The Sublime in Scottish Art & Architecture

29 Oct 2014

From a vantage straddling art and architecture Paul Stallan delivers his thoughts on how we can shake free of preconceived notions of beauty to differentiate between the genuinely ugly and merely under appreciated. Is beauty ever universal?

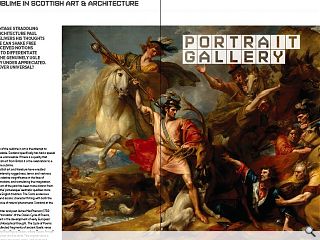

Historically Scottish art and literature have wrestled with ideas of awe, intensity ruggedness, terror, and vastness emphasising Man’s relative insignificance in the face of Nature, arousing emotions, and stimulating the imagination. Romantic Scottish art of the past has been more distinct from the ‘beautiful’ and the ‘picturesque’ aesthetic qualities more associated with the English tradition. The Scots evidence a more apocalyptic and laconic character flirting with both the grandeur and violence of natural phenomena; Scotland at the edge of the world.

The Scottish writer and poet James MacPherson (1736-96) known, as the ‘translator’ of the Ossian Cycle of Poems, was a key proponent in the development of early European Romanticism and philosophical thought. The Cycle of Poems were, essentially collected fragments of ancient Gaelic verse that promote the mythical figure Ossian, where Ossian himself relates the stories when old and blind. The original verse is imaginatively translated into poetic prose, with short and simple sentences to create an epic mood.

Clearly inspired by Scotland, MacPherson’s poems, became an incredible international phenomenon at the time. The work presents an ancient people living in a world of endless battles and unhappy love where characters are given to killing loved ones by mistake, and dying of grief, or of joy. Little information is given on the religion, culture or society of the characters, and buildings are hardly mentioned. It is said that the landscapes described are more real than the people who inhabit it. ‘Drowned in eternal mist, illuminated by a decrepit sun or by ephemeral meteors, it is a world of greyness’.

The impact of MacPhersons works globally and its celebration of sublimity in nature where Scotland is an unknowable wilderness where noble savages roam cannot be underestimated. From Napoleon to Thomas Jefferson to Voltaire and Walter Scot new narratives and imaginings emerged from MacPhersons writing. European composers like Schubert and Mendelssohn were inspired to visit Scotland in an attempt to capture the country’s sublime quality. Mendelssohn even visiting the Hebrides to compose the Hebridean Overture or Fingal’s Cave as it is better known.

The sublime in art is not exclusive to Scotland far from it. The theory of the sublime has been explored across many cultures. It was especially studied in the eighteenth-century across Britain, mainly because of the increasing importance of landscape as a subject category for artists and critics of the time. The Irishman Edmund Burke wrote a text in 1757 called ‘A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful’, which broke the idea of the sublime down into seven aspects, all of which he argued were discernible in the natural world and in natural phenomena. These aspects he listed as follows:

Darkness – which constrains the sense of sight

(primary among the five senses)

Obscurity – which confuses judgment

Privation (or deprivation) – since pain is more powerful

than pleasure

Vastness – which is beyond comprehension

Magnificence – in the face of which we are in awe

Loudness – which overwhelms us

Suddenness – which shocks our sensibilities to the point of disablement

A short descriptive text that I wrote in my sketchbook as a student and which I like to reference captures perfectly the ambitions of the artist and their compositional preoccupations with the sublime. The writing by Thomas Whately, in his 1770 Observations on Modern Gardening, praises the sublime effects in landscape gardening, advising designers that: “A little inclination towards melancholy is generally acceptable, at least to the exclusion of all gaiety,; and beyond that point, so far as to throw just a tinge of gloom upon the scene. For this purpose, the objects whose colour is obscure should be preferred; and those which are too bright may be thrown into shadow; the wood may be thickened, and the dark greens abound in it; if it is necessarily thin, yews and shabby firs should be scattered about it; and sometimes, to shew a withering or a dead tree, it may for a pace be cleared entirely away.”

Artists of the 1800’s who wished to achieve sublime effects did so through the heightening of nature’s mystery by presenting extremes in their work whether in height or shadow, steepness or distance or similar. A sublime work of the time was thought of as a simultaneous representation and awareness of both beauty and the grotesque, or the feeling of intrigue and terror, respectively, a sensibility artist’s continue to explore.

Romanticism of this period concerned itself with ‘intense emotion as an authentic source of aesthetic experience’. Certainly the wild landscape and seascapes of Scotland provided the ideal contexts for Scots artists like Alexander Nasmyth (1758-1840) to explore or English artist Turner (1775 – 1851), who both to quote the Whately text above, certainly showed ‘a little inclination towards melancholy’ in their work through the representation of darkness, obscurity, vastness and magnificence. “It is through obscurity of language that poetry incites the imagination ”wrote Burke in the 1700’s.

Not surprising creative tensions existed between Scottish Romanticism and the developing philosophies of the Scottish Enlightenment at this time, the later being more interested in the scientific rationalisation of nature rather than its meaning or emotive character. By driving British industrialisation the great thinkers of the Enlightenment might have eclipsed Romantic folly if were not that the industrial revolution itself became again a new subject for the sublime.

Notably Piranesi the Italian artist (1720 - 1778) famous for his fictitious and atmospheric prisons, engineered structures and ruins provided an excellent reference and inspiration for artists in the 1800’s. The influential Scottish architect Robert Adam a friend of Piranesi shared a love of Roman antiquity and sublimity evidenced in his powerful architectural and structural compositions and the play of contrasting light and dark.

