Kericho Cathedral

24 Apr 2012

Scots missionaries may no longer be spreading the good word in Africa but now one Scots architect has been handed the opportunity to design a building type which has all but disappeared from Britain - a brand new cathedral. Here Peter McLaughlin of John McAslan + Partners explains how a community 7000 miles away had faith in him to build their majestic new cathedral.

The inception of the cathedral for the diocese of Kericho in Kenya was driven by the aspiration to provide a cathedral that was beautiful, inspiring and of lasting quality, but that was also functional. The architectural challenge was to ensure the cathedral embodied the Catholic liturgy and embraced its local congregation in a way that reflected both the historic gravitas of the faith and the special qualities of its location and its community - a response which must make the cathedral both unique, and yet universally welcoming.

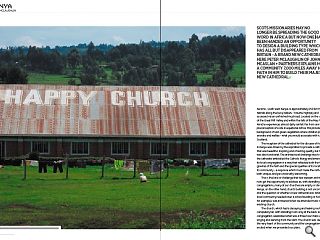

This is the kind of challenge that few western architects now get the opportunity to address as, with dwindling congregations, many of our churches are empty or derelict. In Kenya, on the other hand, church building is not uncommon and the question of whether a new cathedral was what the local community needed (over a school building or hospital for example), was answered when we attended mass in the existing church.

The church, which had a decaying and leaking roof, was completely full, with standing room only at the back, and the congregation celebrated what was a three hour mass with singing and dancing from the start. The church was clearly the very heart of the community and the congregation were excited when we presented our plans.

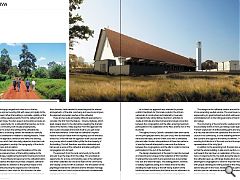

The site enjoys magnificent views across the tea plantations and surrounding hills with views principally to the north and east. When the building is complete, visibility of the cathedral will be equally powerful from the valley itself and the adjacent ridge. The site’s aspect and location provides an incredible opportunity for a cathedral that reaches out to its extended community, both visually and physically.

In order to ensure the setting of the cathedral was appropriate to its existing context we needed to carefully consider its orientation in relation to existing features. These included the approach, entrance and views; the existing Emityot tree, which has historically played an important role in the congregation’s worship; the topography of the site its setting access and circulation.

Of particular importance was the balance of the site, notably the scale and mass of the building relative to the open landscape, neighbouring domestic housing and school buildings. The architectural response for the cathedral had to carefully balance the desire to provide a majestic cathedral which celebrates its devotion to the spiritual needs of the Diocese while ensuring the response was not boastful. Bishop Okombo’s clear vision for the cathedral, the altar and the congregation as a wider expression of the family at their domestic table needed to extend beyond the internal arrangements of the altar, sanctuary and nave to encompass the approach and wider reaches of the cathedral.

There are two quite principally different approaches to consider; the first from the Nakuru – Kisumu Highway, which leads steeply down to the site before revealing the dramatic views of the Kericho Valley beyond. From this approach the site is quite concealed and reveals itself as you get closer to the main entrance. Given that the cathedral’s highest reaches would be visible from the highway but the entrance would not, it was felt that the approach itself could be seen as a journey which reveals little by little the true majesty of the building. This fall, therefore, would be celebrated and harnessed, a sense of the cathedral, and altar, pulling the congregation into its heart.

The approach from the rural community to the north and east is up the slope from the valley. This provided an opportunity for a more commanding view of the cathedral – one which celebrates its role at the heart of the community and visually connects with its outreach. The articulation of the pilgrimage towards the cathedral and the timeless marriage between land and church produced the most fundamentally engaging quality of the design.

At its heart our approach was intended to provide a distinct landmark for the locale rooted in the African vernacular of construction and materiality. It was also intended to fully satisfy Bishop Okombo’s ambition to create an intimate and direct physical and visual connection between the congregation and the altar, ensuring maximum participation in the celebration of the Mass and the Act of The Eucharist.

