Cecil Balmond

15 Apr 2014

Star of Caledonia designer Cecil Balmond has found himself at the heart of the debate around the nature of Scottish identity as the independence referendum looms. Following publication of his new book, Crossover, Urban Realm caught up with the Sri Lankan/British designer to find out more about the creative process. All photography taken from Crossover, published by Prestel.

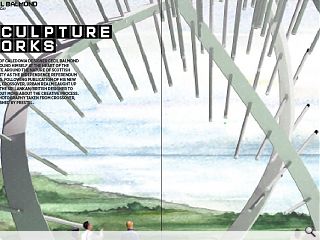

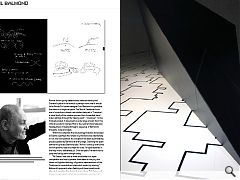

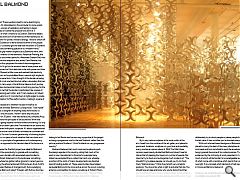

Amidst the on-going debate about national identity and Scotland’s place in the world it is perhaps ironic that it should fall to British/Sri Lankan designer Cecil Balmond to symbolise the nation in a single set piece. The Star of Caledonia forms one of more than a dozen case studies featured in ‘Crossover’, a visual study of the creative process from the earliest hand drawn jottings through the ‘tipping point’ - ‘Crossover’ - to the finished product. It documents a wide range of work from The Orbit at London’s Olympic Park to the Central China Television Headquarters in Beijing through a sequence of Balmond’s thoughts, notes and ideas.Within this collection the structural gymnastics showcased at Gretna is perhaps the richest in symbolism and, intentionally or not, the most political. Its conception has been a painstaking process guided by Balmond at every stage. Outlining the spark behind this process Balmond said: “At first I come up with some kind of dynamic idea and shape for a site. I’m quite abstract in the way I work, deliberately so. Over the years I’ve learnt not to jump and be figurative straight away.

“At Gretna I was one of three shortlisted in an open competition and had to present three ideas to the jury, one based on Highland dancing, a figurative representation of the Thistle and a more abstract idea which ended up winning.” Balmond’s approach when fleshing out these broad-brush ideas is to question the design at every stage. “Is it heavy and dense, or perforated? What are the features I want from it?” Balmond said. These questions lead to some sketching by hand before it’s rationalised on the computer to some extent, allowing the process of realisation and testing to begin.

In the case of Gretna the proposal was born of a questioning of what it means to be Scottish. Balmond added: “The piece has some sort of semblance of that identity but it’s also a metaphor for power, wind and energy. I tried to switch off my ideas of Scotland in a literal sense and think of the people I’d met there. I suddenly got the idea that the brains of Scotland had contributed something special to our modern world.” Amongst the grey matter singled out by Balmond were John Logie Baird, inventor of the television, Alexander Fleming, the biologist who discovered penicillin, Alexander Graham Bell, who developed the first telephone andJames Clerk Maxwell, the physicist who first proposed the idea of electromagnetism.

“I thought I’d go for the abstract idea of brain power and the enlightenment so I first sketched a star with power and then I thought of Maxwell a little more and realised that electricity and magnetism, as he postulated them, were at right angles to each other in wave form. I then thought of the border as being perforated, it is not one hard line but rather a boundary that can be crossed in many ways. A local farmer takes a short journey across it while a businessman takes a much long journey. So the idea grew on me that the border is perforated, like a series of waves overlapping each other and if I can create an art object that has waveforms in it I can site them at right angles to create a kind of metaphor for Maxwell’s invention, making it a piece of discovery.”

When pressed as to whether he sees himself as an engineer or an architect Balmond is unequivocal. “I see myself as a designer, a designer of anything really from books, to architecture and structures. I haven’t done any structural engineering for 20 years - that was done by my company Arup. but I understand the principles of structure and I think that helps a lot in going beyond normal architecture training. It’s only in the last five or seven years that I’ve entered the art scene and become involved with public sculpture. It’s about organisational principles, structure is one of them, architecture is another and music a third. For me it’s more a general way of showing rhythm and dynamics in a piece of work whether that be a book as in Crossover or in principles of organisation and contemporary ideas of flux as opposed to the classical idea of the frame as a border. “

In that sense the Scottish project was ideal for Balmond, who relished the opportunity to grapple with something as intangible as a border with associated opportunities to make a significant statement on the landscape, something Britain as a whole has gotten rather good at in recent years as witnessed by the aforementioned Orbit and even Andy Scott’s recently unveiled Kelpies at Grangemouth. Acknowledging this backdrop Balmond noted: “it began with Antony Gormley and the Angel of the North. It’s not easy; there are a lot of bad examples in the world, but I think Britain’s done well. I was talking to Ian Rankin and he was very supportive of this project as being a progressive one for the real Scotland, rather than the picture postcard Scotland. I think Scotland is a very progressive country. “

Balmond believes that much more can be done to push the design agenda in this country, noting that much of his work is now international. In America for example many states have adopted the so-called 1 per cent rule; whereby a portion of the costs of major developments are diverted toward funding public art. These opportunities have helped persuade Balmond to be more active across the pond, including entering a competition to design a sculpture at Folsom Prison, immortalised in a live album by Johnny Cash. “We don’t have the same rules in Britain but it does help artists,” observes Balmond.

By its very nature sculpture is the most public of the arts, freed from the confines of the art gallery and placed in prominent locations, sculpture is in your face and inevitably every one has an opinion about it. With The Orbit those opinions were heavily divided but Balmond doesn’t see his role as that of pleasing the maximum number of people. Nor does he try to shock and outrage like much modern art. “You shouldn’t try to please people, nor should you try to shock them,” Balmond says. “I think they’re both very simplistic positions. You should do what is right to activate that site. You should have an idea and know why you’re doing it but then you should do it true to its own integral values. Some will like it and some won’t but it provokes debate around the work. If you deliberately try to shock people or please people the work is of limited value, it dies out after you’ve shocked everyone. “

With such a broad based background Balmond is well placed to marry the best of the many disciplines at his command and he is not afraid to push the envelope to avoid being typecast like some of his contemporaries. This is evidenced by the rich body of work presented in Crossover, much of which will be familiar to knowledgeable readers but all of which come with a narrative which paints their delivery in a new light. It is a concept which demands a fresh approach and in Crossover Balmond delivers it.

Crossover by Cecil Balmond, published by Prestel,

is available now priced £40.

|

|

Read next: Union Street

Read previous: Fashion & Architecture

Back to April 2014

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.