Tower Blocks

15 Apr 2015

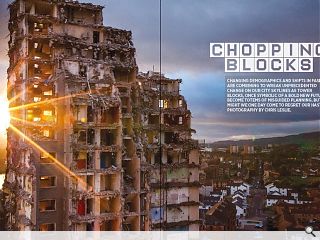

Changing demographics and shifts in fashion are combining to wreak unprecedented change on our city skylines as tower blocks, once symbolic of a bold new future, become totems of misguided planning. But might we one day come to regret our haste? Photography by Chris Leslie.

Edinburgh College of Art’s move to launch a digital archive of British tower blocks, curated by Miles Glendinning and financed by the Heritage Lottery Fund, comes at a critical moment in the history of the typology, with demolitions now taking place almost as quickly as they were built. The Tower Blocks – Our Blocks will see 3,500 photographs from the 1980s digitised documenting estates ranging from Glasgow’s iconic Red Road to the Barbican in London.Asked to describe the goals behind his pet project Glendinning told Urban Realm: “These images show people’s lives in everyday environments, many of which have since been demolished. We had an intuitive feeling that local communities have generally been more positive about these environments and we think there could well be a lot of interest in it.” That said Glendinning is well aware of the dangers of over romanticising, acknowledging that it would be ‘a bit tricky’ to apply the language the style of language more commonly associated with country houses or 19th century buildings. “They are still a bit controversial, so I think recording is more important than trying to preserve,” Glendinning concludes.

Whilst the first phase will take the form of a simple archive Glendinning hopes that later phases will involve local communities and he is already working with local communities in Wester Hailes, Wolverhampton and Birmingham to make it more interactive. In other words housing typologies are nor black and white or good versus bad but grey, so to speak. Glendinning remarked: “One of the problems with discussing housing types in Britain and to some extent the United States, is the culture of extreme opinions. They’re either very, very good or very, very bad. The idea that you should put them all up or pull them all down can lead to wasteful solutions.

“Refurbishment would be prudent if possible given the affordability issue, the difficulty being the high land costs driving all this, which is a global phenomenon. It is difficult to see how any individual nation state or national authority would be able to tackle the problem. It would make sense to build at higher densities to try and get round this but the property ownership and house price speculation has gone so far that I don’t think even building at the densities of the 1950s and 60s, which are probably about the maximum that would be culturally acceptable, would be enough to tackle affordability. I think you’d need to build at a Hong Kong scale which would be ruled out by people’s prejudices and preconceptions. Living in standard social housing blocks of 41 storeys up to 800 flats in a block has some benefits of accessibility to community and commercial services.

“Private developments seem superficially very different. They seem to be laid out for show with a gestural feature whereas public housing was about having standards you applied evenly throughout the development. I don’t find the approach of show blocks very attractive with the glitzy marble finishes and bronze windows but that’s just my personal view.”

Acknowledging that in the Prince Charles era of ‘monstrous carbuncles’ anyone saying concrete buildings are nice and brutalism is good would have been laughed out the room Glendinning believes attitudes are beginning to soften following an intellectual shift led by authors such as Owen Hatherley. Glendinning doesn’t believe such sentiments are limited to the intelligentsia either, pointing to anecdotal observations of his own that local communities are becoming interested. “We have a group in Wester Hailes called Our Place in Time led by Euan Howard. There’s a lot of public interest and a huge amount of recording of the built environment and heritage there.”

Mindful of the scale of transformation presently being wrought around us Glendinning believes we’re in the midst of an ‘era of transition’ akin to past frenzies familiar to those longer in tooth. Rather like everyone in the 1960s and 70s accepted that 19th century tenements and houses looked horrible, were built by a horrible system and should be demolished. By the end of the seventies almost everybody, including the inhabitants themselves, recognised that they were nice, symbolised community and should be preserved and rehabilitated. The course of tower blocks may be slightly different in the way it will happen but it will stay on the same trajectory.”

