Sunnyside Asylum

16 Jan 2013

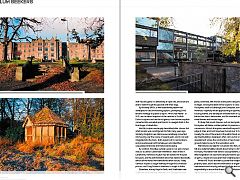

The decommissioning of Sunnyside Asylum by NHS Tayside marks the swansong for the oldest, and one of the largest, asylums in Britain. An architectural tour de force it now sits sadly neglected and prey to vandals. Here Mark Chalmers wanders its empty corridors.

Enoch Powell was a hellfire and brimstone orator, a politician of a different stripe to those who reach Parliament nowadays. Powell had moral convictions, and while he is remembered for the rhetoric of his ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech, arguably the ‘Water Tower’ speech he made in 1961 while Minister for Health changed more lives.Many associate the closure of asylums with the Thatcher government of the late 1980s, but the policy of Care in the Community was instigated by Powell. He identified, rightly or wrongly, that patients were being warehoused in mental hospitals, rather than receiving treatment. His ten year plan set out to de-institutionalise mental healthcare, proving perhaps that it takes a century for government policy to turn through a full 180 degrees.

Asylums for the insane, as they were known by the Victorians, emerged during an era when the term ‘institution’ had positive connotations. Yet their architecture seems at odds with that. Some asylums, such as Gartloch outside Glasgow, had dark brooding towers which cast a long shadow over patients and staff. Similarly, many Scottish asylums reached the scale of small towns: by the mid 1950’s, Hartwood in Lanarkshire was home to 2,500 patients, making it the largest in Europe.

It is telling that the emotive language Powell used in his speech evokes the architecture of the asylums, rather than the patientsí way of life, or their medical condition - “There they stand, isolated, majestic, imperious, brooded over by the gigantic water-tower and chimney combined, rising unmistakable and daunting out of the countryside - the asylums which our forefathers built with such immense solidity to express the notions of their day” yet that only tells part of the story.

The asylum was conceived as a nurturing environment, and operated as a self-contained community. Typically, accommodation for several hundred patients and just as many staff was provided on site. It was supported by laundries, kitchens, hairdressers, and a central boiler house which supplied district heating through a network of steam tunnels. Each asylum had its own sports ground, a recreation hall for sports and film screenings, and a farm which produced much of the food consumed there. Some, like Hartwood, even had their own railway station. Given that, a typical District Asylum seems like a good model for sustainable living.

However, Powell’s belief was that the services themselves should form the identity of mental healthcare, rather than the buildings, and as such, the buildings had to be dismantled. That process has taken half a century, but now most of the former asylums in Scotland have closed, to be replaced by Care in the Community, often delivered through smaller psychiatric units co-located within general hospitals.

Arguably Powell’s speech is only one step along a journey of reducing institutions into smaller units: the Edwardians had already concluded that the ‘pavillion’ or ‘colony’ plan, which split a single huge echelon-plan building into smaller ward blocks, was more sympathetic to the patients.

By the 1960s, psychiatric units had further reduced in scale, and perhaps the best Modernist example is Peter Womersleyís Herdmanflat Hospital in Haddington. Its low, glassy horizontality owes more to the Case Study houses of the Pacific coast then the towers of Gartloch, and the forbidding ‘asylum wall’ has also gone: it is effectively an open site, and locals are able to walk through the grounds with their dogs.

By the early 1990’s, a well-established pattern had developed for decommisioning asylums, prompting SAVE Britain’s Heritage to publish a report, ‘Mind Over Matter’. In 2012, we can take a snapshot of the network of Scottish District Asylums and see the full gamut, from former hospitals converted into upmarket apartments, to ravaged shells in the final stages of dereliction.

Murthly Asylum was largely demolished after closure, but what remains was reconfigured into flats many years ago. Similarly, Dingleton near Melrose was sensitively converted into housing over the course of several years, and is now well integrated into the town. Both asylums sit in rural locations, and proved popular with homebuyers who liked their sequestered character and mature landscaping.

By contrast, Woodilee outside Lenzie is now just a ruined shell, as is Lennox Castle near Kirkintilloch. Near Shotts in Lanarkshire, Hartwood Asylum has lain derelict for the past few years, and the administration block has deteriorated badly: almost all the wards were demolished after closure. Today Gartloch Asylum is caught halfway through the conversion process, and Craig Dunain in Inverness is caught in limbo.

Elsewhere, Murray Royal in Perth, and Stratheden near Cupar are still active sites whereas Liff in Dundee has been partly converted, with the last active parts being shut down in stages. Among the latest former asylums to close are Rosslynlee, south of Edinburgh, and Sunnyside, outside Montrose. Hopefully we are approaching an upswing in the housing market, and developers will take them on quickly, before their fabric deteriorates, and the inevitable attacks from metal thieves and vandals begin.

It’s likely that recent closures, such as Sunnyside or Rosslynlee, will follow a similar pattern to previous successful conversions. Almost all asylums were built beyond the edge of cities, and most have been turned over to housing. Usually, the core of the asylum is the admin block, and many are listed buildings: developers often carry out an ‘enabling development’ where the construction of new housing in the grounds helps to pay for the restoration work.

Ward blocks are ideal for conversion into flats, although folk are understandably reticent about living in a former mortuary. Recreation halls tend to cause problems, although a little imagination can see them being turned into sports clubs or gyms, a logical end use given their original purpose.

While NHS Trusts are keen to pocket the receipts of property sales, and to absolve themselves of ongoing maintenance and security, perhaps the State also has a responsibility to ensure that these unique institutions aren’t wiped from our collective mind.

Read next: Kendram House

Read previous: George Square survey

Back to January 2013

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.