Cowgate

15 Apr 2014

The newest corner of Edinburgh’s Old Town has been 12 year’s in the making, but has it been worth the wait? Urban Realm paid a visit to the historic site to find out if its belated Lazarus rise from the ashes does justice to Robert Adam’s legacy - or is an opportunity missed.

Undergoing many guises as a succession of architects and developers picked up the baton on a tortuously circuitous route to fruition it was ultimately ICA Architects and Jansons Property who first crossed the finishing line. Appointed relatively late in the design process, just three months before planning, and caught in a pincer movement between a frugal funding environment and all-powerful heritage lobby ICA were left with little room for manoeuvre in their delivery of the £30m scheme, which includes the 259 bed Ibis hotel and retail units fronting South Bridge. It incorporates internal pedestrian links linking South Street and Chambers Street and reinstates the jazz club La Belle Angele and hallowed Fringe venue the Gilded Balloon.

Shorn of some of its more exuberant bells and whistles, such as a giant glass dome, during a lengthy gestation, what has been built is a somewhat anodised mirror image of a Robert Adam tenement. This matches the scale and materiality of its neoclassical neighbour but brings little else new to the table, although it does benefit from a livelier façade further down the Cowgate with some jaunty set-backs and openings which break up the monotony of stone to invite pedestrians to climb up through the site.

If the exteriors are plain then the interiors are invisible, with everything from hotel blinds to desks, benches and wardrobes conforming to the Ibis brand template. Even the artwork is corporate standard issue. A Sainsbury’s supermarket and Costa Coffee are of course nothing to write home about either. Taking Urban Realm on a guided tour project architect Kerry Acheson explained: “The interior design is an Ibis standard, only the public areas were done by ICA and these are designed more for Edinburgh people with Scottish themes and parts of the city in them.”

The hotel succeeds in marrying new build with historic elements although again not without some glaring compromises to keep the client happy. Thus the existing full-height windows are retained – including one accidentally broken and painstakingly restored – but with a perverse suspended ceiling added as per the Ibis rule book. Acheson noted: “It’s an Ibis standard that the ceilings can’t be too tall, but obviously you do have the taller windows so it’s a compromise between the two.” High specification windows are a feature throughout the build which has to contend with the worst vibration and noise which South Bridge can present, a job which it accomplishes remarkably well so that even the most insomniac of guests is unlikely to be troubled by the passing of the number 35 bus.

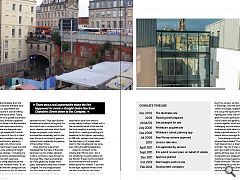

A key planning requirement stipulated that the mass of the hotel be broken up into smaller elements to allow continuous views through to the Royal Mile, a feat accomplished by a fully glazed sky bridge which spans a precipitous drop over a distant Cowgate. The sky bridge doubles as a lofty means of entry and exit as well as providing an arresting observation deck from which to survey nearby rooftops. Indeed such is the convoluted nature of the site that the front reception is actually on the fourth floor… creating something of a headache for fire fighters responding to 999 calls.. perhaps ominously given the sites history. It’s a steep climb down to the Cowgate and vice versa, even without breathing apparatus.

Asked to comment on the scheme Allan Murray said ‘…this is not something I would be able to do’ but Malcolm Fraser, the first architect to be involved with the scheme following the fire, recalled: “I did work for the eight separate owners of the site with proposals for the Gilded Balloon and La Belle Angele. When it burnt my concern, as often happens in Edinburgh, was that each of the owners would get a separate lawyer and use up the equity of the site in fighting each other over ownership. I spent two years getting all the owners round a table and agreeing on how to work together, which was quite challenging as some were pukka and institutional, while others were slightly shady nightclub owners. There was a natural distrust amongst them.”

Commenting on the delivered scheme Fraser added: “The fantastic multi-layered site is a dream for any architect. The mix of uses is great and I give credit to the developer for getting all these uses on site - but its elevations are disappointing.” Outlining a missed opportunity Fraser continued: “We’d proposed demolishing the curved corner building on Chambers Street to expose one of the existing gables and that would have recovered the footprint of Adam Square. You would then have got a public space opening up the close, building a new hotel to that end of Chambers Street quite a bit higher to compensate for the space lost. There was a real opportunity when the fire happened to create a straight desire line from Chambers Street down to the Cowgate.”

A condition of planning was that an access gate to the internal pedestrian route be locked between 11pm and 7am with Acheson conceding that the Cowgate is ‘not very pleasant at night.’ Cognisant of this fact the hotel’s duty manager was also decidedly unenthusiastic at the prospect of strangers milling around in the dead of night. Within this space are a number of artworks peppering a central square which will house an outdoor café/bar space in the summer. Gazing at a dramatic chunk of twisted metal, a collaborative sculpture designed by four young artists; Jim Shepherd, Dominic McHenery, Angus Ogilvie and Tom Brown, Acheson said: “It’s based on the old arches which were down on Cowgate. The angles are based on the views into the site and the arches which used to be here.”

Connecting spaces are given solidity by extensive use of stone such as granite and Caithness blocks, another planning requirement, which provides a durability that will doubtless come in handy when the teeming hordes of Festival-goers descend upon its steps. Sadly the whole space is overlooked by the distinctly unloved rear-end of a University of Edinburgh building over which the team have no control.

Happiness at having completed the marathon build was tinged with sadness following the death of the developer’s son, Alexander Janson, who passed away suddenly during the build and whose name the new building now takes. Building a city is a marathon not a sprint but in the global race for wealth of which we are participants (willing or not) the glacial pace of progress on key schemes such as this casts doubt on Edinburgh’s ability to up its game in the face of an increasingly dynamic global economy. If the Cowgate serves to focus minds on breaking the planning logjam and stifling architectural straightjacket for future builds then it may have been worth these long years of waiting. Otherwise it simply fills a space, and leaves you feeling somewhat unfulfilled for that.

|

|

Read next: Glasgow School of Art

Read previous: Architectural Photography

Back to April 2014

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.