Scottish Civic Trust

13 Jan 2014

The Scottish Civic Trust is seeking to drive bottom-up engagement with communities by adopting some new tricks to tackle old problems. Chief amongst these is ensuring that Scotland’s small towns ‘stay special’ by maintaining links to their past in a world experiencing exponential change. Here the civic movements director, John Pelan, outlines how this can be achieved.

It seems that Scotland is awash with built environment related policies just now. Planning reform, a new architecture policy, a town centres review and an imminent historic environment strategy are just part of the Scottish Government’s cross-cutting policy mix. These are ambitious too, in terms of mainstreaming the built environment, historic and contemporary, across different departments in national and local government; simplifying and speeding up the planning process; and devolving power and decision making to local communities. Throw the Community Empowerment Bill and the big issue of asset (or is it liability) transfer into this policy stew and what do you get? Better buildings and places is the desired result.The placemaking agenda, which sits at the heart of much of these interconnected reviews, is also being driven by an overriding priority for the Scottish Government – that of sustainable economic regeneration. Whether the two outcomes are compatible is still to be resolved but there is no doubt that there is a genuine attempt by politicians to evolve a culture of joined-up thinking to improve the standard of our buildings, places and spaces.

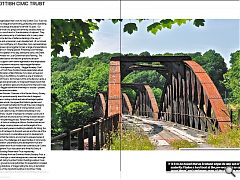

I can accept that placemaking is about creating high quality places for living and working but I often wonder if, as a nation, we should be more concerned about place protection. Scotland is a country of small towns, many of which have suffered from decades of investment blight, poor planning decisions, and too many appalling buildings. Places that once had a distinctive identity, defined by their 18th or 19th century plans and intelligently evolving architecture over several centuries, are in danger from a sustained erosion of their fragile relationship with their past. Travel to towns like Montrose in Angus, Peebles in the Scottish Borders, Castle Douglas in Dumfries and Galloway or Campbeltown in Argyll and Bute and you will find a recurring theme – a struggle to preserve the dignity and integrity, forged in a different era of civic pride and social responsibility, which made these places special. Historic buildings, many of them listed, are in danger from neglect and underuse or, worse, lying empty and at risk. Pressures from housebuilders and supermarkets, not minded to being fettered by conservation or design agendas, is returning. Local authorities are struggling with slashed budgets. Expertise and resources needed to maintain and protect the architectural integrity and heritage of our towns are, if anything, shrinking.

Against this arguably over-negative background we should and must engage positively with the Scottish Government’s attempts to tackle the big problems in planning, heritage management and placemaking. The aspiration to empower local communities to have greater responsibility for their places should be encouraged and supported as is the ambition to mainstream the historic environment beyond the desk of beleaguered conservation officers.

The organisation that I work for, the Scottish Civic Trust, has been at the vanguard of promoting, protecting and celebrating Scotland’s buildings and places for almost 50 years. Our network of local civic groups and amenity societies share our aspirations, one of which is ‘the elimination of ugliness’. They are a largely unsung army of volunteers who, in many cases, have been the last line of defence standing in the way of aggressive and unnecessary over-development. At our annual conference in Linlithgow on 5 November, many representatives of these groups came together to hear a range of presentations on the theme of ‘Staying Special: Protecting Local Heritage’.

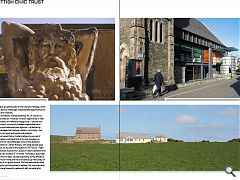

The first speaker of the day, setting the scene, was Derek Mackay, Minister for Local Government and Planning. The Minister talked about the need for grassroots decision-making to support town centre regeneration and emphasised that planning reform was about improving performance but not at the expense of quality. Maggie Broadley, Chief Executive of Craft Town Scotland spoke passionately about the transformation of West Kilbride, from down-at-heel and deteriorating in the 1990s to its rebirth as one of Scotland’s official Craft Towns. At this heart of this is the Barony Centre, a refurbished and dynamically re-imagined B-listed church that provides an exhibition space and focal point for the town’s new industry. Maggie outlined her three keys to success – passion, perseverance and innovation.

Dr Peter Burman, Chairman of the Garden History Society in Scotland, spoke eloquently about the role of designed landscapes in uniting cultural and natural heritage together in a seamless whole. He argued that historic gardens and landscapes should be treated as though they were Category A listed buildings. Stuart West of Orkney Islands Council talked about a pilot survey of traditional buildings in one parish – Birsay - as part of a project to compile a Local List of all important built structures across Orkney to assist decision making in the planning process. Ranald MacInnes, principal inspector of historic buildings at Historic Scotland tackled our future heritage, covering issues such as the length of time needed to properly assess a building’s suitability for listing; the expansion of heritage into the post-war era; and the role of the historic environment in sustainable economic development. He argued that the historic environment is a layered series of interventions. The challenges and opportunities of community-led regeneration presented by the development trust and building preservation trust models were outlined by Ian Cooke of Development Trust Association and Anne McChlery of Glasgow Building Preservation Trust respectively.

Luke Moloney from the Dumfries Historic Building Trust, a veteran in the fight to save heritage assets, said that, although an excellent policy to protect historic buildings existed, it was too often ignored by local authorities. His presentation included a sobering slideshow of images telling the story of demolition of so many of the important buildings in Dumfries. Finally, Simon Green, chairman of the Architectural Heritage Society of Scotland, gave an uplifting talk on the future for heritage, which despite the obvious challenges, still presented opportunities for celebration and creativity.

Did the conference change anything? No, of course not, conferences rarely do. However, it was an opportunity to hear a range of voices from different backgrounds – national and local government, community heritage organisations and regeneration and redevelopment agencies – all delivering the same messages that heritage matters, community - led regeneration can work and people make places.

It is to be hoped that as Scotland edges its way out of austerity it takes a cold hard look at the pre-recession so-called ‘good times’ and challenges some of the decisions made. My old boss, Charles McKean, who sadly passed away in September, hit the nail on the head in his 1977 book: “Fight Blight: A Practical Guide to the Causes of Urban Dereliction and what People can do about it” He wrote: “Ironically, a good deal of the mess has not been caused by poverty, but by affluence. We had so much money that we soon picked up many ways of mis-spending it in a grand manner. We have demolished what was often good, and attempted to replace it by improvements. Instead, we have frequently replaced it with something far worse”.

|

|

Read next: Aerostatic Bloomage

Read previous: Wasteland Collective

Back to January 2014

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.