Biological Design: Brain Boxes

29 Oct 2014

Alan Dunlop has expanded upon insights gleaned from pioneering work at Hazelwood School, Glasgow, to explore the growing impact of neuroscience research on architecture. Discussing how human responses are shaped by the built environment from our body clocks through to our sense of touch Dunlop shows that neuroscience and architecture share common aims.

In the early nineties, I was commissioned by the Dementia Services Development Centre at Stirling University to investigate if and how the design of the physical environment, particularly in care homes, impacts on people with dementia. Much research from Australia and the United States of America existed, but there was a lack of precedent studies in the UK. The outcome of my research was a book, published in 1994, by DSDC: “Hard Architecture and Human Scale”, which includes examples of good practice and empirical studies, clearly indicating that architecture had something to say on the matter.As architects, we believe intrinsically that our work is important, and that the design of the physical environment impacts positively or negatively on the quality of life, people’s behaviour and even longevity. Usually this view falls on deaf ears. Politicians setting up procurement routes and commissioning programmes for the “delivery” of hospitals, health centres and schools are often the most sceptical. For them, quantity not quality, is the most important factor and in Private Finance Initiatives, Private Public Partnerships or “Hubs”, the bottom line is the main driver. Architects themselves however rarely have empirical studies to support their beliefs or are able to evidence that their buildings have a positive impact on people. Such studies take time and resources and architects usually finish their work and move on.

Today, it is estimated that 70% of people in nursing and care homes have cognitive impairment including Alzheimer’s disease. Although doctors are discovering more about the causes of dementia and clinical treatment is continually improving, there is yet no cure. The condition is progressive, and although precise definitions and diagnoses are difficult, all those affected will eventually become fully dependent and require long term care. Deterioration can occur quickly however and results in the complete loss of an individual’s personality and short term memory. In the latter stages people do not remember close family members and the brain’s ability deteriorates to the extent that cognitive and physical capacity is lost, and death occurs. The average life expectancy of someone diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease is five years. Studies from Australia and the USA indicate that good architecture and appropriate design of the physical environment for people with dementia slows the rate of decline.

Care homes that are well planned to encourage self reliance and independence and those designed with high levels of natural light and access to secure outdoor garden spaces, with visual cues, make it easier for people to find their way around without support.

Empirical studies on the importance of the physical environment have more recently been extended to cover many other aspects of the built environment and there are now multiple neuroscientific studies which evidence that an individual’s well being and health are directly impacted by the quality of their physical environment. This research provides insights into how the mind and the brain experience architectural settings but is sometimes hidden away in academic papers or obscured by scientific jargon; impenetrable to most architects, overlooked by politicians, and easy to ignore in an industry with differing priorities.

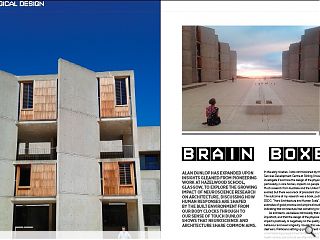

In 1992, Dr. Jonas Salk, the discoverer of the polio vaccine and a client of Louis Kahn, accepted the American Institute of Architects’ 25 Year Award for architectural excellence on behalf of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies. Through his relationship with Kahn, developed with the design for the Institute, Salk confirmed his belief in a “symbiotic” relationship between art, architecture and science and was convinced of the power of art and architecture to enrich the human experience. At the award ceremony in the Kennedy Centre in Washington DC, he said:

“By creating an environment that was in itself a work of art it was my hope that the Institute for Biological Studies would inspire the evocation of the art of science. Understanding that science cannot be divorced from art, the full meaning of each and both together will be better appreciated only through understanding their relationship, their relationship to each other and their relationship to man”

Ten years later, the San Diego chapter of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) formed the Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture (ANFA) at the Salk Institute. Under the direction of architect John Eberhard its mission was “to promote and advance knowledge that links neuroscience research to a growing understanding of human responses to the built environment.” Today ANFA is the only organisation in the world devoted to building intellectual bridges between neuroscience and architecture.

In May 2014, I was invited by Tom Albright, the current Director of the Salk Institute and by John Dale and Professor Claire Gallagher of the American Institute of Architects to present my ideas for designing for people with cognitive impairment at the Salk Institute Conference. For Albright, the conference was an opportunity to “further connections between the disciplines of architecture and neuroscience; to share existing knowledge; to investigate emerging research; to envision new research hypotheses and to forge interdisciplinary opportunities”. Albright and the AIA felt that the first ANFA conference in 2012 had missed opportunities related to design and architecture, with emphasis given over too much to neurology and the empirical impact of the environment on human perception and brain activity.

