Manuel Brickworks

19 Oct 2015

Following the demise of Sir Tom Farmer’s bid to develop a new town on the site of Manuel Brickworks, Falkirk, Mark Chalmers pays a visit to what was the largest brickworks in Europe to pick over what has been lost in his pursuit of a clearer definition of the ephemeral concept of ‘sustainability’.

Received wisdom has it that we’re custodians of the built environment: we merely add another layer to history before we hand it on to the next generation.Property developers are different. They have the ability to destroy and remake communities, yet with the exception of John Ritblat and a handful of others, their names are unknown. Most developers are happy to retain that low profile; Sir Tom Farmer is an exception.

Morston Assets was founded by Tom Harrison and Tom Farmer, but Farmer’s name is the better known, especially in Scotland. He is still “Mr Kwik-Fit”, even though he sold his tyres and exhausts business to the Ford Motor Company 15 years ago. Morston Assets and its operating companies were in the property development business until December 2014, when they went into administration.

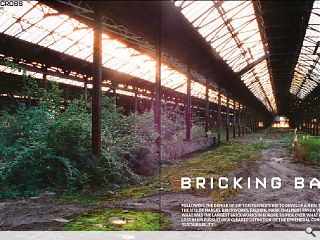

One of their largest projects was the redevelopment of a refractory brickworks called Manuel, which stood between Falkirk and Linlithgow. Manuel’s sheds formed a vast rectangle, one third of a mile on their long side. The Edinburgh-Glasgow railway runs to the north and the Union Canal bounds the site to the south-west; the ruin of Haining Castle stands at the north-western corner and the village of Whitecross lies off to the east.

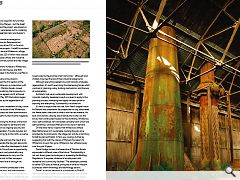

I visited Manuel Works many times. The first occasion was in 2002 while the brickworks’ guts were being ripped out, packed up and shipped to Poland. Several visits later came an autumn day in 2007 when Manuel’s rusty iron shell seemed to sink into a carpet of dead leaves. Curiosity brought me back again the following spring.

I parked at Muiravonside and walked along the Union Canal: the air was warm and still, birds sang and blossom hung in the trees. Shafts of sunlight shifted across the mossy floor of the brickworks, over one million square feet of it, and spidery shadows played over the roof trusses.

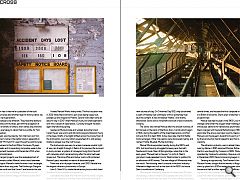

The brickworks was easy to access, because a public right of way ran straight through it. Relics of its previous life survived in dusty corners: a system of conveyors hung from the roof, with catwalks which remained long after the kilns had been ripped out. The time office and locker rooms still contained Manuel’s past, recorded on reams of discarded paper. There was a lot of paper because, until 2001, Manuel was the largest refractory brickworks in Europe.

John G. Stein & Co. made the refractory bricks which lined Scotland’s blast furnaces and gas retorts. Just before the Great War, the firm built the world’s largest brick kiln at Castlecary, and they were constantly hunting for new sources of clay. On Christmas Day 1923, they discovered a seam of fireclay near Linlithgow with an extremely high alumina content. It was christened “Nettle”, and shortly afterwards Steins sank a mineshaft and built a new brickworks close by.

The works was named Manuel after the ancient nunnery of Emmanuel on the bank of the River Avon. Construction began in 1928, during the depths of the Great Depression, and No.1 kiln was first lit in April 1930. A few days later, the first Nettle bricks emerged. Other clay seams were discovered nearby and named Thistle, Bluebell, Myrtle and Daisy.

Manuel Works expanded rapidly during the 1930’s and 40’s, but local housing struggled to keep pace. Kenneth Sanderson’s book, Stein of Bonnybridge, notes that in the early years “Manuel had no houses,” so John G. Stein’s grandson made repeated trips to Westminster to petition for an allocation of 80 homes. The new village of Whitecross was the result. Tied housing wasn’t unusual in the brick industry: Allandale village was built at the start of the 1920’s to house Stein’s workforce at Castlecary.

Manuel grew decade by decade until there were 20 acres of buildings, a labour force of 1200 people, and over 200,000 tons of bricks were fired each year. The works offices expanded several times, and housed the first computer to be installed in a British brickworks. Steins even wrote their own computer programmes!

Manuel reached its peak in the 1960’s, but fundamental change came when the oxygen steel-making process was introduced: demand for refractories plummeted. In reaction, Steins merged with General Refractories in 1967, then two years later the group was taken over by Hepworth Ceramics. Manuel won the Queen’s Award for Exports in 1987 although by then production had dropped to less than a quarter of its capacity.

