Royal High School

15 Apr 2015

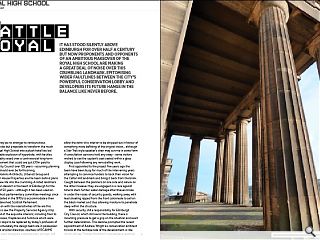

It has stood silently above Edinburgh for over half a century but now proponents and opponents of an ambitious makeover of the Royal High Hchool are making a great deal of noise over this crumbling landmark. Epitomising wider faultlines between the city’s powerful conservation lobby and developers its future hangs in the balance like never before.

Edinburgh may be no stranger to rambunctious planning battles but proposals to transform the much admired Royal High School into a plush hotel has led to a predictable explosion of hyperbole, with hackles understandably raised over a controversial long-term lease arrangement that could see just £10m paid to Edinburgh City Council over 125 years – assuming planning permission should ever be forthcoming.Gareth Hoskins Architects, Urbanist Group and Duddingston House Properties are the team behind plans to breathe new life into the crumbling A-listed landmark which has lain derelict in the heart of Edinburgh for the better part of 50 years – although it has been used on occasion to host parliamentary committee meetings since it was remodelled in the 1970s to accommodate a then anticipated devolved Scottish Parliament.

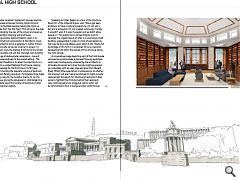

In common with the insensitivities of the era this brutal process saw the Property Services Agency strip out almost all of the exquisite interiors; including floor to ceiling bookcases, fireplaces and furniture which were carted out in skips to be replaced by today’s profusion of pitch pine. Fortunately the design team are in possession of Hamilton’s original drawings, courtesy of RCAHMS which, when read alongside contemporary surveys, will allow the retro-chic interior to be stripped out in favour of something more befitting of the original vision… although a Star Trek style speaker’s chair may survive in some form if consultation opinions hold any sway - some visitors wished to see the captain’s seat sealed within a glass display case following any remodelling work.

First appointed to the project five years ago the team have been busy for much of the intervening years attempting to convince funders to back their vision for the Calton Hill landmark and bring it back from the brink. Caught between the planners on one side and nature on the other however they are engaged in a race against time to stem further water damage after thieves broke in under the noses of security guards, walking away with lead sheeting ripped from the front colonnade to sell on the black market and thus allowing moisture to penetrate deep within the structure.

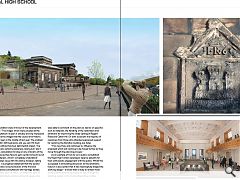

With security still a responsibility for Edinburgh City Council, which still owns the building, there is mounting pressure to get a grip on the situation and avert further deterioration. This decline prompted the recent appointment of Andrew Wright as conservation architect to look at the heritage side of the development, a role which will see Thomas Hamilton’s masterpiece restored for use as a hotel reception, restaurant, lounges and bar with two principal entrances fronting Calton Hill and Regent Road to facilitate people making the climb up Jacob’s Ladder from the Old Town. This will serve the dual purpose of activating the rear of the school and open up an original Hamilton retaining wall and tower.

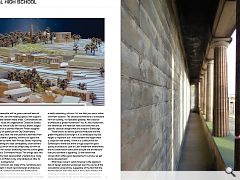

The driving premise behind Hoskins’ vision is to retain the symmetrical composition of Hamilton’s vision, originally intended to act as a gateway to Calton Hill but which has, ironically, served as a barrier to access. To heap irony upon irony the blanket A-listing for the school grounds incorporates not just the intended main building but also a range of dubious later extensions – none of which contribute positively to the overall setting. The chosen solution therefore is to retain the main block in a manner akin to a curated National Trust house, making it publicly accessible for the first time in its 190 year history whilst shunting the requisite volume of bedroom spaces into twin flanking pavilions. Fortunately three hotel operators are vying for the lucrative license to run the exclusive venue, giving the developers a vital bargaining chip to negotiate down the number of bedrooms whilst maintaining financial viability.

