Changing Geography

22 Jul 2013

Yellow Book founder John Lord is at the forefront of research into the unprecedented demographic and social changes now sweeping Britain. Based on a lecture given at the Academy of Urbanism, the Changing Face of Everyday Life in Britain 1950-2010, the following text looks at the implications for our towns and cities.

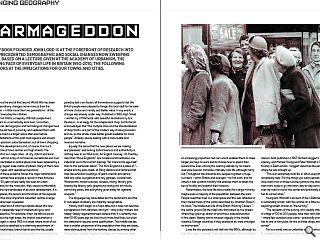

The period since the end of the Second World War has been a time of extraordinary changes, none more so than the transformation – in little more than two generations - of the geography of everyday life in Britain.Until the mid-1950s, a majority of British people lived what now seem to us remarkably local lives. Since then, economic, social, demographic and technological changes have fragmented the old ties of proximity and replaced them with lives which are lived in a larger space than ever before.

The manifestations of this post-local age are well known: rapid urban expansion, suburbanisation, out-of-town shopping, leisure and office developments and, of course, the much lamented decline of town centres and high streets. The hierarchy – within our major cities - of city, district and local centres, each with an array of commercial, recreational and civic amenities concentrated in central places has been replaced by a dispersed, city-region scale matrix of places, many of them new development types with specialised functions.

Faced with these powerful forces, the major national and regional city centres have enjoyed a revival in their fortunes in the past 15-20 years (there really has been an urban renaissance) and, for the most part, they coexist comfortably enough with the new landscape of exurban development. It is the middling places, the second and third tiers of the regional hierarchy and the once-important suburban centres in large cities, which have been squeezed.

The anguished and ill-informed debate about this new landscape is in desperate need of intellectual rigour and historical perspective. For example, when we talk (as we do endlessly) about the high street, the implicit assumption is that history began in about 1955 in a street where most of our daily needs could be satisfied by a charming assortment of independent local shops, branch banks and the like, usually within walking distance or a short bus ride from home. But this paradise lost is an illusion: all the evidence suggests that the British people were pleased to forego this local idyll for the sake of more choice and variety and better value. In any event, a change was already under way. Published in 1938, High Street – written by J M Richards with beautiful illustrations by Eric Ravilious – is an elegy for the independent shop, but Richards acknowledges that “the multiple store and the standardization of shop fronts…are part of the modern way of doing business and do, on the whole, make better goods available for more people”. Already we are dealing with a more subtle and nuanced narrative.

Equally, the sense that the new places we are making are “placeless” and lacking distinctiveness and authenticity is nothing new. In his 1934 book, An English Journey, J B Priestley describes “three Englands”: one timeless and traditional, one industrial, and a third which belongs “far more to the age itself than to this particular island”. This third England is a place of: “…arterial and by-pass roads, of filling stations and factories that look like exhibition buildings, of giant cinemas and dance-halls and cafes, bungalows and tiny garages, cocktail bars, Woolworths, motor-coaches, wireless, hiking, factory girls looking like factory girls, greyhound racing and dirt tracks, swimming pools, and everything given away for cigarette coupons.”

The language may have dated but the sentiments, and the ill-concealed snobbery, are instantly recognisable.

History didn’t begin on a fixed date and it does not describe a progression from darkness into light – only policy-makers and happy-clappy regenerationeers believe that. It is certainly true that 50-60 years ago we lived much more local lives, but even this statement requires some qualification. The middle classes, then a smaller proportion of the population than they are today, were distinguished from the working classes by, among other things, their mobility: they took holidays and weekends away, an increasing proportion had cars which enabled them to make longer journeys to work and to choose how to spend their leisure time. Even among the working classes, by no means everyone lived an immobile, intensely local life, although many did. Throughout the industrial era, people migrated in huge numbers – within Britain and overseas – to find work, and for others it was upward mobility that enabled them to break the ties of locality and expand their horizons.

