Gray's School of Art: Gray's Matters

29 Oct 2014

Mark Chalmers speaks to the widow of Mike Shewan, architect of the threatened Gray’s School of Art in Aberdeen, to gain fresh insights into the legacy provided by the Miesian steel and glass landmark - in case it is needlessly lost to history.

Gray’s School of Art is an Aberdeen institution. There aren’t any other buildings like it in the city, nor elsewhere in Scotland. In fact, there are very few in Britain which compare to Gray’s.It was built during the 1960’s, when most buildings in Scotland were heavyweights. By contrast, Gray’s is a rare example of “High Modernism” built from steel and glass, which emphasises space and light over solidity and mass. But this architecture is technically demanding. Above all, it needs rigour – and that, it seems, was in the nature of Michael Shewan who designed Gray’s in the early 1960’s.

Mike Shewan was born in 1926, left school in 1943 and as a result, his training as an architect was interrupted by the war. Afterwards, his thesis project was a civic arts centre for Aberdeen’s Guestrow which won the architecture school’s Silver Medal for civic architecture. That same site, to the south of Broad Street, has been a problem in search of an opportunity ever since. St Nicholas House was demolished recently, and plans for the Broad Street’s redevelopment are being argued over as you read this article.

Shewan was awarded his diploma in 1954, but jobs for ambitious graduates were scarce in the city – again, how little changes! Along with several friends, he sailed for Canada where he joined Adamsons, the leading practice in Toronto. As a student he was interested in the work of Mies van der Rohe, and later considered himself to be a follower of the Miesian approach: now he had the opportunity to study the master’s work at close quarters.

In Canada, Mike Shewan worked on a series of large projects, and in his time off he made at least two trips to Chicago. His wife-to-be Norma joined him on the second trip during the Fall of 1958, down through Chicago and Detroit to St Louis, then back up through New York and the Great Lakes. The principles Shewan absorbed in Chicago came directly from the source, because High Modernism speaks American English with a German inflection.

The tower blocks at 860-880 Lake Shore Drive were an early example of Mies’s skin and bones architecture, and had been completed for several years, but Crown Hall at the Illinois Institute of Technology was boxfresh, and down in New York the Seagram Building was newly-finished. The impact of these buildings on a young architect shouldn’t be underestimated.

Key to understanding the genesis of Gray’s is that Miesian architecture relies on a set of principles, not a style. Over time we’ve had trouble distinguishing the shades of grey between principles, influence, homage and pastiche but as Mies said of his imitators, “Our buildings need not look alike, after all, there are 10,000 species of seashell. They don’t look alike, but they have the same principle.” That was an important lesson.

After five years working in Canada, including a year immersed in structural engineering, Mike Shewan came back to Aberdeen in 1959 to work with David Ross at Allan, Ross & Allan whose stock-in-trade was designing the city’s schools. Shewan later moved to the practice of Tom Scott Sutherland, the one-legged architect and entrepreneur. Scott Sutherland had gifted his house and estate at Garthdee to Robert Gordon’s College a few years before; after his death, Shewan took over his practice.

Even before the Oil Boom, Aberdeen was a solidly affluent place, many of whose architects worked in old-established practices which made their reputations building the Granite Mile of Union Street. Aberdeen bred characters such as David Ross, Leo Durnin and especially Tom Scott Sutherland: they all had some peculiarity, but those I’ve met and others whose stories I’ve heard were not at all provincial in attitude.

The architecture school at Robert Gordon’s College, from which Mike Shewan graduated, was later named Scott Sutherland after its benefactor. It was first to move from Schoolhill to Garthdee, in 1956, and by the early 1960’s Gray’s School of Art had also outgrown its old home.

A site for the new art school was chosen on a bluff west of Garthdee House, a mansion built by William Burn even before Victoria put the Royal into Deeside. It sits on the lower reaches of the Dee in mature parkland which falls towards the river, and around it is a rolling lawn where monkey puzzle trees dip and dance in the breeze.

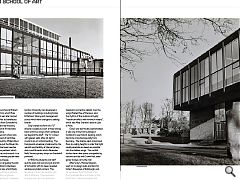

The new Gray’s is arguably the last building of pre-Oil Boom Aberdeen. It consists of a glass box which floats above the lawn, providing an elegant counterpoint with the cut-granite Baronial of Garthdee House. However, over the past 20 years, the Robert Gordon University has developed a number of buildings including Foster & Partners’ library and management school which have changed its setting forever.

Gray’s takes the form of a “U” around a sculpture court: a three-storey block with two wings which cantilever out beyond the bluff. The “U” is lined with glazed walls: after all, light is crucial in an art school building. The transparent envelope is balanced by the warmth and tactility of internal joinery, doors and fitments which Alexander Halls’ famous joinery shops on Granitehill provided.

