Derelict Glasgow

15 Apr 2014

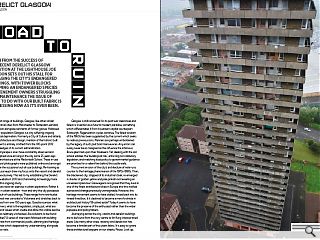

Flush from the success of the recent derelict Glasgow exhibition at the Lighthouse Joe Shaldon sets out his stall for salvaging the city’s endangered buildings. With tower blocks becoming an endangered species and tenement owners struggling with maintenance the issue of what to do with our built fabric is as pressing now as it’s ever been.

With a vast range of buildings, Glasgow, like other similar post-industrial cities from Manchester to Rotterdam exhibits regeneration alongside remnants of former glories. Hollowed out by de-population Glasgow is a city suffering ongoing major social deprivation. Formerly a City of Culture and latterly City of Architecture and Design, mention of the historic built environment is entirely omitted from the 100-point 2012 election pledges of its current administration.This cityscape is one I have constantly observed and photographed since arriving in the city some 25 years ago to study architecture at the Mackintosh School. These in-use architectural photographs were published online and amongst them were the occasional out-of-use buildings. Re-training as a building surveyor drew my focus onto the vacant and derelict buildings exclusively. This led to my establishing the Derelict Glasgow website in 2010 and channelling increasingly more time into this ongoing study.

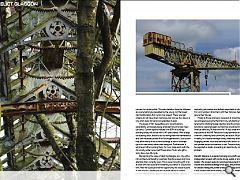

This was never an exercise in urban exploration. Rather it is a study in urban isolation - how and why the city possesses so many out-of-use buildings. These range from new-builds through post-war concrete to Victoriana and stretches back to farmhouses from over 150 years ago. Questions arose: what are the drivers, what is the legislation, simply put, what are the myriad of issues which create and allow this visible decline to progress relatively unchecked. Are solutions to be found in other cities? A series of interviews followed with building professionals from commercial, public, planning and heritage backgrounds which deepened my understanding, alongside regular site visits.

Glasgow is still renowned for its post-war clearances and failed re-invention as a futurist modern paradise, something which differentiates it from its eastern capital counterpart Edinburgh. Regeneration cycles continue. The failed wisdom of the 1960s has been supplanted by the current which seeks to redress previous sins. Planners are perhaps emboldened by the legacy of such past bold manoeuvres. Any errors can surely never be as maligned as the influence the infamous Bruce plan had upon their forebears. Yet, dealing with the old school estates, the ‘buildings at risk’, enforcing non-statutory legislation, and matching local policy to governmental guidance are priorities for a valiant few behind the castle walls.

The current erosion of the city’s architecture of note runs counter to the heritage phenomenon of the 1970s-1990s. Then, the blackened city, stripped of its industrial cloak, re-emerged in shades of golden yellow and pale pinkish red revealing an unrealised splendour. Glaswegians recognised that they lived in one of the finest architectural cities in Europe and this instilled a pride and change previously unimaginable. However, this heritage movement seems to have stalled, forced back into its tweed-lined box. Is it destined to become a mere footnote in architectural history? Brushed aside? Today it seems to have become the preserve of the enthusiast rather than the wider populace and policymakers.

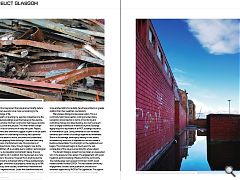

Journeying across the city, vacant and derelict buildings are to be found from the very centre to far flung impoverished areas. Like many other cities, vacancy and dereliction has become a familiar part of the urban fabric. It is easy to ignore these architectural beggars on our streets. Pause. Look up, and think. One may lament their predicament briefly, before averting one’s eyes and once more surrendering to the constant charge of life.