Scottish writer Alexander Gerard wrote in 1759 that, “When a large object is presented, the mind expands itself to the extent of that object, and is filled with one grand sensation, which totally possessing it, composes it into a solemn sedateness and strikes it with deep silent wonder and admiration: it finds such a difficulty in spreading itself to the dimensions of its object, as enlivens and invigorates its frame: and having overcome the opposition which this occasions, it sometimes imagines itself present in every part of the scene which it contemplates; and from the sense of this immensity, feels a noble pride, and entertains a lofty conception of its own capacity.”

Fast forward nearly a century later and Gerard could be describing people’s reaction to the breath taking completion of the Forth Rail Bridge when it opened in 1890 or the experience of seeing the launch of a great ship on the Clyde. The awe-inspiring complexity and scale of the Victorian capitalist-industrial system and its technologies borne of the enlightenment was to become a wonderfully rich source of speculation and concern for artists ensuring the pursuit of the overwhelming continued to evolve in response to the human experience of the time.

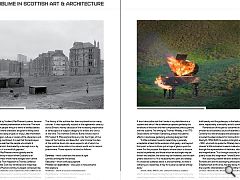

Without doubt Glasgow architect Alexander Greek Thomson (1817-1875) possibly one the most adept commercial architects of his day did not aim for his architecture to be beautiful but rather to move people. “The sublime moves, the beautiful charms.” philosopher Immanuel Kant stated (1724–1804). Sources of the sublime: infinity, vastness, magnificence, and obscurity were all qualities Thomson translated into architecture. Imagine therefore Thomson alive and able to witness the large-scale destruction of his grand tenements across Glasgow in the 1970’s, wrecked and burnt. Having survived two world wars Thomson’s architecture of awe was to be destroyed by the new order of modernism.

In his landmark essay ‘The Sublime is Now’ (1948), the American abstract expressionist painter Barnett Newman announced that ‘the impulse of modern art’ resides in the ‘desire to destroy beauty’. The problem with beauty, according to Newman, is that it prevents the artist from realising ‘man’s desire for the exalted’, in other words, for the sublime. Newman reacting against figurative arts preoccupation with beauty, the perfection of form, and the ‘reality of sensation’ advocated instead ideas of ‘the Absolute’. Similarly Russian artist Malevich sought to affirm the value of abstraction over realism, announcing in his suprematist manifesto that ‘the visual phenomena of the objective world are, in themselves, meaningless; the significant thing is feeling’.

A number of contemporary Scottish artists whose work regularly deals with ideas of fear, paranoia, obscurity and darkness are successfully reaching out to an international audience using ‘feeling’ as their muse. The seminal film piece 24 Hour Pyscho by the Glasgow artist Douglas Gordon took the great Hollywood film of the same name (Psycho) and slowed each frame down so that the film would take a full day and night to complete. The work is a visual hell fascinating to watch but incomprehensible in terms of narrative except through ones own recollections of the original Hitchcock film. Obscure, dark and part terrifying in the finest sublime tradition.

Similarly Martin Boyce’s unsettling Tramway show in 2002 again a seminal work in terms of recent Scottish visual art practice engaged the viewer in ideas of loss and absence when he presented an etiolated and everyday landscape where trees were florescent tubes, hedges where metal fences, light was cold and concrete. Boyce has developed an exquisite visual language and practice where he continues to amplify and explore in his words “the complete collapse of nature and architecture” and “finding beauty in the abject”.

Today contemporary Scottish and British artists have extended the vocabulary of the sublime by looking back to these earlier traditions and by engaging with aspects of modern society. They have located the sublime in not only traditional areas; the vastness of nature, industry, poverty, war, religion but also in new subjects modern science, film, finance you name it. The awe-inspiring complexity and scale of the capitalist-industrial system and in technology is a rich canvas. What of architecture then?

The challenge of not only making architecture that is functional, accessible, enjoyable but also transformational both aesthetically and conceptually is one that I have definitely burdened myself with, the sublime has for me been a central quality that I have sought to capture in my own work as an architect. I have not always understood that this was my ultimately goal but on reflection it was and continues to be.

Those close to me know I have a fixation for submarines since a student. I remember seeing an exhibition by an artist called Tom McKendrick in the Collins Gallery on the University of Strathclyde Campus in 1982 dedicated to the submarine form and its ambiguous aesthetic. As an architecture student I was instantly struck by the potential of the submarine to be a contemporary metaphor for a more appropriate Scottish architecture different to the Le Corbusier’s ship shape buildings that had crossed the Chanel from Europe. An architecture that was more self-effacing, climatically appropriate and awesome.

Recent Scottish architects whose work stands out for me as being sublime, self-effacing, and responsive climatically are Stephen Hoey’s team at Elder & Cannon, Mark Bell’s studio at NORD and Graeme Laughlan of RAW. Also Graeme Massie and Charlie Sutherland’s work can for me go beyond beautiful or as Burke wrote in 1757 “the pleasure comes in the suspension of the threat of deprivation” … something Scotland seems to excel in.

In this short text I have tried to link together historical preoccupation with the sublime in Scottish art a quality that I believe differentiates our national art from others. That is not to say the Scots have a monopoly on the subject it is just that this quality has been recognised as more distinct. This distinction is for me the one of the characteristics that if properly articulated and supported culturally could reinvigorate contemporary Scottish architecture as art. Across Scotland we have the unprecedented ‘Generation’ exhibitions that are showcasing the work of recent Scottish Artists. Architects should be part of the celebration.

|

|

Read next: Laurieston: Another Brick in the Wall

Read previous: Engineering survey 2014

Back to October 2014

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.