The refractory industry was in retreat: Hepworth was taken over by Alpine in 1997, renamed Premier Refractories, then the firm was bought by Cookson in 1999. Manuel Works was operated by Cookson’s subsidiary Vesuvius until it finally closed in December 2001. Decommissioning began in the New Year.

Sensing an opportunity, Tom Farmer’s firm stepped in. Morston Assets bought the brickworks in August 2002, then drew up plans for a £150m redevelopment consisting of 1000 houses and half a million square feet of offices. Objectors argued that the proposals went against the intentions of the Local Plan: after much debate, planning approval was refused.

Morston regrouped and tried again. In 2006, they approached financial institutions to raise £1bn to fund their many brownfield projects, including Manuel – but the Great Recession came along in 2007 and the project was placed on hold. Meantime, the giant sheds were leased out to a catering firm, car repairers, a structural steel fabricator and builder’s merchant.

A couple of years later, the scheme re-emerged as a so-called SIRR or Special Initiative for Residential-led Regeneration, and joined the ranks of the SSCI or Scottish Sustainable Communities Initiative projects. Cadell2 formulated a masterplan joining the Manuel site and Whitecross village, which now ran to 1500 new houses, 225 of which were classed as “affordable”. The scheme included offices and industrial units, a science park campus, a primary school and new village centre.

The project represents a five-fold increase to Whitecross, which currently consists of around 340 houses and 800 people; despite that, it was allocated in the Falkirk Local Plan in January 2010.

In June 2010, Farmer’s company announced an architectural competition to lay out the first section of the site, which Malcolm Fraser’s practice won in conjunction with Stewart Milne Homes. In parallel, Morston Assets moved forward with the intention of demolishing the brickworks. In October 2010, the masterplan was agreed, and it achieved planning approval in principle in May 2011. Demolition began swiftly afterwards, but that’s as far as the regeneration of Manuel Works has gone.

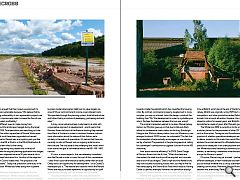

Four years later, Manuel remains a wasteland of clay, rubble and clinker. When asked about the future of the Whitecross regeneration, neither Morston Assets nor their administrators KPMG had got back to Urban Realm by the time the magazine went to press.

At this point, it’s worth examining the motives of the main players. Cookson were presumably keen to sell the land and rid themselves of its liabilities, such as ongoing security and maintenance, plus eventual remediation. The site includes old fireclay workings and former Haining tip to the north, as well as the former brickworks.

Morston Assets bought the site and took the role of land developer. They planned to remediate the site, gain approvals, construct infrastructure – then invite other developers to build out smaller parcels of land. Falkirk Council saw an opportunity for the regeneration of derelict land, and potentially many new jobs. By allowing a private developer to carry out the regeneration, they minimised the cost to their taxpayers, although they retained some control over it through the planning process.

The RIAS and Scottish Government contributed to the master-planning process at Whitecross, and both evidently viewed it as an exemplar project; in fact, the latter funded the Whitecross SSCI Design Competition. Adults in Whitecross saw the unhappy connotations of jobs lost at the refractory works swept away by the promise of jam tomorrow – although local children mourned the loss of their industrial playground.

Although everything appears to point towards wholesale regeneration, it’s worth examining the interleaving forces which constrain it: planning policy, funding mechanisms, and the lure of sustainability.

Architects look upon sustainable development with romantic credulity; developers see it as a lever to apply to the planning process; marketing men apply the description to anything and everything. Sustainability is a broad kirk.

It’s hard to dispute the fact that John Stein’s original vision for Manuel was sustainable. He prospected for clay, discovered the Nettle seam, then sank a mine to win the raw material. He built a brickworks close by, laid a railway line to ship out the bricks, then constructed houses for the workforce. Whitecross was a self-contained, rail-connected company town which was self-sustaining – provided Manuel’s bricks were in demand.

On the other hand, it seems that Whitecross without Stein Refractories isn’t sustainable. Lacking the jobs once provided by the brickworks, the village can only be a dormitory for Edinburgh and Falkirk. In fact, you could go further by suggesting that with the closure of Manuel, the reason for Whitecross to exist has gone. Whitecross has withered away over the past 14 years.

David Dodge, former chief executive of Morston Assets, expounded a different view of the future. “Sustainability is not just about green technologies or exceeding the Building Regulations. It requires a balance of employment with residential and community facilities.” The developer planned to deliver 1200 jobs at Manuel, principally in small to medium businesses within the energy and technology sectors.

