Eric Parry: Lost Streets

15 Jul 2015

Fresh from publication of his new book looking at the importance of context Urban Realm spoke to London architect Eric Parry to discuss the importance of context in design and whether we’ve lost the ability to build streets. Might the new London vernacular herald a return to no-nonsense architecture?

A global arms race for recognition is seeing many architects choosing to disregard the subtle charms of background ‘wallpaper’ buildings in favour of the brash one-upmanship of icons and set-piece statements. In his new book, Context: Architecture and the Genius of Place, architect Eric Parry rails against this form of physical isolationism by urging practitioners and students to demonstrate how context can inspire design. As one of London’s most eminent architects Parry is well placed to argue for a more dynamic response to setting that doesn’t meekly kowtow to what has gone before.Asked if we are witnessing a counter-reaction to the excesses of icon-itis, Parry told Urban Realm: “Not so much icon-itis but there is a mistrust of buildings which try to stand autonomously when they’re not an absolutely unique stand-out monumental building that means a lot to a culture in terms of its condition as something sacred, such as a museum or major concert venue.

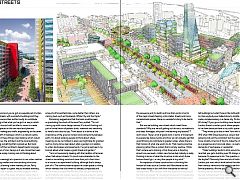

“Certainly here in London there is a profusion of these taller buildings that just don’t know how to meet the ground, we need more residential, amenity and community space but buildings are designed in an absence of proactive planning that creates constraints in which architects can sensibly work to achieve something that is greater than the sum of its parts - like a street!”

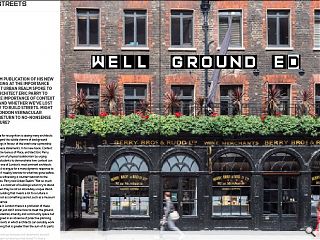

We used to throw up terraces and tenements around the country but seem to have lost that knack? Is that a skill we need to re-learn? “I think it is actually, walk around Glasgow or Liverpool and you’ve got an exquisite set of urban experiences and streets with wonderful buildings and they don’t have to pronounce their author loudly to contribute mightily. The thing is that what you’ve got is a way in which polarity has come to exist with architects sworn to create individual masterpieces on th

e one hand and planners involved in policy making and traffic engineering on the other.

“There’s a dearth in-between which is a natural centre point around which these things could balance which would be the urban planner, the architect and the local authority somehow creating something that is joined up. But local authorities got rid of their architects departments long ago. Maybe the business of civic design as it was coined has been downgraded. It’s a sorely missing core to thinking about cities.”

With space increasingly at a premium in our urban centres plots are becoming smaller and more existing structures are being re-used, allowing a new intensity of use. Parry observed: “Urban repair is a great way to recreate intensity; it’s also to do with use in streets and what happens in the background in terms of the public dimension rather than it simply being a front door to a terraced house - which we can’t really afford now in terms of space. On the other hand huge amounts of brownfield sites, some better than others, are coming back such as Docklands, White City and the Clyde.”

Dismissing suggestions that the book could be seen as precluding the shock of the new Parry added: “I’m not coming up with a new design manual. It’s about thinking not just in formal terms of pattern book, materials and sensitivity to what’s next door to you. Think about it in terms of the importance of the ground, horizon and connectivity between parts. It’s about wasking people to think about where meaning can be re-instilled in areas we might take for granted such as trying to be clear about what a garden is in relation to urban landscapes and pavements. I’ve got a real bee in my bonnet about what makes a good street and garden.”

“I am not necessarily dealing with the tradition of terraces when I talk about streets, I’m much more interested in the street as something social and more than just a front door to a house or an apartment building, although that’s always part of it. The communicative aspect of urban space is a thing which interests me a lot when its densely compacted and how it works in a place like Mumbai. How on can rekindle the spirit of blocks and streets, reducing massive areas for service and dead frontage? I’m very excited by what it is that actually contribute in the passage along a street, both in terms of the sequence and its depth and how that works in terms of the major streets feeding into smaller streets and more conspiratorial spaces, there is a wonderful story to be had in that.”

