Dundee - City Break

16 Jul 2014

Dundee is a city in flux as its waterfront ambitions make the leap from drawing board to reality. These changes are beginning to have a profound impact on the city’s relationship with the river, a brutal process which Mark Chalmers describes as the ‘unmaking of modernism’. Here Chalmers sifts through the rubble and takes stock of the transition.

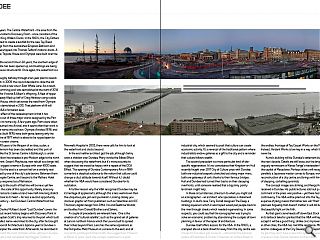

A line of truckmixers sit, with drums spinning impatiently, while a giant crane eases out into the rush-hour Marketgait. Wheel after wheel creeps forward until ten axles have emerged, then the big green beast heads off in a convoy of flashing lights. Behind it traffic starts to flow again, past a backdrop of excavators and rubble.For the past couple of years, Dundee’s Central Waterfront has been gradually remade. Until recently, it was a confluence of ramps and overpasses from east, south, west and north. Today new roads snake through a landscape of earth-movers and altered priorities. The re-development is hung on the V&A at Dundee, an outstation of the Victoria & Albert Museum. Kengo Kuma won the design competition in 2010 and now that funding seems secure, the enabling works have begun.

The new waterfront will combine culture, infrastructure, traffic management and the provision of hundreds more hotel beds and restaurant covers. The Tay Road Bridge landfall has been reconfigured. The railway station concourse and ticket hall will be rebuilt, with an “air rights” hotel over it. The ultimate aim is to create a new grid of streets around a landscaped square.

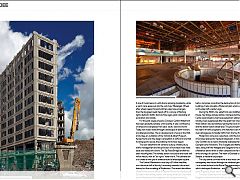

The Central Waterfront is not only a £1 billion headline, nor a decisive shift of the city’s economy towards culture and leisure, but the unmaking of Modernism. The recent demolition of the former council offices at Tayside House; the rebuilding of Dundee’s main railway station; the razing of the Earl Grey Hotel, and the flattening of its neighbour the Olympia swimming baths, comprises more than the destruction of individual buildings. It also disrupts a Modernist plan which was imposed on Dundee half a century ago.

During the 1960’s, the waterfront was stratified. Tayside House, Tay Bridge railway station, Olympia and the Nethergate Centre were linked by high level pedestrian walkways. The railways were suppressed after the great train shed of Dundee West Station was demolished, leaving the Dock Street tunnel and the station below street level. The ground plane became the realm of traffic engineers, who hatched a set of ramps and dual carriageways to handle traffic from the Tay Road Bridge.

Modernism came as a rude shock. Until the Sixties, the core of Dundee retained its medieval street plan. In fact, it was the only Scottish city to resist wholesale redevelopment by the Georgians and Victorians. The Overgate and Nethergate to the west, along with the Wellgate and Seagate to the east, formed a flattened saltire which is often compared to the outstretched arms and legs of a person. The heart of Dundee is still the Auld Steeple, a medieval skyscraper.

The city centre survived more or less intact until a dual carriageway was forced through the medieval gaits and wynds – in a similar fashion to the Bruce Plan motorways in Glasgow which destroyed Anderston – and this disrupted Dundee’s tight grain. Arguably, worse was to come.

The city’s docks lay to the south of the Nethergate and Seagate, on land reclaimed from the Tay over the course of hundreds of years. The Central Waterfront – the area from the modern Apex Hotel to Discovery Point – once consisted of the Earl Grey and King William Docks. In the 1960’s, the City Fathers had them infilled to create a landfall for the new Tay Road Bridge. Siftings from the demolished Empress Ballroom and Royal Arch were tipped into Thomas Telford’s historic docks. A few years later, Tayside House and Olympia were built over the remains.

Now, for the second time in 50 years, the southern edge of Dundee’s centre has been opened up, and buildings are being crushed for use as structural fill. Once again, the waterfront is a tabula rasa.

We are roughly halfway through a ten year plan to rework the waterfront. In 2009, the council decided to close the old Olympia and build a new one in East Whale Lane. As a result, the former swimming pool was demolished at the start of 2014 to make way for Victoria & Albert’s offspring. A fleet of tipper lorries has already filled up half of Craig Harbour using rubble from Tayside House, which sat across the road from Olympia and had been demolished in 2013. That platform of fill will become the V&A’s formation level.

One side-effect of the redevelopment is that it has destroyed two out of three major works designed by the Parr Partnership in its home city. A few years ago, Parrs were taken over and subsumed into Archial, and it seems that their work is following their name into oblivion. Olympia (finished 1974) and Tayside House (built 1976) have both gone, leaving only the Wellgate Centre of 1977 which is about to be ripped apart to create a multi-screen cinema.

