dunoon aim to lure the central belt arty type and the Glaswegian seeking a bargain home.

Rothesay will tackle its evidence of decline by refurbishing its Category A listed pavilion, creating a second performance space, a community venue, offering let-able office space, the essential improved cafe but most importantly a multi purpose exhibition space capable of attracting some of those no miracles here Turner Prize types from up the water. Dunoon will similarity up-cycle its Queen Hall, always a bit more municipal than a fun palace, with a soft play area, new public entrance, facilitates for Skills Development Scotland and most importantly a new public library. The new Queens Hall will be the show piece as part of a new public realm, redeveloped seafront and most hopefully a saved Victorian Pier.

Can art put new heart into seaside resorts and towns? Rothesay and to a lesser extent Dunoon seem set to follow this path worn by their English sisters. They all boast left behind remarkable architecture to help pave the way but will this be enough to revitalise a blighted economy. As property markets in Margate start to crash, I like to think our Firth of the Clyde is a bit different and encourage all the arty types to take a jaunt doon the water (in a year or two).

|

|

Read next: Engineering Survey: Building Boom

Read previous: Concrete Crusader: Angry Bird

Back to October 2015

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.