Fountainbridge: Seven Up

29 Oct 2014

From Malmo to Freiburg urbanists have often looked to Europe for contemporary design exemplars, but may soon be able to turn their eyes closer to home if Edinburgh’s ambitions for Fountainbridge play out as planned. Here Ewan Anderson of 7N Architects outlines the principles which underpin a post credit crunch master plan that seeks to prioritise long term investment over short term profit.

The Fountainbridge project represents an opportunity to deliver a long term civic investment in placemaking in Edinburgh, marking a significant shift in direction away from the way in which key sites have been developed in the city in recent decades.Major developments such as Caltongate, Haymarket and Craighouse Campus have the common thread of a disposal of a publicly owned property asset, generally to the highest bidder, followed by lengthy and fractious planning processes which has pitched local communities against developers. These have ended up being hugely expensive and time consuming processes for all concerned when the money and energy devoted to battle could have been spent on making the city a better place.

The team on the Fountainbridge project has set out to do things a little differently, with the City of Edinburgh committed to developing it as a long term civic project based on a placemaking strategy which has evolved from an extensive dialogue with the local community.

Wellies, beer and bankers

The Fountainbridge site forms part of the swathe of formerly industrialised land which arose around the canal and railway infrastructure constructed to the west of the city centre in the nineteenth century. It was the home of the North British Rubber Company (manufacturing Hunter wellies amongst many other things) until the construction of the Scottish and Newcastle Brewery in the 1970’s. These industries brought many jobs, which are now long gone, but the legacy of the infrastructure is the area’s relative disconnection from the surrounding neighbourhoods, creating a perceived void in this part of the city. It is a pivotal site in terms of its potential for knitting this western edge of the city centre together.

This was recognised in the range of masterplans and planning briefs which have been prepared for the site in the past decade, since Scottish and Newcastle ceased their brewing operations, but none of these proposals have been delivered. HBOS, who bought the site from S&N, intended to build their global HQ on it before the credit crunch brought that initiative to an abrupt end in 2008 with their takeover by Lloyds Banking Group. It is perhaps a sign of how much things have changed in recent years that this now seems like a very distant era.

The City of Edinburgh Council acquired the site at Fountainbridge from Lloyds in 2012 for the development of a new Boroughmuir High School. The 3.3 hectares of land to the east of Viewforth was not required for the school and a decision was taken to retain it for development. The EDI Group Ltd, the City of Edinburgh’s arm’s length development company, who are responsible for taking the development forward, commissioned a masterplanning team, led by 7N Architects, to develop a masterplan for the site.

Integrated placemaking

The aim, from the outset, was to develop a placemaking strategy that was integrated with a development framework that would deliver it over the long term and optimise the civic and commercial opportunity. The approach was based on the simple premise that good places draw people to them, stimulating demand which, in turn, drives value in its widest sense.

One of the things which sets the Fountainbridge project apart from many major projects in Scotland is the alignment between design ambition, the delivery model, and civic investment. Such synergy is more commonly found in Northern European countries where the city authorities play a more significant role in leading civic projects. They often act as landowner, developer and masterplanner, determining the quality of the place by putting in the infrastructure and public realm before selling or leasing the plots to private development partners. The upfront investment is recouped from enhanced land values and increased tax revenues resulting from the transformational change, plus the wider economic benefits to the city.

Although the likes of Malmo B01 and the Eastern Docklands of Amsterdam are frequently presented as design exemplars it is arguably the processes which delivered places of such quality where the most important city making lessons lie. Sadly, Edinburgh’s Waterfront stands as a monument to what happens when the delivery process is not aligned with the civic ambition.

But there is now an opportunity to fix this, and the other critical dimension of the development equation which determines the quality of the future place is time. A long term approach to property investment encourages a higher level of quality so it will endure and consequently grow in value. With the short term model, that has driven so much residential development in the UK, there is perversely a disincentive to invest in quality as the cost effectively reduces the profit and the investor has no interest in the future value once it is sold.

Although the economics of this may be a rather dry subject (I am grateful to Matthew Benson of Rettie and Co for explaining it all so tangibly) it is a hugely significant to the future of city making in this country. With the short term approach hitting the buffers in the credit crunch one of the few positives arising from the recession is that the move towards longer term investment in property should facilitate a development culture that creates better places.

But this is not new. Edinburgh’s New Town was funded in this way with the feu system and Fountainbridge will be an opportunity to get back to such long term thinking as a basis for enduring city making.

Community engagement

Positive engagement with the community has been a key factor in the development of the masterplan and the project ethos. The engagement took place at an early stage on the project, as an open conversation with a relatively blank sheet of paper, rather than the retrospective form of consultation on an effectively completed design which is too often evident in planning applications. The City of Edinburgh and the EDI Group should be applauded for having the confidence to open up the dialogue to this degree and thanks should also go to the Local Councillors for giving it such strong, cross party, support.

A series of workshops were held with the community and key stakeholders in the latter half of 2013 led by 7N Architects and Riccardo Marini, Edinburgh’s City Design Leader. The consultation established a set of principles at the outset to determine the aspirations and requirements for the masterplan. These were aligned with a set of reference images, selected by the participants, to articulate “what kind of place it should be.” These exercises established a common vision for Fountainbridge which formed the basis of the strategic approach. This was then developed, over the course of the three workshops, into a series of masterplan options which were iteratively refined through intensive debate into what became the preferred masterplan.