Throughout history Catholic cathedrals have been based on two principle plan forms; the Latin cross, with its extended nave and transepts, and the Greek cross with a centralised plan and altar. Modern interpretations of these two patterns of worship have all attempted to overcome the distance between the congregations and the altar in order to improve participation in the Act of the Eucharist.

The design development of the plan for Kericho involved an interesting and unique further adaption of this transition. It retained the nave with its processional axis and provides two east and west transepts. The seating pattern, however, is radially organised, being at its widest around the altar, avoiding the right facing or the left facing dualism of the traditional plan and allowing the Bishop and his attendants to speak directly and intimately to the entire congregation.

The design for the cathedral centres around the formation of one ascending vaulted volume. This enormous room is expressed by its great inclined roof which will become an unmistakable form in the rolling panorama of Kericho’s hills and valleys.

The structuring of the roof and its vaulted construction are essentially Gothic in form, providing a clear legible, and “honest” expression of all the building parts and organisation. In a very real sense the roof symbolises the role of the church in the community, it is the sheltering environment that sustains and supports the family of believers. The resulting bird-like form of the main roof and transepts is also representative of the Holy Spirit

In addition to the ascending roof, the plan also splays so that the whole building, in plan and in section, is opening out towards the Sanctuary in celebration of the service of mass. In response to this, the walls along the side aisles of the cathedral open up, with large double doors on every bay, allowing the congregation to swell for important feast days, with people standing and sitting outside in the wings being able to take part in the mass. Allowing for this permeability will also give the cathedral an openness and airiness that will make it feel truly African.

The doors need not always be open and there is strong symbolism in the idea of these doors being thrown open after mass, allowing the light to pour in and for the congregation to flood out in all directions to spread the good news.

In line with the great tradition of ecclesiastical architecture, the primary structure of the building is expressed internally as a series of parallel concrete arches that increase in height and span towards the Sanctuary, picking up the ascending roof structure and the splayed plan.

The mass and solidity of the concrete is offset by a delicate veil of timber battens that span between the arches, adding warmth and texture to the internal palette of materials. The large planes that form the roof over the central nave of the cathedral will be finished in traditional tiles made in Nairobi from Kenyan clay. To give these large roof planes a character and texture some of these tiles will be cut and arranged in a pattern that will give an abstract reference to wheat. The design of this pattern is being progressed by John McAslan + Partners in collaboration with the artist John Clark.

The theological significance of wheat is considerable, from the direct association with the bread wine and, therefore, the Holy Eucharist, to the regular references to wheat in the Old Testament as symbol of God’s bounty and hence of thanksgiving.

Rendered stone provides a strong and robust base; the clean lines reinforce the strong geometry of the cathedral and express the qualitative nature of the building. It also grounds the cathedral within the landscape. Internally the vaulted interior is then framed with the striking concrete ribs and a clean rendered stone interior. The great roof sweeps down, cantilevering out over the external walls to enable circulation externally in the frequent rains. The thermal mass of the stone base, the double skin roof and the continuous central rooflight work to passively manage the climate; naturally cooling and ventilating the cathedral.

Simplicity, warmth, solidity and permanence, balanced with a commitment to the integration of local materials, were the ambitions for the material palette and the use of local materials and labour will ensure a truly sustainable development. As Kenya’s own Professor Wangari Maathai noted ‘we must transfer knowledge and skills on the sustainable use of natural resources from the laboratories to the villages and rural communities and, in doing so, improve people’s lives and the culture of peace’.

John McAslan + Partners are working with Arup and a form of architects in Nairobi called Triad, who will be responsible for monitoring the development of the works on site. Their advice into local buildability issues and supply chain has been invaluable and it would not be possible to design and construct a building in a remote site in western Kenya without such skilled and knowledgeable local partners.

Works started on site in February 2012 and are anticipated to continue until August 2013.

|

|

Read next: Top Landscape Architects

Read previous: Awards or Rewards?

Back to April 2012

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.