Despite all this Glendinning doesn’t believe that tower blocks have failed, labelling such a narrative as counterproductive. He said: “They became very unpopular with many inhabitants and opinion formers but I think the whole idea of discussing housing types in terms of success or failure is part of the problem rather than part of the solution.” That said, he is no advocate for the opposite extreme of listing and conservation either. “Public patience would start running out if you started listing housing projects, it’s an elite type of conservation devised for churches and country houses,” he noted.

At the forefront of the current wave of demolitions is documentary filmmaker and photographer Chris Leslie who has been tracking the demise of public housing for the past seven years from behind his lens. Leslie remarked: “Glasgow Renaissance comes from a term the city council used in 2006 when they said that Glasgow is going to undergo a renaissance, the skyline was going to be transformed and they weren’t going to repeat the mistakes of the past. It is a campaign they’re heavily pushing.”

This work chimed with Leslie, who’d spent a good deal of time in the Balkans. “I spent a lot of time in my early twenties in Sarajevo just after the war ended; it was a compact city of high rise flats, very eastern bloc in style. For me that’s what got me interested in the built environment, there are many buildings in Glasgow that are so run down that they could be on a front line in many ways.”

Commenting on the biggest and most controversial estate, Red Road, Leslie added: “The buildings themselves are iconic; to be in that exposed state for so long is really interesting. It’s just amazing to be alive at this time when you can witness it all happening. There are whole areas of Glasgow which have been completely transformed in seven years, that’s quite an incredible thing to think about.

“Yes, a lot of these places are run down, terrible places to live with people having a miserable existence for the past twenty odd years but a lot of that is down to management. There are a lot of residents I speak to who think high rise flats have a shelf life of about 40 years, they are just so demonised at that point that they have to go but a lot of them with a wee bit of imagination perhaps could stay. We have a housing shortage in the UK; it just seems crazy to demolish these flats.

“The difficulty is that these buildings are in areas where the problems are so endemic that the only alternative is to blow them up and have a big celebration on the front of the Evening Times about it. It’s sad that it’s come to that, because it should never have got to this point.

“Market forces encourage new build and a knock them down build them up again approach as part of the economy but you wouldn’t have residents of the west end or more affluent areas being shifted every 40 years, Glasgow’s always on this generational cycle. There’s never any end game, is it just going to keep going? It will be interesting to see if the houses we’re building now will still be there in another 30 years. It seems to be a really brutal approach as regardless of where you live its people’s homes and memories.

“A lot of people are tarred with the same brush so if you’re from flats that have a bad reputation you had to get out. But that’s where they were brought up, that’s where they knew, even if it was a very different place from when they moved in. I’ve spoken to a lot of people who have moved and they now have front and back gardens and they’re delighted with their new homes, there is a positive side to it as well of course and people are in better accommodation now and happier.

“The way high-rises have been demonised by the city council and the press certainly doesn’t help matters. The city has lost something like a quarter of its high rise flats since 2006 but you only have to look around to see how many people are still housed in those flats. What kind of message does that give to see them brought down and told they’re no longer fit for purpose?”

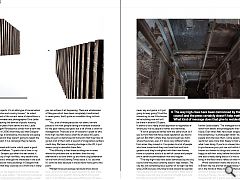

Taking parallels with the Bosnian front line a step further Leslie added: “I’ve managed to track residents down from letters and photographs that I’d found in their house. Even when flats have been stripped you always find something. I’d photograph what I found, find these people and interview them. Some people found it a bit weird but were more than happy to talk when I told them what I was doing. If you’re in a tower block no-one speaks to you because your just one unit within this large block known as a haven for drugs and crime so people are quite happy to tell their story before the building is gone. No-one else is really doing that so it’s nice to give the people living in the flats time to reflect on their history within it.”

Whilst demolition marks the end of a physical era in Britain the rise and fall of multi-storey housing lives on in the minds of those who lived there and, now, in an archive of images which document the highs and the lows of living in the sky. You can’t throw your pieces from a 20 storey flat, but it seems your 20 storey flat can go to pieces.

|

|

Read next: Murphy House: Tight Squeeze

Read previous: Diverless Cars: Highway to Hal

Back to April 2015

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.