In 1968, the students and staff quit the dust and soot and grit and lint of Schoolhill, with its deep-revealed windows and dark corners. The language of their new building was utterly different. The expression of space and light is its grammar; everything that follows is idiom. The steelwork connection details, how the wings floated free of the lawn, and the rhythm of the mullions all typify “maximum effect with minimum means”, which was Mike Shewan’s take on Less is More.

Gray’s was technically sophisticated: it was one of the first buildings in Scotland to use Holorib decking, which had to be imported specially from Germany. The shallow deck maximised floor-to-ceiling heights in order that light could penetrate as deeply as possible into the shallow wings. The northlit studios have clear spans unimpeded by columns and as with Crown Hall, steel girder trusses carry the roof.

After Gray’s, Michael Shewan went on to design pubs and bars for Usher’s Breweries of Edinburgh, and he succeeded Scott Sutherland as the Clydesdale Bank’s architect in the North East. Later he designed the Tube Ice Plant at Peterhead harbour which produced ice for the deep sea fishing fleet. The latter highlights Shewan’s interest in process, and the analytical side of his mind which liked to understand how things work.

Shewan’s unbuilt work includes a scheme for Aberdeen’s first luxury hotel, a Hilton which would have been built in the late 1970’s on the Hill of Rubislaw, using a site now occupied by oil companies Chevron and Marathon. Like Broad Street, Rubislaw has been a prime site for decades, and Mike Shewan’s elegant cuboid is arguably more fitting than the sprawl of offices which has emerged over the past 30 years.

During the early 1980’s, Michael Shewan worked in Barbados for a year, to develop his ideas for underfloor cooling using pipes cast into the floor slab. When he returned to Scotland, he started a company, Civic Restoration & Development, with Raymond Harrow. They worked on many conservation projects over the next few years, including schemes in Old Aberdeen which won several awards. Later, he formed a partnership with John Mackie, then finally moved to Forres where he retired from practice.

Michael Shewan’s career followed a similar arc to that of his contemporaries, such as Robert Matthew. As a young architect he was in the vanguard of Modernism, and picked up important civic commissions which made his reputation. He tackled technical architecture alongside set-pieces, and later created a vehicle to carry out conservation work. Over the course of a lifetime, Mike Shewan became a complete architect whose work touched each sphere within the profession.

As for the future of Shewan’s most accomplished building, a report commissioned by the Robert Gordon University (RGU) in 2008 stated that Gray’s is no longer fit for purpose. It’s intended that the art students will move into a new building in the next couple of years, and Stage 7 of the Garthdee Masterplan from 2009 proposes demolition of Gray’s: although when I spoke to RGU recently, I was told they had no definite plans for the building once it’s been vacated.

Stuart MacDonald, former director of The Lighthouse who went on to become Head of Gray’s School of Art, noted in 2007 that Gray’s “straddled massive changes in education and art and design, and has taken each initiative in its stride. Its simplicity is its flexibility, and in its 40 years it has demonstrated a seemingly endless capacity to absorb more students, innovative developments and new technologies.”

Gray’s was included in the DoCoMoMo Register in 1993, as one of the sixty key Modern buildings in Scotland, and it has already been assessed for listing by Historic Scotland. They noted that Miesian buildings are rare in the UK, particularly outwith London, but Gray’s is “an outstanding example of post-War Modernist architecture.”

You have to look hard to find anything comparable. Basil Spence’s practice built a couple of glass and steel buildings for universities – the Roger Land Building at Edinburgh, and the Physics Building at Liverpool – but neither demonstrates the same conceptual rigour, or determination to follow that through into the detailing. In fact, you need to travel south to Darlington, to the Cummins Engine Factory designed by Kevin Roche in 1966, to see the same purity of intent and execution.

Like Gray’s, Cummins is rigorously ordered and used technology which for its time was cutting-edge: in its case, neoprene gaskets were used to glaze the windows into their frames. It’s no coincidence that these two buildings are exactly contemporary, because the mid-1960’s was the high point of High Modernism in Britain. So, what changed?

Architectural history works in cycles. During the Sixties, Mies van der Rohe came close to achieving his goal of a pure architecture of space and light. However, that fell out of fashion in the 1970’s and was rubbished in the 1980’s for its poor energy efficiency.

Its failure is partly down to the technology available when Mies conceived his Chicago buildings. We can do better now: plain float glass can be replaced with clear-coated solar control glazing and combined with active window blinds. Single-ply membranes can be substituted for mineral felt roofing, and Rockwool performs better than woodwool slabs. Half a century after it was conceived, we finally have the technology required to make High Modernism work as its designers intended.

Mike Shewan introduced North American architecture to Aberdeen almost half a century ago, yet Gray’s untrammelled, light-filled spaces seem timeless. By contrast, the Modernism we’ve fought to preserve over the past 20 years consists of earth-bound churches built from sewer brick, beton brut and stucco.

That needs to change if buildings like Gray’s are to survive.

|

|

Read next: Fountainbridge: Seven Up

Read previous: Scotland's Future: Independence Nay

Back to October 2014

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.