Speaking to Urban Realm on a tour of the structure David Orr of the Urbanist Group, said: “We’ve got keen ambitions to have a cultural programme, it’s not just a bar and a restaurant. It’s not a gated community, frankly it wouldn’t work if it wasn’t popular and we didn’t allow people in.” This public focus will see Hoskins work to reinstate the original layout of what is a surprisingly small building, exaggerated in scale in a trick of perception by the huge terrace and plateau upon which it sits. Taking full advantage of this form it is proposed to bury a spa and banqueting hall within the bowels of this structure below the main temple.

A provocative image depicting part of the front facade removed to accommodate a stairwell through sandstone vaults was mischievously prepared by the architects to stimulate discussion as to how the site might be opened up, potentially with an open step entrance from Regent Road. Whilst little expectation is harboured as to whether this prospect will ever being sanctioned (it might provide replacement stonework for discoloured sections) it does serve to highlight the thinking behind their approach. Less controversially two octagonal rooms within will be refurbished to form a lounge and bar whilst former classrooms meanwhile will be given a second lease of life as restaurant, bar and meeting spaces with support services located beneath these areas. Conversations are ongoing with visual arts organisation Collective Gallery to integrate the school fully with various events staged on the hill such as a planned Malcolm Fraser designed contemporary art gallery at the City Observatory.

Another hairy fault line with planners stemmed from the desire to create a ‘gateway’ entrance to signal the route up the hill to traffic from Princes Street, improving the current setting of a dual carriageway, crash barriers and bus laybys which will all be swept away to form an arrivals space for visitors stretching from the school gates to Thomas Tait’s St Andrews House. This brings back into use a kink in the road, necessitated originally by a rocky mound known as Millers Crag, only blasted out later to make way for a playground.

Repeated criticism was made of the ‘sandstone box’ aesthetic evident in much new Edinburgh architecture but Euan Leitch, spokesperson for the Architectural Heritage Society of Scotland, dismisses such concerns: “Georgian buildings were sandstone clad boxes, I find that a really interesting criticism. It’s one that you see in online comment sections. The classical architecture is a standard form of building, it’s replicated globally. Was classical architecture a global movement? Yes. As was modernism, the differences are materials were local and there are specific classical designs that are unique to Edinburgh.

“Restrictions do lead to good architecture and the great thing about Edinburgh is it’s a landscape city and height is important but I think beneath the height there is scope for real variety. I think it is a difficult line for Edinburgh to travel but there is huge scope for good quality architecture. Look at Leith waterfront where there are no conservation restrictions and yet the architecture that you see there is appalling. So the notion that conservation stifles good development is wrong, we get worse development.”

What does concern Leitch however is the apparent lack of design evolution evidenced over the course of the consultation programme, suggestive of the fact that the finished design may have been a done deal. A factor not aided by a weighted response form which allowed the team to claim that 79 per cent of 580 people to attend the first consultation were in favour of the development. Leitch added: “The images which were unveiled at the second consultation I’d seen in January and my impression is that they are the images that the council and Historic Scotland had seen in the middle of last year. The problem is you need 150 -200 bedrooms and you can’t fit them onto the site without having a detrimental impact. The consultation was certainly awareness raising but I don’t think it was a consultation to take on any criticisms of the proposal because they have to get a certain amount out of the site as hoteliers, which I completely understand.”

Hoskins takes issue with this stance however, telling Urban Realm in a prepared statement that the second consultation was a direct evolution of the first and followed extensive consultations with heritage bodies.

The architect said: “In March, a further two days of consultation attracted a similar number of people who were able to comment on the plans as well as on specifics such as materials, the handling of the restoration and ambitions for improving the wider setting of Regent Road and Calton Hill. On both occasions the majority of responses from those who attended expressed support for restoring the Hamilton building as a hotel.

“This input has, and continues to, influence the proposals which will continue to be honed further as they move through the planning process.”

As an example of how to run a public consultation the Royal High School developers deserve plaudits for their enthusiastic engagement with the public. Whilst this succeeded in stimulating discussion on the landmarks future it is less certain that it has meaningfully shaped the evolving design – a factor that is likely to remain moot as the scheme laboriously wends its way through the planning system in this most conservative of cities.

|

|

Read next: Kirkcaldy: Flour Power

Read previous: St Andrew Square:Lane Gain

Back to April 2015

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.