But are we building new streets which meet these standards? Why are we still getting cul-de-sacs, roundabouts and dead frontages, why aren’t we learning any lessons? “I don’t know. There’s a lot of good work in terms of movement by people like Space Syntax and how we can actually get that good thinking to contribute to greater scales where there is that horizon of what one wants to do. That means proactive planning rather than a system that is simply reactive. I think that’s where we’re missing a trick. Everyone is shouting about how we need x million new homes but nobody is really thinking in terms of what the structure is into which those homes should go – or very few people in my mind.”

An explosion of tower construction is shrinking the horizon of cities such as London and Manchester as we lose broad vistas in our shift from horizontal to vertical development. Who decides what the skyline of a city should be? Parry answered: “It’s amazing how quickly it’s happening. There are 350 buildings overt 20 storeys from the last count here in London, it’s an interesting anarchy. It’s not just the tall buildings but what those in the tall buildings look down on. Has anybody ever talked about a middle horizon which is also complementary in a dense city, 15 storeys rather than 40 storey? If you go on building more densely in the City of London there’s a certain point where people just don’t want to be there because there is no public space and no amenity.

“They woke up to that in new York with the ordnances of 1916 when Wall Street became a canyon but we’re a bit slow in grasping not just the constraint but the opportunity to think more broadly in terms of how to make the city more liveable as a gregarious and convivial place - as well as meeting the demands of workspace or residential.

“Taller buildings tends to stick around longest, it’s very rare that you get a building over 20 storeys pulled down because it’s expensive to do. The question is who is designing the skyline? Obviously there are lots of buildings being built in London just now which skulk behind the shadow of St Pauls from various views and that tends to be the criteria for their formal presence. Are the public admitted to the top of the building without booking this that or the other? How does the top manifest itself? It’s a vexed question and needs to be considered more holistically I don’t think any individual has the answer.

“We have a skyline that was very much developed here during the mayorship of Ken Livingstone with Richard Rogers and others but the scrutiny of it in advance is incredibly important and I just don’t know how in a democratic condition that is decided. Is there a forum where one can debate in intense ways what the skyline means, I don’t think that forum is available.”

Is there a counterargument that actually London thrives on this cacophony of styles and the jumble of buildings… is this chaos its strength allowing the city to innovate whilst others such as Paris, with less room to breathe, stagnate? “London is a city of cities. I think Haussmann is really interesting, you can’t imagine Haussmann happening without the pre-existing medieval fabric but it’s still about as good as it gets in terms of streetscape. Paris is still wonderful with hundreds of kilometres of wide roads and enough pavements to spill out their cafes. There’s a good role model there although I’m not suggesting repeating it in London, although others have tried.”

What’s your stance on the New London Vernacular? Can it raise standards, or is it just lazy and stifling? ”Brick can be wonderful but it does need to be judiciously used. Is it a new vernacular? It’s fine and higher is fine but what is important is it’s not just the front it’s how you find an interior beyond the street to which taller buildings work so they’re not just an object to walk around. It’s not just a gated entrance, there is some porosity and there is a way of drawing a more complex whole maybe into urban blocks - Something that is part-street but has a greater scale to it would be interesting.

“I don’t think the Olympic Village got it right but there was something about eight storeys and what that means and an interior that is shared although it could have been much more generous and more interesting. It could be an answer with more variety of materials but it comes down to how the piece fits within the jigsaw.”

“I think the book has good lessons to draw attention to which allow people to think again about what has been successful and good in order to think about what may be successful and good.”

With Britain requiring an unprecedented volume of housing and infrastructure just to regain ground lost to years of inertia there has never been a more urgent need to re-think how our cities are organised and built. The recession was an opportunity lost but with the economy showing signs of life it is imperative that we get to grips with this challenge or we are forever destined to repeat the mistakes of the past.

|

|

Read next: Byker Wall: Colour Bind

Read previous: Planning: Turf War

Back to July 2015

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.