The main outcome of this process was consensus on the masterplan, which is now the basis of the current planning application, but the real long term value of it will perhaps be the way it which it energised all of the participants around a common ambition and vision for the site. A local community group, the Fountainbridge Canal Initiative (FCI) who have been actively involved in the site for many years, were key contributors to the workshops and continue to be heavily involved in the project as members of the Sounding Board and the vanguard temporary uses such as the Grove Community Garden.

The masterplan

The engagement workshops set a very clear agenda for the masterplan; to deliver a vibrant, liveable, neighbourhood that will re-invigorate the canalside and surrounding area with a range of mixed uses and housing types.

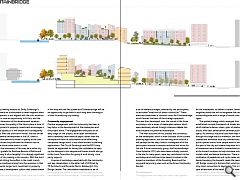

The spatial strategy which emerged from this established a simple framework of streets and spaces which defined a dense, urban, grain of relatively low rise blocks with clear demarcation between public and private space. As previous industrial uses have kept routes through this large site to a minimum, the framework creates and reinforces local city connections to shape public spaces around how people want to move through this part of the city and where they want to be. Patterns of movement were studied to concentrate mixed uses at the busiest locations to help stimulate activities and sustain retail and leisure businesses. There is a natural confluence of pedestrian and cycle routes where the desire line along the towpath meets the Leamington Lift Bridge crossing to Gilmore Park which provides the only direct connection to Haymarket. This is the hot spot where most of the retail, cafes and hotel uses are concentrated plus a new, canalside, cultural facility that will be a hub for creative industries. Secondary routes will allow people to filter through the site to establish a hierarchy of routes and movement which will create quieter spaces, appropriate for family housing, within the heart of the neighbourhood.

The canalside is the key space where people will want to be. A south facing, waterside, promenade with a backdrop of cafes, shops and restaurants and a new, stepped, edge to the canal for casual seating and launching small watercraft. The space is of a similar scale and orientation to the Grassmarket which was used as an Edinburgh benchmark of a lively place that successfully accommodated a wide range of activities. Water features and water gardens run deep into the site from the canalside to signal the presence of the canal from Dundee Street, to the north, which is at a much lower level.

The public realm will be pedestrian and cycle dominated with limited vehicle access and the majority of parking tucked under a deck that is flush with the towpath. The same deck also conceals a food store, a relocated substation and the energy centre which will power the new neighbourhood’s district heating system, to avoid these larger elements impinging on the close knit grain of the streets and spaces.

These moves are also important in creating a pleasant and safe environment for family living in the city centre. A key theme during the engagement was that the new place should be embedded in the social fabric of the area and should not become an isolated dormitory of two bedroom flats. This pointed to a range of housing types and tenures, with a particular focus on family housing to meet local demand and to help to root the new neighbourhood into the local community. There is therefore an emphasis on many of the 340 new homes being dense, urban, typologies with additional outdoor space provided by an animated roofscape of terraces and roof gardens which will bring greenery and activity to the skyline.

These are important elements of the proposals as a key test of the success of the development, over time, will be the degree to which the new neighbourhood is colonised and cherished by those who will live there.

Growing The Place

Advance initiatives are already underway to bring temporary uses on to the site to bring it to life and cultivate positive perceptions of the place in advance of development .

The first two phases, the FCI’s Grove 2 mobile community gardens and a temporary greening initiative by the Edinburgh and Lothians Greenspace Trust have already been implemented along with a circus and pop up hotel during the Edinburgh Festival. The temporary greening, through a series of tree lined pathways, has established the footprint of the public realm on the site, opening up the site to pedestrians and defining the plots. The colony of temporary uses will gradually be replaced with the permanent uses as construction begins and each plot is developed.

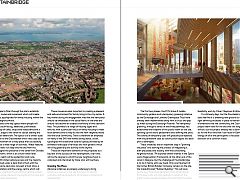

These initiatives are an important step in “growing the place” and starting the process of integrating it, both physically and socially, with the surrounding neighbourhoods. 7N explored similar themes in the Speirs Locks Regeneration Framework, at the other end of the canal in Glasgow, but the challenge at Fountainbridge is to do it mainly with new build. Only one fragment of the former British Rubber Company remains on the site, the Grade B Listed “Rubber Building”. This will soon be the new, Page\Park designed, home of Edinburgh Printmakers who are now gleefully in receipt of the grant funding needed to take it forward following initial feasibility work by Oliver Chapman Architects.

It is still early days, but the Fountainbridge project does feel like it is breaking new ground as it has the right delivery processes in place to realise the high level of ambitions that the community, the Council and the project team have for the site over the long term. Time will tell, but the project already has a distinct advantage as, for the first time that I can recall in Edinburgh, the energy of all of the participants is focused in the same direction on a common vision.

|

|

Read next: Biological Design: Brain Boxes

Read previous: Gray's School of Art: Gray's Matters

Back to October 2014

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.