Nevertheless, the local life was a reality for a large minority, maybe even a majority of the population, between the wars. People lived their lives in a small space and this was reflected in their mental maps of the world, described by Jonathan Rose in his book, The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes: “…the centre ground [of the map] was dominated by the streets where they grew up, drawn to enormous scale and etched in fine detail. Nearby towns hovered vaguely in the middle distance. Foreign countries, if they existed at all, were smudges on the horizon.”

Lives like this persisted until well into the 1950s, although by then they were in retreat. They were the subject of two modern classics, both published in 1957, Richard Hoggart’s The Uses of Literacy, and Michael Young and Peter Willmott’s Family and Kinship in East London. Hoggart describes the part of Leeds where he was brought up:

“This is an extremely local life, in which everything is remarkably near…For the things you want periodically you may drop down two or three hundred yards to the shops on the main tram route or go into town; day-to-day services are just over the road or round the corner, and practically every street has its corner-shop.”

Young and Willmott’s account of life in Bethnal Green is remarkably similar, with life centred on a little cluster of adjoining streets known as “the turning”:

“The residents of the turning, who usually make up a sort of village of 100 to 200 people, have their own places to meet – where few outsiders ever come – practically every turning has its one or two pubs, its two or three shops, and its bookie’s runner.”

This is a world now so unfamiliar as to be almost exotic, but it is important not to sentimentalise it. David Kynaston, whose history of post-war Britain is the outstanding account of the period, endorses the social historian Alison Ravetz’s view that “a more fruitful concept to apply to traditional working-class life than the ambiguous one of ‘community’ would be ‘localism’…it was the immediate locality that supplied the economy, the shared culture and the frameworks of personal development.” The contemporary record shows that, while the intimate scale of “the turnings” had its pleasures and consolations, many – perhaps a majority – were keen to escape both the often squalid housing and the stifling confinement of these villages in the city. Escape – from the gossip, intrusion, parochialism and narrow-mindedness of the locaility – was one of the defining themes of novels and films in this period.

So why did the change occur, and why did it happen so rapidly? This short article can offer only a partial account. The full story of the demise of the local life would show that it was already under threat in the pre-war years, and would reflect on the catalytic impact of the war, both on the physical fabric of our towns and cities and on social attitudes. In the post-war period, slum clearance and council house building erased and replaced many of the traditional bastions of localism. From the mid-1950s onwards, Commonwealth immigration brought ethnic diversity to places that had been a byword for uniformity. These are all vital elements of the story but there is not time to pursue them here.

The focus of my research has been on two key trends in the second half of the 20th century: the steady and almost uninterrupted increase in average household incomes and discretionary expenditure; and the rapid growth in car ownership and in distance travelled by car. Together, these trends created the conditions for unprecedented mobility and choice. A few key facts serve to make the point

real terms household expenditure increased by more than 2½ times between 1971 and 2007

in that period, growth in expenditure on essentials (food, drink, housing) was far outstripped by growth in the cost of travel and discretionary expenditure, for example, on clothing, household goods, leisure and culture there were just over 2 million private cars licensed in GB in 1951; in 2011 there were more than 27 million in 1952, the distance travelled by bus and coach comfortably exceeded the distance travelled by car, taxi or van; by 2011, the distance travelled by bus was less than half the 1952 figure, but the distance travelled by private vehicle had increased 11-fold, from 58 billion kilometres to 655 bn km.

The people displaced by slum clearance in East London contributed to the surge in distance travelled. In their new homes in Essex, they encountered a world in which “distances to shops, work and relatives are not walking distances any more. They are motoring distances: a car, like a telephone, can overcome geography and organise a more scattered life into a manageable whole”. Young and Willmott show how important these new tools were, not just as markers of modernity, but as a way of “clinging on to something of the old [life].”

It was the rising tide of prosperity that ended the idea of a local life and in the process sucked the vitality, and sense of purpose, out of town centres. As the journalist Ian Jack says, in an essay on his home town, Dunfermline, the declining fortunes of town centres wasn’t caused by the demise of traditional local industries like mining, shipbuilding and linen manufacturing: “What ended [the old way of life] wasn’t poverty but rootless wealth.”