Perhaps 40 years is the lifespan of an idea, a plan, a building. Modernism has been discredited and this part of Dundee, just like the St James Centre in Edinburgh, is under attack. Demolition has revealed a pre-Modern edge to the north of the waterfront. Green’s Playhouse, now rebuilt as a bingo hall, was once the biggest cinema in Europe with over 4000 seats. The Caird Hall to the east is a concert hall on a similarly vast scale, endowed by one of the city’s jute barons. Between them lies the Nethergate Centre, and beyond is the Mathers Hotel which recently reopened as a Malmaison.

Everything to the south of that line will be new; yet few acknowledge the scale of this opportunity. Rarely does any city get the chance to create a brand new half-mile long stretch of riverfront close to its heart – far less a second opportunity within half a century – but Dundee’s Central Waterfront has quite a history.

The late Charles McKean’s book “Lost Dundee” covers the distant past, but recent history begins with Discovery Point in 1989, when Captain Scott’s ship returned to the port which built her. Enric Miralles’ name was linked to the city, after he brought Frankfurt School of Architecture’s diploma year to Dundee in 1999 to masterplan the waterfront. Afterwards, he described it as one of the most the most dramatic urban settings in Europe. Once Frank Gehry had completed the Maggies Centre at Ninewells Hospital in 2003, there were calls for him to look at the waterfront and docks beyond.

In the end neither architect got the job, although Gehry casts a shadow over Dundee. Many invoke the Bilbao Effect when discussing the waterfront, but it’s more accurate to suggest that we would be happy with a repeat of the DCA Effect. The opening of Dundee Contemporary Arts in 1999 converted a skeptical audience to the notion that culture could change a city’s attitude towards itself. Without it, I doubt whether the V&A would have considered Dundee for its outstation.

A further reason why the V&A recognised Dundee may be its heritage of applied arts, although this is less well known than the ubiquitous jute, jam and journalism. Looking closely you discover graphic art from publishers such as Valentines and DC Thomson; digital design from DMA, Viz and Realtime Worlds; and textiles from Donald Brothers and Sekers.

A couple of precedents are relevant here. One is the creation of a “cultural satellite”, such as the grand set of galleries at Lens in northern France which the Louvre built to spread their riches beyond Paris. Lens has the same aspirations as the Pompidou-Metz Museum in Lorraine to the east, and of course the prototype for them both, the Guggenheim Museum at Bilbao in Spain. Each was a major investment in a post-industrial city, which seemed to posit that culture can create economic activity. It’s a reversal of the traditional pattern where industrialists endow galleries as a gift to the city and a reminder that culture follows wealth.

The second precedent is a more particular kind of site-specific regeneration. It’s no coincidence that Kingston-on-Hull recently fought over 2017 City of Culture prize with Dundee: both are industrial seaports stretched out along major rivers, both are gateways of sorts thanks to their famous bridges. Hull and Dundee had turned their backs on their decaying riverfronts, until someone realised that a big shiny pointy landmark might help.

In these circumstances, cities turn to what you might call an iconographer – an architect who specialises in statement buildings. In Hull’s case, Terry Farrell designed The Deep, a striking aquarium which it was hoped would pull people back to the river through streets which needed regenerating. In some respects, you could say that the iconographer was trying to solve an economic problem by abandoning the cudgels of town planning in favour of the rapier of architecture.

Dundee itself offers lessons for the V&A. In the 1990’s, a cramped site on a back street far away from the city centre was chosen for Dundee’s jute museum – rather than the Baronial palace of Robertson & Orchar’s Calender on Victoria Road, or the endless frontage of Tay Carpet Works on the Marketgait. Instead, Verdant Works is low key in a way which the V&A will never be.

Kuma’s building will be Dundee’s statement building for the next decade. Details are still loose, but the language is vaguely reminiscent of Kenzo Tange’s masterplan for Skopje, the capital of Macedonia. Perhaps others will recognise the parallels: a Japanese master comes to Europe, working on the reconstruction of a city centre, and brings with him a language of stepping, corbelling pyramids.

The concept images are striking, and Kengo Kuma was well received in Dundee. His public lectures sold out quickly, and comment in the press was positive – yet there has been some controversy. The V&A will be piled out into the Tay, although the expense of piling means that rather less will “float” than initially planned. Arguably that doesn’t matter; it will still benefit from the beautiful light on the firth.

As that giant crane heads off down East Dock Street, those in its tailback take for granted that the V&A will happen, and accept it will be a good thing. Unlike civic improvement plans in other cities, the V&A has met little resistance. Mike Galloway and his colleagues at the City Development Department must be glad they don’t have a new tram system, a George Square, or even a Union Terrace Gardens on their hands.

Read next: Recruitment - Just the job

Read previous: Procurement

Back to July 2014

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.