Glen Fruin

24 Apr 2012

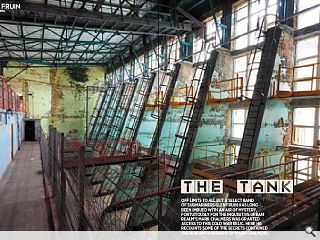

Off limits to all but a select band of submariners Glen Fruin has long been imbued with an air of mystery. Fortuitously for the inquisitive Urban Realm's Mark Chalmers was granted access to this cold war relic. Here he recounts some of the secrets contained therein.

“War science”, as Winston Churchill called it, was crucial to the conduct of World War Two and was led by men like the Nobel laureate Patrick Blackett, and Frederick Lindemann, who Churchill called “the scientific lobe of my brain”. Blackett worked with Coastal Command to develop tactics for hunting U-boats. Each operation was broken down into a series of discrete events, then the statisical advantages of incremental improvements were evaluated. Blackett’s approach gave rise to a new science, operational research, and before long the new tactics convinced the Kriegsmarine that Britain had developed a radical new weapon.

The torpedo was invented by Robert Whitehead in the 1860’s, and during the First World War, experiments on dropping torpedoes from aircraft were carried out by the Fleet Air Arm at Gosport. The Admiralty had a testing facility in Portsmouth, and it became the Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment when World War Two broke out. Operational research ensured that existing technology – such as the air-dropped torpedo – was used more effectively, and after war was declared the establishment moved from the south coast of England to the Helensburgh area.

Reputed to be the largest of its kind in the world, the torpedo testing tank at Glen Fruin was built in 1940 to study anti-submarine weapons, and sits on a hillside above Garelochhead. Ironically, the torpedo was made famous in 1942 and 1943 by attacks against German battleships: Churchill’s order to disable the Tirpitz was carried out by Barracuda aircraft; her sister ship the Bismarck was crippled by primitive-looking but deadly Swordfish aircraft launched from the Ark Royal. Work at The Tank helped the torpedo’s designers to understand the split-second when it broke the surface: that impact, and how it affected the projectile’s course, wasn’t well understood at the time.

The Tank is a piece of engineering from the heroic era of Barnes Wallis, Reginald Mitchell and Frank Whittle: its massive buttresses loom over an army camp consisting of sangars, Quonset huts and support buildings. In fact, the wider area is a military landscape – HMNB Clyde and its facilities for Trident submarines, which are coldly impressive in the way that the ramparts on Edinburgh Rock must have seemed to our ancestors. Along with the tank at Glen Fruin, a range was built nearby at Loch Goil, and a giant launcher at Coulport.

The Tank measures around 50 metres long, 10 metres wide and 15 metres deep, and is built primarily from concrete. Scottish engineers developed a particular aptitude for structural mass concrete work – pioneered by McAlpines on the West Highland Railway extension in 1890’s, and developed through hydro-electric schemes such as Laggan and Tummel in the 1920’s and 30’s. It is to dam engineering which the Tank at Glen Fruin most closely relates – a 13-bay gravity buttress structure which resists the outward thrust of almost one million litres of water.

Inside, the large observation hall is roofed, but the tank itself is open to the sky, presumably to allow as much light as possible in for the high-speed cameras – given the relatively slow films of the 1940’s. The galleries in the observation hall, onto which the cameras were mounted, span between the buttresses. The resulting space has the dramatic scale of a deep sea aquarium, and the buttresses become an elegant way to articulate the structure. The 30mm-thick armourplate glazing has a green cast which must have been magnified when the tank was brimmed with water. The panes were bolted into a steel frame using steel glazing bars, compressing a layer of “Bostik” sealant.

Outside, a control room on the roof took command of the tank, which is oversailed by a pair of box girder gantries and two catapults which launched projectiles using compressed air. Originally, a 30 metre long runway accelerated them up to a speed of 300mph: according to the Defence of Britain Project, Glen Fruin was used to test scale models of torpedoes, depth charges and mortars. The bank of accommodation to the south of the tank housed machine shops to build the test models, darkrooms to develop the photos, and labs to study the instrumented results.

The tank’s genesis lay in modern technology: an understanding of hydrostatic loads, the development of toughened glass and sealant glazing, and progress in concrete buttress structures. In parallel came improved instrumentation, such as high speed cameras and accelerometers, and eventually digital computers. Anecdotally, the catapult technology was derived from that used aboard aircraft carriers, and Scottish firms such as Brown Brothers of Edinburgh and Mactaggart Scott of Loanhead are still world leaders in that field.

At the time, much of Glen Fruin’s work was secret, and it continued in use through the 1980’s, helping to develop today’s weapons. Yet the research also saved lives. Carrier-borne aircraft such as the de Havilland Sea Vixen were difficult to escape from if ditched in the sea: 1960’s tests at Glen Fruin proved that ejection seats could be fired underwater, propelling the crew to the surface. Later, an entire Lynx helicopter was dunked in the tank to ensure the crew could escape.

The Tank is a unique structure, in the same way that the pagoda-shaped laboratories on Orford Ness where nuclear bomb triggers were tested, the enormous rocket launch pads at Spadeadam, or the gas turbine altitude cells at Pyestock in Hampshire, are one-offs. Each was built to follow a very specific line of scientific inquiry. The tank was used less frequently after the advent of computer modelling – ironically, since the empirical data gathered during tests at Glen Fruin helped to design the algorithms which the virtual models rely on – and in 1986, Glen Fruin was converted into a density-stratified tank to carry out a different type of research.

Just as its role evolved over time, the tank’s name changed, too. After the war, the Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment became the Admiralty Hydro-Ballistic Research Establishment, then the Admiralty Marine Technology Laboratory, and latterly it was a part of Qinetiq, the privatised defence technology firm. Today the tank, now a listed building, is part of the Defence Training Estate and is used to train soldiers to fight in built-up areas.

|

|

Read next: The Works

Read previous: Spring Manifesto

Back to April 2012

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.