Architectural Photography

15 Apr 2014

Always there but never seen architectural photographers are the ghosts of the profession, unnoticed and undervalued. To redress the balance urban realm invited four leading proponents of the craft to step out from behind the lens to give their perspective on what makes the perfect image.

Andrew Lee is a photographer more painfully aware of these misconceptions than most, telling urban Realm: “I’m surprised that someone will spend three or four years on a project and take away nothing from it. Only the client and a few end users will know about it and in the case of private housing it might just be one person. It would be like a film director showing their new release to a friend in the living room, why would you not want to reach a wider audience with your achievements as a stepping stone to your next project?”

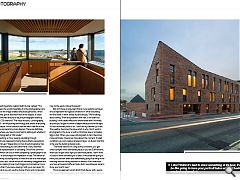

Comprehensive coverage in a journal might feature (at most) 12 photographs, on a website maybe six or eight and in a magazine article just one or two and it is through this vanishingly small window that practices must showcase their wares to the wider world. Lee observed: “In a magazine or journal people might read the text but they’ll certainly look at the picture. Architecture doesn’t translate into words, especially the words that most architects use which tend to be aimed at other architects. There is something less mediated about the graphic image, it allows the viewer to make up their own mind.”

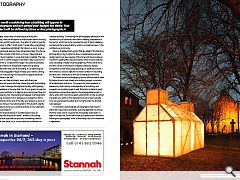

Adding his voice to the mix photographer Tom Manley added: “Having worked in practice for a decade, changing career to pursue a passion in photography has been an interesting process. The challenge is to bring together elements of space, light and time – to break a building down to its primary qualities. A practices work, and reputation is experienced through these images as much as by the people who live and work in its buildings. Digital media and blogs bring this work to a wider audience, and hence the importance of images that offer fresh and striking perspectives has never been greater.”

Fellow photographer Neale Smith, who liaises regularly with Lee and Manley, advocates collaboration with the architect at the earliest stage to achieve the best results, ideally including a site meeting to pick up on any details which need to be highlighted, allowing him to concentrate on the technical aspects. “At this point it’s good to feed my own experience and technical knowledge to them and make suggestions based on what they want and what I know is technically possible,” advises Smith. “Technicalities aside, the dressing of an interior is also extremely important, more often than not you spend as much time moving furniture and other objects around as you do composing and lighting the scene.”

Vehicles may be the bane of urbanists but they are a particular irritant to architectural photographers who must somehow find a way to prevent the omnipresent metal lumps from ruining their shots. “I have found myself offering to pay irate motorists to move obstructing vehicles’ remarked Manley, who must also contend with street furniture, bin stores and neglected landscaping. But where do you draw the line between an honest reflection of reality and a dishonest enhancement? “I’ll use digital manipulation to overcome limitations of the camera such as exposure, especially when you’ve got contrast between the indoors and outdoors. I’ll also use it to remove things that shouldn’t be there; so if I’m told something will be snagged then I feel justified in airbrushing that out. Similarly if something is scuffed through wear and tear, I’ll airbrush that out too - but I’m careful to avoid anything which affects the design and execution.”

Does this mean that the camera lies? Lee answered: “The camera always lies! A camera taking a very raw photograph, a very naive photograph, is lying. It’s making the building look worse than it is. I’m ‘lying’ if you want to put it that way, by making it look better than if you just turned up - but there’s a greater truth in my photograph in that I’m describing the intent and the execution. By retouching a fire extinguisher or some signage I’m removing distractions to allow the viewer to appreciate the design. I’ll never make a building look worse than it is, I’ll always make it look better. At the end of the day we’re interested in seeing things at their best, it would be like photographing a car on a smartphone for an advert. It is all about selling, it’s selling ideas. No-one is selling the building apart from a developer but architects are selling their vision, their principles and their ideas about what makes a good building. “

Picking up on this theme when asked whether CGI’s are now approaching photo-realism Keith Hunter replied: “The camera views the world impartially, it is the photographer who dictates how the image created should be perceived, which can, if desired, give a distorted view of the subject. It could nearly be switched around to say are photographs starting to look like CGI creations? The visual industry – photography, film and TV - are all pushing technology that shows everything brighter, sharper, more colourful than we see in real life so the boundaries are becoming more blurred. There are definitely instances where you have to look hard to distinguish whether it is a ‘real’ photograph or CGI render.”