If we scroll forward to the start of the new century, we can see how these driving forces have reshaped the landscape in and around our cities, creating a new geography of everyday life. With 12 cars for every 10 households we can live in a suburbanised “market town”, travel long distances to work (with the often overlooked benefit that, unlike previous generations, we can change jobs without moving house); drive our children to school; make major shopping trips by car once or twice a week; access an array of shopping, leisure and entertainment across the city region; and enjoy short breaks on the coast and in the countryside. This is what lives of “freedom” and “choice” look like – two more loaded terms that like “community” require closer examination.

There is any amount of empirical evidence that the majority of us have been willing participants in this social – and spatial – revolution. Equally, and despite the enduring appeal of a number of popular and attractive cities (including Edinburgh), attitude surveys show consistently that people living in smaller towns and the countryside are more contented.

Nevertheless, barring a huge increase in self-build or community development, someone has to present consumers with the new “choices”. This may take the form of tracts of new homes knocked out by the quite properly maligned volume house builders but, depressingly, this has been going on for a long time. More striking, because (J B Priestley notwithstanding) it is a real break with the past, has been the appearance of new building types like edge-of-town hypermarkets, retail parks, business and technology campuses and regional-scale shopping and leisure complexes. As these commercial developments have mushroomed, schools, sports complexes and the rest have also shifted to the edge, resulting in an accelerating centrifugal effect.

The impact on the urban form of Scotland has been captured vividly by Laura Hart, Joanna Hooi and others at the University of Strathclyde. Comparing maps from the 1950s and the 2000s we see a consistent pattern: population static or sometimes declining; a dramatic fall in population density; a huge increase in the footprint of settlements due primarily to suburban housing and edge-of-town developments; and the dispersal of civic and public buildings.

The effects of these profound changes are complex and by no means uniform. Edinburgh, for example, has not been immune to these trends but it continues to fly the flag for a model of high-density urban living, albeit one that only the relatively wealthy and privileged can enjoy. But as a general rule most Scots find themselves – willingly or not - in a situation whereby access to a car is essential for a full life. The inability (because of age, infirmity or poverty) to move freely around city regions by car has become a new form of deprivation. Conversely, struggling high streets are increasingly dependent on a captive market of people who are too old, too young or too poor to go somewhere better.

All this is daunting enough before we even consider the spatial impact of digital technology. In truth, it is too early to say what the potent combination of infinite content, infinite choice and transactions without physical presence will mean for places and spaces. Already we know that the relatively prosaic realms of gaming and cable TV have had a significant impact on the evening economy: we still like going out, but we do it less often. On the high street, thousands of bank and post office branches have closed because we can conduct transactions more conveniently online, and travel agents have failed because we can do for ourselves what they used to do for us. Among the retailers, bookshops and record shops have been hit particularly hard. Against a backdrop of recession and stagnation, online sales have continued to see double-digit growth. Social media have given a boost to the long-term trend to move away from communities of proximity and towards communities of interest.

Where all this will lead is unknown and unknowable, but I think it is reasonable to argue that, as in these past 50 years, the cities that are most attractive, prosperous and richly endowed with centres of learning, research and culture will continue to play a pivotal role in the life of the nation. Millions more people will want to live close to those cities, but not in them – in favoured suburbs and the accessible countryside. The real challenge will continue to be those less favoured places: former industrial towns and villages, the dreary backwaters scattered across the central belt, and the remote countryside.

As for the high streets – what politicians like to call “the beating heart” of our communities – many (but not all) of them are past saving, simply because they have no discernible purpose. This is sad, particularly for the now diminishing number of people who remember them in their distant heyday. It provokes a sense that, to quote Paul Fairley and Michael Symmons Roberts, “Over time we got what we wanted, and in the process we lost what we had”. But we must come to terms with it, and stop wasting time and money on fruitless efforts to revive the lifeless corpses. All this tedious hand-wringing has deflected us from the infinitely more interesting and productive task of making better places for modern lives.

Read next: National Review of Town Centres

Read previous: Liverpool Central Library

Back to July 2013

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.