Wasteland Collective

8 Nov 2013

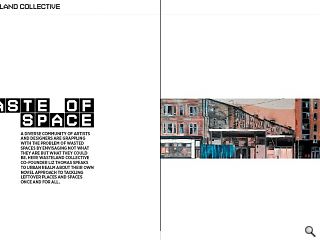

A diverse community of artists and designers are grappling with the problem of wasted spaces by envisaging not what they are but what they could be. Here Wasteland Collective co-founder Liz Thomas speaks to urban realm about their own novel approach to tackling leftover places and spaces once and for all.

As adverse economic conditions taking their inevitable toll on our landscapes there has never been a better time to re-appraise our relationship with the scraps of land which have fallen through the cracks in the economy; from litter strewn verges to unloved backcourts. Exploring the issue of what wastelands are and,more importantly, what they could be is an organisation called the Wasteland Collective, which recently staged an exhibition displaying a varied body of work from artists and designers who seek to promote the life and public potential of such spaces.Explaining the concept to Urban Realm Liz Thomas, founder of the collective, said: “At its core, the collective is a group of landscape architects looking for a way to put our discipline to more dynamic effect, and to work collaboratively to offer up ideas for what wastelands could be. We aim to address the growing number of people concerned by wasted space in cities, people who acknowledge the value of urban land and know it can do more. The project aims to pull together a community of interest, and document how we can collectively raise the bar of what can be expected.”

To achieve this the group work collaboratively with a wide variety of contributors, using this as a platform to “celebrate anything from permanent interventions to temporary landscape projects, to fleeting momentary events – anything which gets people thinking about how they could make better use of the precious resource of urban land”, says Thomas, who adds. “We work with young creative practitioners: artists and community growers, filmmakers and storytellers, people who like to build and people who like to demolish. To come up with fresh approaches to landscape architecture in response to today’s needs and aspirations.”

But surely rather than working with wasted spaces efforts would be better targeted at preventing such spaces from arising in the first place? Thomas answers: “There are a number of reasons for the existence of urban wastelands. It should be noted, that by ‘wasteland’ we refer not only to the vacant and derelict brownfield sites, but to every leftover, residual, underused and wasted street and space of the city. Of these, some wastelands are a result of a function being lost or taken away from a site. This site or space may then not have had the function replaced and thus becomes a wasted area of land in the city context. Another reason wastelands develop may be due to poor planning and functionality. If an area is designed specifically for one purpose it can preclude more dynamic and varied uses of space: the usability of the space is limited.

“To prevent the formation of wastelands we think we can look again at how we plan our city spaces and consider options for a more multi-functional and flexible planning approach. In support of a more multi-layered planning approach, quality community consultation is critical to the design and planning of our cities. We think that public space needs to be defined by the local people whilst meeting their needs and demands. This ensures there is a will and an involvement in the function and offer of the urban environment. It is true. even in the planning of urban lands, that ‘form follows function’: the function of the land must be guided by the people who live there while the space’s form may shift and change.”

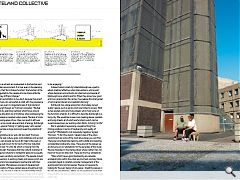

Mark Twain’s exhortation to buy land, because they aren’t making it anymore, sits somewhat at odds with the prevalence of wasted spaces even in congested areas of high demand such as Edinburgh though, as Thomson concedes: “We feel that traditional city planning methods which focus around zoning and site allocation are a hindrance when addressing the problem of residual or resultant urban space. The lack of cross-over when planning areas of our cities can result in left over space that has a low social value and lack of energy. Edinburgh is a city that is good at ‘hiding’ or ‘getting away’ with wasted spaces but if we take a closer look and reveal the potential of our urban land.”

Describing Edinburgh as ’just a bit too staid’ Thomson believes that the real culture, grass roots initiatives and up and coming artists can actually be found 40 miles to the west, in Glasgow, a city well known for its tracts of former industrial land. Thomson said: “It is this life which is missing from the streets of Edinburgh. We believe that the cultural character of Edinburgh requires solutions to wasteland space to be equally balanced between sensitivity and activism. The people should demand interventions in existing streets and spaces which are well considered and are developed in partnership with their needs and interests. We believe a process of development and re-appropriation of these wasted spaces should be a high priority for the city council in order to compliment the historic fabric of the city: intervention for positive change and bringing wasted space to life doesn’t need to be drastic but it does need to be engaging.”

Instead historic small city’s like Edinburgh are urged to adopt small but effective urban interventions, until a point where designers and activists can step back and people of Edinburgh know what to ask for. When they know how good and how varied urban life can be, if we release the strait-jacket of commercial interest and capitalist planning.”

Edinburgh has a large proportion of privately owned ‘public’ spaces such as parks which are limited in access. With so few pocket parks and living streets which host some of the functions of parks, it is difficult to describe Edinburgh as a living city. We would like to see more meeting places, parklets, and living streets, all of which are functions which can be superimposed over our existing urban fabric, to bring it to life.”

But is wasteland necessarily a negative thing? Can it bring positives in terms of biodiversity and quality of amenity? “Wasteland is not necessarily negative,” agrees Thomson. “In fact the vacant / derelict sites of the urban environment are some of the most alive places you can find. There are brownfield sites teaming with wildlife and boasting considerable biodiversity value. These are not the spaces we are focusing on as ‘wastelands’ for the purposes of this study. We are interested in the sterile: places where neither man nor flora nor fauna can take root. These are the true ‘wastelands’.

“Sites which have a good biodiversity are valuable ecological sinks within the urban environment, and any future proposals needs to carefully consider management of the existing plant and animal species. We are not necessarily looking for the over-design of any space - breathing spaces in the city are essential too - rather we are seeking to inject a bit of life whether for man or nature within the concrete-clad core of the city.”

|

|

Read next: Scottish Civic Trust

Read previous: Fountain Quay

Back to November 2013

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.