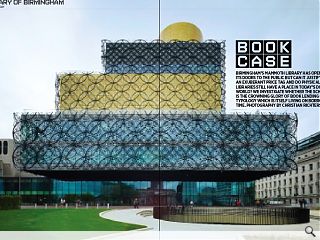

Library of Birmingham

23 Oct 2013

Birmingham’s mammoth new library has opened its doors to the public but can it justify an exuberant price tag and do physical libraries still have a place in today’s digital world? We investigate whether the scheme is the crowning glory of book lending or a typology which is itself living on borrowed time. Photography by Christian Richters.

Francine Houben, founding partner of Mecanoo (currently working on a master plan for Clyde Gateway), told Urban Realm: “I bought a travel guide to the UK and Birmingham is just two pages in it. Can you imagine that, for the second city? Birmingham has a very rich history. We were aware of the famous Jewellery District which has a tradition of craftsmanship which still exists today.”

The arrangement of functions within the building pays cognisance to this by placing the single most important element, the archives, not in the lower ground floor or the cellar but high in the showpiece Shakespeare Memorial Room, which has been painstakingly reassembled from the original Victorian library. This allows the greatest flow of people, around 10,000 a day, on the lower and most popular floor which extends out to embrace the palazzo thus bringing the library into the public space in the form of an ‘outdoor amphitheatre’, directly accessible from the lower ground floor by way of giant sliding doors.

Already it is a popular spot for children’s sleepovers and concerts, as Houben attested: “The idea was you walk by in the street and you hear the piano playing, when we had the topping out ceremony we had people performing Shakespeare in this space. It’s very focussed but also informal and reflects Victoria and Chamberlain Square. We really try to promote the informal performing arts. Canopies allow people to sit outside on the southern end of the square, drawing the northern light. As soon as it’s nice weather everyone is sitting outside, even in winter time they wear clothes that are very thin.”

Centenary Square sits on top of the highest hill in Birmingham and the Shakespeare room takes pride of place above that, affording it a commanding presence on the skyline and giving it visibility from across the city. “The gold archive fits in the tradition of Mecanoo but also it’s a golden box for the archive, it is precious. This is about showcasing something which normally would be hidden,” notes Houben. “Birmingham is very hilly, but it’s also very green, just not in the city centre. There it has many grey roofs so we wanted to make our terraces very green, like elevated parks.”

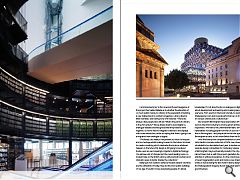

Internally the library is defined by a sequence of rotundas emanating from the main reading room, an events space on five levels events space traversed by escalators and travelators. This serves to connect the public library with a discovery terrace and research library and forms a key component of the sustainability strategy by helping to drive ventilation in the BREEAM excellent building. Explaining the science behind this process Patrick Arends, associate architect at Mecanoo added: “An over sail allows air into the space and as warm air rises it introduces a stack effect through the building. Internal spaces, were intensively modelled in partnership with Buro Happold to keep the velocity of air optimal. Wherever you are you always have views through, it’s an ode to the book.”

These rotundas also continue the circular rhythm which is evident from the stylised frieze which wraps around the façade. Houben observed: “The frieze is the most striking feature, it shows the changing light 365 days a year and changes depending on the moment of the day or the season. We can keep the lighting white and at special moments be expressive with reds or greens at Christmas to become part of the market. What the circles and shadows mean for the interior is about creating your own panorama.” The craftsmanship evident in the interlocking metallic circles is also evocative of the steel and jewellery industries with the enigmatic façade deliberately left open to interpretation by visitors.

Continuing the tour through a series of spaces defined by their use of natural stone, white ceramic flooring and oak Arends nodded to the blue, gold glass and metal features and said: “You can find your own space in the building, watch things happening; sit around the rotundas, everywhere has the same light, with light wells sunk through the terrace. It’s a raised floor but it feels solid and has flexibility to adapt in future. 25 per cent of youths in Birmingham do not have access to internet at home, so the library has become an important access point.”

Commissioned prior to the recession the extravagance of the project has fuelled debate as to whether the allocation of so much public money to a library is the equivalent of building a new stables block to combat congestion. Library director Brian Gambles, was having none of it however: “There are always a few people who will ask ‘What’s the point of a library in the 21st century?’ We’ve always tried to avoid digital vs. analogue debates and recognised that they need to work together. So we’ve tried to integrate collections and displays with online interaction, whilst accepting that there’s going to be a migration from analogue to digital.

“The library sits neatly in the present but looks to the past and our heritage whilst looking forward to the future. We tried to create something which celebrates the book as whatever happens in the future this design is still going to be about books, even as we increasingly migrate to digital technology. You will see a lot of changes but the round reading room is a modern take on the British Library with practical functions and dramatic space to better display the collections.”

Rallying to her creations defence Houben added: “Libraries are the cathedrals of today; they are the most public buildings of our age. It’s public money developing people, it’s about knowledge. It’s not about books or analogue or digital, it’s about development and learning and creating space for everyone. From events in the book rotunda, to weddings in the Shakespeare room and musical performances on the terrace, it’s not just a library but a cultural hub.”

But wouldn’t Birmingham have been better off awarding such an important scheme to a home grown architect? Houben responded: “We have a very international team, we have 25 nationalities including people from the UK such as Patrick who lives in Birmingham - and people tell me he now speaks with a Birmingham accent, so he’s more British than the British!”

With the library now complete attention is turning toward John Madin’s concrete confection of 1974, now closed it is scheduled to be demolished next year, in tandem with a separate design competition for Centenary Square. The Library of Birmingham may be physically rooted in the city whose name it bears but as with the projects gestation the scheme’s ambition is without boundaries. It is the crowning achievement of recent regeneration work and marks a new chapter in civic works as well as being the last word in library design, rectifying the Shakespearean tragedy of post war urban planning for good measure.

|

|

Read next: Ice Lab

Read previous: Atria Edinburgh

Back to October 2013

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.