There’s a narrow definition of sustainability in PAN 83, which speaks about enhancing the site’s natural environment and resource efficiency. However, development also needs to sustain jobs, local heritage, and the existing way of life. Morston Assets argued that their mixed-use approach to regeneration was sustainable because, “We believe that by fully embracing sustainability in our regeneration projects we preserve value, improve sales rates, increase the flow of new projects and protect profitability.”

There are different ways to make money from regeneration, but the landscape changed during the Great Recession of 2008. Total demolition and rebuilding isn’t the only solution. The million square feet of Manuel Works were dilapidated, but could have been upgraded and reused. One obvious use for Manuel was as a logistics park, just like Centrelink 5 on the M8 at Shotts, or the M8J4 Distribution & Business Park a few miles further along.

However, upgrading was passed over in favour of demolition. When the original planning application was lodged, one of the tenants objected because 50 jobs were at risk in the structural steel fabrication firm. Another of the objectors’ letters to Falkirk Council stated that, “the proposal is not economically viable”. Sadly, that prediction came true, in the sense that Morston Whitecross failed along with its parent company.

Was the Whitecross masterplan unviable? Was the developer too ambitious? Morston Assets’ website stated, “We operate a traditional and conservative investor developer business model where senior debt loan to value targets are around 50 per cent and tenant income covers interest costs. We speculate through the planning system, build infrastructure and follow that by a mixture of developing, partnering and land sales.”

A truly conservative business model seems at odds with a speculative approach to development – and it seems that Morston Assets fell short of the financial backing they needed from Bank of Scotland in order to continue. However, without more information about the nature of their failure, we’re similarly in the realms of speculation. It’s certain that there are currently no jobs at Manuel, and no ongoing rental income from the site. The only asset is the underlying land value, which is low due to the glut of commercial land in the M8 - M9 - M80 corridor.

It’s true, in some respects, that we redevelop brownfield sites like Manuel in order to cover the cost of their remediation – sites which could otherwise be a liability rather than an asset. Cheap land is an opportunity for development – or as Cadell2’s masterplan put it, “The relative land value for which the Manuel Works site was purchased represents an opportunity for uplift when phased housing sites are released into the market.”

Housing development is attractive because the returns are high and relatively quick, stoked by the never-ending trend towards smaller households which has magnified the housing crisis. By contrast, commercial property development is more complex: you sign up a tenant, tailor the design, construct the building, then “flip” the development in order to crystallise your return. Perhaps the balance between the two was wrong?

The original masterplan aspired to re-open Manuel railway station, but Morston gave up on that due to Network Rail’s refusal to countenance a new station on the busy Edinburgh-Glasgow line. With no railway station, how can Whitecross, now enlarged to almost 2000 houses, be sustainable? The fact that the masterplan scheme actually encourages car use is borne out by a Section 75 agreement in the planning approval, calling for a developer’s contribution to upgrade Junction 4 on the M9 motorway.

How about resource efficiency? In 2009, David Dodge of Morston Assets told the AJ that, “When the sheds are dismantled, the steel structure will be recycled, and concrete and bricks will be salvaged.” Stein’s high-alumina Nettle bricks may not be suited to building houses with, but they’re fine for hard landscaping: the Yellow Brick Road which leads to Haining Castle is a perfect example. However, the demolition arisings consist of millions of broken bricks, most likely fit only for upfill.

Another lost opportunity was saving the area’s industrial heritage. A couple of miles north of Whitecross is the fireclay mine at Birkhill, which lies at the end of the Bo’ness steam railway. Birkhill was originally run by P&M Hurll, one of Stein’s competitors, and when production ended Falkirk Council turned it into a tourist attraction. However, the mine has been closed to visitors for several years, and Birkhill’s clay mills were demolished a couple of years after Manuel’s giant sheds.

The Whitecross SIRR is currently in limbo, and provides a salutary lesson for the promoters of other SSCI schemes such as Knockroon, Tornagrain and Grandhome. It raises the question of whether speculative developers are equipped to deliver projects on this scale. How would Morston Assets address the unmet demand for affordable housing, or the pressure to create jobs in an unemployment blackspot? How can Whitecross avoid becoming a dormitory suburb for car-owners, or remaining a wasteland while the administrators seek a buyer for Morston’s assets?

Of course, Manuel may yet succeed – perhaps with a different developer, a fresh masterplan and new funders – but you do wonder whether this is a truly sustainable route to creating communities. Meantime, Manuel Works’ destruction saddens me, even today. Partly because it was in vain, and more so because no-one will ever be able to explore the ruin of Europe’s largest brickworks, like I did on that fine spring morning in 2008.

|

|

Read next: Ronald McDonald House: Home From Home

Read previous: HES: Power of Two

Back to October 2015

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.