For myself, not averting my eyes has instead become the habit. Decaying buildings reveal themselves as they decline, creating a window into their construction techniques, and also their history, social and physical. This often reveals a single building is in fact a continuum of many life cycles. Repairs, refurbishments and extensions suggest its path is not yet spent. My own reason for undertaking this study was a personal passion and a desire to record, document and understand. Whilst photographing these buildings, it became clear many were listed and of architectural note. Once lynchpins of their neighbourhoods, many, through neglect, now do the opposite. Written off as unviable due to isolation, technological redundancy, de-population and rampant decay, they are sealed and left to rot. In isolation, this may be seen as a mere financial loss to the owner. However this is anything but the case. Allowing the unchecked rotting of these isolated assets creates blight, diminishes local property values (by up to 18% as indicated by some studies), undermines investment and depresses neighbourhoods. Locals feel disenfranchised and a democratic deficit can be seen to be taking place. The more impoverished districts inevitably face these problems in greater isolation than their wealthier counterparts.

Many believe listing provides preservation. This is a commonly held misconception. Listing provides status, recognition and protection in terms of monitoring and controlling changes to a listed building. As a tool to prevent loss it is largely toothless as evidenced citywide. Buildings legally require no equivalent of an MOT, buildings insurance or maintenance cycle. Listing demands no such increased demands upon owners of buildings regarded as remarkable. Storm or fire damage, bankruptcy leading to toxic assets, unsatisfactory resolution of dilapidations can also render a building untenentable. Thus the blight on the neighbourhood begins. This article just begins to touch upon the vast complexities of the issues surrounding this whole subject.

The Derelict Glasgow project has now taken an unexpected turn in the exposure it has gained. The engagement with social media has led to increasing influence from the community. The website page views exceed 10,000 per month, social media followers number 3000+. This has created community engagement, funded a book publication, and led to an exhibition supported by A+DS at The Lighthouse. This support indicates the erosion of our built environment is of great concern to a wider public. The web statistics show the followers are overwhelmingly populated by the young, not the tweed clad traditionalists that cynics may expect. These younger citizens do not have direct memories, but can see the value in a city which looks forward and celebrates its past.

The issues of VAT inequalities, zero-incentivisation, sutainability, embodied energy and blight are amongst major concerns. Current reports indicate over 80% of buildings standing today will still be with us 40 years hence. With a large old building stock, failure to act to reinvigorate the maintenance and care necessary bodes ill for future generations. Such action may allow many of the current buildings at risk to be swept up in this new wave, rather than being lost. Furthermore, it will prevent others joining them. For now, hope exists with the chronically under-resourced Preservation Trusts who gift a lucky few a new life cycle.

Recognising the value of retaining Glasgow as a city with a rich architectural tapestry is perhaps therefore deserving more attention than currently given. This is never to be thought of as at odds with new build and modernity, but rather in conjunction with. New life cycles provide the opportunity for radical fusions of new and old. Addressing the citywide decay in a more positive manner offers opportunites, sustainability, carbon neutrality, job creation and skillsets exportable to other cities. For communities it links them with their histories, helping to assure their futures.

Finally to those who becry recession, it should be remembered saving the Merchant City, refurbishing the tenements, initiating façade retention and the wholesale sandstone cleaning began during times of extraordinary financial difficulty. At that time the UK was under the impositions of the IMF. Recession today demands radical re-invention, creativity and community led action. Much funding is in reality, for instance heritage lottery, relatively recession proof. Engaging debate, local and national public sector co-operation and private sector involvement is vital. These buildings should be regarded as assets, presenting an opportunity, rather than a problem.

Derelict Glasgow is an award-winning non-profit, self-funded independent project with no ties to any public or private bodies. The project seeks to record and document Glasgow’s vacant and derelict buildings of all ages, and provide a forum for debate raising the profile of these ‘buildings at risk’. It is a solo project with all recording, photography, design and research undertaken by the founder: Joe Shaldon.

|

|

Read next: Minecraft

Read previous: Practice Management

Back to April 2014

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.