Commenting on how viewing a building through photography (as opposed to being there) affects perceptions Hunter continued: “Depending on how the photographer has captured the building you can either have a very distorted or accurate representation of a building. One of the common problems which can occur when comparing a photograph to an actual visit to a building is the impression of size. The nature of photographing a building tends to need the use of a wide angle lens to record it as a whole which will inevitably exaggerate the perspective, making it look much bigger and sometimes more impressive than if you were viewing it with your own eyes. On the other hand you can use the choice of lens and composition to concentrate on a certain design aspect of a building which may not be easily noticed if present.”

But isn’t there an argument that a more realistic portrayal should represent the typical conditions in which a building will find itself, in other words dull and drizzly: “We’re talking about selling. There are problems with rain, it will stain the building. It will create reflections where there aren’t normally any and you’ve got no sense of depth because of the flat light. It’s also technically hard to do, I can’t set my camera up in rain. The weather becomes the issue which is why I don’t want to photograph in the snow or with a Christmas tree or an Easter Egg in shot. When you a see a photograph in rain it becomes more particular, it becomes more about the moment. In ideal conditions you can create a timeless image - an illusion that this is the way the building always looks.

“There are reasons for using sunny conditions, you get direct sunlight which delineates place so you see 3 dimensions, when you’ve got direct light you see those planes. I don’t think it’s bad to show something at its best; it would be like going to have your portrait taken and deliberately going first thing in the morning without having washed or shaved. As an individual you have a thousand different looks but it would be perverse to show your worst view.”

This is an approach which Smith finds favour with, saying: “My view is that photography is an intrinsic part of architecture, it’s the longest valued way of recording a building two dimensionally, with the exception of more recent trends moving towards video and 3D renderings - the latter of which is rare for a photographer to offer.“ Smith adds: “I quite often use lighting to enhance, separate and highlight furniture in a room, to give the two dimensional space a three dimensional feel. One frame can quite often consist of 50 shots or more, it takes skill and time to put them together in a way that looks credible. The idea of blasting out 50 awful images in less than a day is just not on the radar. I think it is important to keep it as subtle as possible though, over enhance it and people might end up being disappointed when they visit the building. It’s a balancing act between producing great images to keep your clients coming back and not overcooking it to the point the space becomes unrecognisable in real life.”

There are very few architects, even with their own buildings, who will spend a full day interacting with the building and seeing how it changes throughout the day whilst getting objective feedback in the way that I do. If your goal is to use this project for your portfolio or to lead to your next project then it’s worth considering how the building will appear in photographs. One example would be not to spread your budget too thinly over a building as at the end of the day your project is going to be defined by three or four photographs. Why build 15 slightly different features when you could have three or four elements with real visual impact?”

“Medium-sized practices in Scotland spend less on photography than they do on toner”, laments Lee, noting that any fool with a phone can produce something called a ‘photograph’ but fewer of us would have the confidence to create a building. Contrasting the photography profession with architecture Lee observes that there is healthy competition in the sector, which has so far avoided the sort of back-stabbing and behind the scenes bitching which is sometimes seen in the architecture community.

Having straddled both worlds Manley added: “Architecture photography is by its nature a slow, considered process and design teams can be unaware of the time and the procedures involved in getting the required results, which include making sure a building is ready for photographing. Photos tell a story and this can be overlooked in imagery fuelled by design competitions, that often judge buildings on aesthetics alone. I think there’s a case to capture the wider context of a building, and the user’s interactions with surrounding environment.

“Architecture and photography should influence each other. By taking time to look closely at a building project, a process of familiarisation will occur. Comments by local residents or passers-by often aid my understanding of a building, and suggest how to photograph it well. Attention to detail in post-production is where the majority of a photographers work is done, often with more time spent editing than on site shooting! Generally you want to limit retouching so as to best recreate how you perceived the place and moment when the shutter was released.”

In contrast to a photograph, photography itself doesn’t stand still, requiring a constantly evolving approach to ensure that the wider world - beyond the immediate client team, is kept in the picture. So the next time you spend a few moments looking at a photograph, think of the many hours of investment it represents.

|

|

Read next: Cowgate

Read previous: Union Street

Back to April 2014

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.