This second ANFA conference was intended then to promote the linkage between neuroscience and architecture. Two hundred and fifty architects, academics and researchers were particularly interested in Hazelwood School for children and young people who are blind and deaf. Hazelwood School in Glasgow is now recognised internationally as an exemplar project and used by Tom Albright and the AIA Committee on Architecture for Education (CAE) to prove to politicians and people commissioning across the USA the importance of design in creating potent spaces to support learning. Architect John Dale of the CAE remarked that, “there are lots of studies and claims out there but the literature is far from holistic and discussion very fragmented at best”. Hazelwood School and other projects I am now involved with are considered as making a direct contribution to this drive.

Although emphasis during this conference was on design and the importance of the physical environment to well- being, much of the focus centred around scientific papers and presentations on the “hippocampus, dorsal stream and spatial manifestations of the human psyche”.

Juhani Pallasmaa was the first keynote speaker for architecture. A Finnish architect and urban designer of international renown and author of over forty books on architecture, philosophy and the theory of the arts and architecture, he is though not a natural speaker and he laboured through a power point presentation. Pallasmaa informed the gathered scientists that;

“There are two levels of imagination: one that projects the formal or geometric and another that also simulates the actual sensory, emotive and mental encounter with the projected entity. The first category projects the material object in isolation, the second as a lived quality in the real world. True qualities of architecture are not formal or geometric, intellectual or even aesthetic properties; they are existential, poetic and emotional experiences and they arise from our embodied encounter with the work”.

Clear? The opportunity to be inspirational and to make direct connections between the two disciplines appeared limited from the outset.

The most accessible and informed presentation was given by Professor Peter Barrett of the University of Salford, who examined the impact of school design on learning rates and set out a clear connection between behaviour and the built environment. Barrett’s year long study of 34 classrooms: “Sensory Impacts on Learning”, explored differing learning environments and proved that design does matter.

It revealed that the academic performance of 750 primary school children was improved by up to 25% in schools with high levels of natural light, flexibility of space and good orientation with reduced noise pollution, ample storage facilities and good air quality. His findings stressed that placing an average pupil in a poor classroom environment can affect their learning progress.

Barrett’s study set up Hazelwood School perfectly and it was the first architecture project to be presented in full. The time allocated made it challenging to go into the 14 months of consultation and development undertaken with teachers, pupils, parents and clinicians that was fundamental to its design process but the subsequent animated discussion, questions and comments showed a clearly interested audience.

Although my career had moved away from designing for people with special needs, my work done on dementia in 1994 and my interest in designing environments to support people was to prove significant in winning the competition for Hazelwood School. Margaret Orr, Head of Services for Glasgow City Council and client for Hazelwood School stated: “Dunlop was commissioned as the architect for Hazelwood School and his design has been highly successful for children and young people with severe and complex needs and in developing their confidence and independence. The use of tactile materials to provide orientation references; the variation of wall and floor design to indicate different areas; the emphasis on maximising opportunities to allow natural light in to the building; the flexibility of internal learning spaces which allow for individual and group learning; the creation of an integrated but external garden, provides a range of activity and learning opportunities. Alan was one of the few who took an active interest in understanding the needs of the children and young people.”

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies, ANFA, and the AIA are to be congratulated for recognising the critical importance of architecture relative to neuroscience, but the conference evidenced the gaps in language between the two disciplines. Much more work is required to ensure that scientific developments are accessible to architects and that the contribution of architecture is made clear to researchers.

It is evident that although architect and scientist may share the same grand aims they do not speak the same language. Scientists prefer evidenced based concepts and the invitation to Pallasmaa was obviously intended to reveal the “immeasurable in architecture”, but failed in most part. The scientific method evident throughout the conference made scant connection to design and architecture but focussed on advancement in digital technology, biometrics and “smart” buildings.

Discussion after discussion showed logarithms indicating mood mapping, heart rate comparisons and neuro-sensory indicators, clearly reinforcing the interests of the majority of the audience. The presentation by Peter Barrett and my own moved the discussion to a more humanistic place and were well received.

It is clear that we have some way to go in developing a language that is understood and acceptable to both architect and neuroscientist, but the conference proved that with goodwill on both sides that there is opportunity for great benefit and I look forward to a return in 2016.

|

|

Read next: Maggie's Lanarkshire: Carefully Does It

Read previous: Fountainbridge: Seven Up

Back to October 2014

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.