Hull

15 Apr 2014

It edged out Dundee and embarrassed Aberdeen to claim the UK Capital of Culture crown for 2017, but what was it about this former industrial centre which attracted the judges? Here John Lord of yellow book travels south and discovers a city whose fortunes may finally be about to turn.

The decision to make Hull the UK City of Culture 2017 was a surprise. The smart money was on Dundee, which mounted a confident campaign built around the regeneration of the Tay waterfront and Kengo Kuma’s V&A. Things are happening in Dundee, and maybe that was the problem. The judges’ feedback questioned whether City of Culture status would make as much difference in the city of Discovery as in struggling Hull.These decisions are almost always impenetrable, especially so in this case because the UK Culture Secretary, Maria Millar – who appears to have no interest in the arts at all – had the final say. But Hull’s bid was a very smart piece of work, masterminded by former Creative Scotland chief executive, Andrew Dixon. While the Dundee bid had a self-congratulatory air, Hull’s pitch was grounded in grassroots engagement and built on a strong city-wide partnership. One of its most striking features – highlighted by the judges - is the way in which the 2017 programme will use and celebrate places in this remarkable but undervalued city. For example, the Looking up festival will select 52 buildings, spaces and landmarks to be featured in week-long “surprise commissions” featuring light, sounds, words, film and live performance. Flags, Wind and Waves by Angus Watt will use hundreds of flags to delineate the city’s neighbourhoods, boundaries and river frontages.

This theme of working with the city and its communities was sound in principle and tactically astute. Hull has not burdened itself with a massive capital programme, although there will be some investment in venues and other facilities. What’s promised is a celebration of the city as it is – a singular place with a rich history and built heritage. The challenges facing Hull are well-known: it is at the bottom of almost every available league table of socio-economic performance, and the city’s problems were compounded by the catastrophic floods of 2007 which overwhelmed the drainage system and flooded 8,600 homes and 1,300 businesses. Hull is seen as a struggling city, caught on the wrong side of history and, too often, badly managed.

So it is good to report that a visit to Hull is, in almost every respect, a delight. It is true that there’s nowhere decent to stay, although a new Radisson hotel is promised, eating out isn’t great, and the shopping offer is at best workmanlike, but a couple of days spent in the city will still be hugely rewarding.

You approach, as you must, from the west, beside the Humber, miles wide at this point, and the place (to quote Larkin) “Where sky and Lincolnshire and water meet”. The train passes under the magnificent suspension bridge and then (Larkin again) “…the widening river’s slow presence/The piled gold clouds, the shining gull-marked mud,/Gathers to the surprise of a large town:/Here domes and statues, spires and cranes cluster/Beside grain-scattered streets, barge-crowded water”.

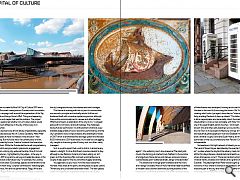

The streets are no longer grain-scattered and the rivers aren’t barge-crowded. Most of Hull’s maritime trade has shifted to modern docks further downriver, but the presence of the historic port is still felt everywhere. In the 19th century a series of linked basins was developed, forming an arc that linked the Humber to the river Hull, encircling the historic Old Town and creating what Larkin (yet again) described as “a terminate and fishy-smelling/Pastoral of ships up streets”. The historic centre is still a magical place, and remarkably intact: the medieval street pattern is more or less complete, with Holy Trinity – one of the great English parish churches – at its heart. Some ancient inns and other early buildings survive, but the glory of the Old Town is its Georgian architecture, lovingly chronicled and beautifully photographed in Ivan and Elisabeth Hall’s 1978 book. Another couple, David and Susan Neave, are the leading authorities on the city’s architecture: their Pevsner City Guide is indispensable.

Somewhere in this tight network of streets you will find The Land of Green Ginger, described by the poet Ian Parks as “…a place where the sky/and the estuary meet;/where all the thin alleys/deceive, double back/and lead to a spot/where strangeness occurs”. There are handsome brick houses, Victorian banks, arcades and markets and a grand Edwardian Guildhall. The playwright Alan Plater was brought up (though not born) in Hull, where he worked in an architect’s office. He loved this part of the city and wrote about it, rather improbably, in an essay for the 1962 Port of Hull Journal which celebrated a place where “commerce, recreation, ships, big business, shopping and civic administration all intermingle”.

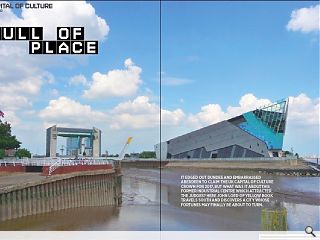

The Old Town is separated from the Humber waterfront by a dual carriageway which carries port traffic through the city. The effects of the road are predictably disastrous and they have had a chilling effect on attempts to revive the atmospheric but decayed former fruit market area, which is slowly evolving into a cultural enclave. Also stranded on the wrong side of the A63 is The Deep, a hugely popular visitor attraction with a frustratingly semi-detached relationship to the city. It won’t be easy, but Hull needs to heal the rift caused by the road: until it does, it will never be the place it might be.

The Deep, a splendid aquarium designed by Terry Farrell, is the epitome of old-school 1990s iconic architecture, and it is a source of much pride and affection. Its stealth bomber aesthetic is echoed in a more recent project, McDowell + Benedetti’s Scale Lane Bridge.

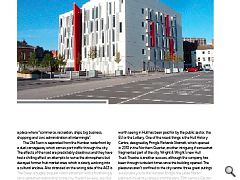

It’s not my favourite thing: a bit too tricksy and over-engineered for a no-nonsense place like Hull, but it’s fun and the pocket park they have created on the left bank of the river is delightful. In fact, just about everything that is new and worth seeing in Hull has been paid for by the public sector, the EU or the Lottery. One of the nicest things is the Hull History Centre, designed by Pringle Richards Sharratt, which opened in 2010 in the Northern Quarter, another intriguing if somewhat fragmented part of the city. Wright & Wright’s new Hull Truck Theatre is another success, although the company has been through turbulent times since the building opened. The pleasures aren’t confined to the city centre: three great outings would take you to the Humber Bridge, the Leslie Martin-planned University campus and the early 20th century Garden Village.

Hull is an ideal choice for City of Culture. It is a city struggling with daunting, systemic problems but it is far from the woebegone basket case presented in a recent Economist article. The city has a remarkable history, a rich cultural life, creative talent and a tradition of social entrepreneurship. The idea of using the 2017 programme to celebrate and showcase Hull’s rich and stimulating sense of place, its communities and neighbourhoods is very exciting. It won over the judges and it should make Hull’s tenure as City of Culture something quite special.

|

|

Read next: Fashion & Architecture

Read previous: Solar energy for Scotland

Back to April 2014

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.