Nairn review

13 Jan 2012

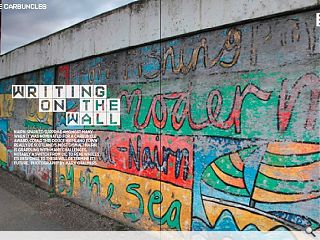

Nairn sparked surprise amongst many when it was nominated for a Carbuncle award. Could this douce Highland town really be Scotland's most dismal? Nairn is grappling with many challenges, notably a switch from oil to renewables. Its response to these will determine its future.

Mark Chalmers: Senior Project Officer, SustransOver the past decade or so, the Carbuncles have captured the popular imagination. Community activists quickly grasped that publicity in the anti-awards gave them leverage – and for that reason, politicians resent them. Folk don’t like their deficiencies being pointed out, and which town or city couldn’t bear some improvement?

Yet perhaps a more apt question is where you set the Carbuncle baseline. It’s the same judgement which the Scottish Government makes when regeneration takes place in areas which score highly on their “index of multiple deprivations”. Not everyone agrees with using that yardstick, though, and the key issue is egalitarian – to each according to need, or fair shares for all? As a result, some of this year’s nominations come from towns like Nairn, a douce Royal Burgh on the “Scottish Riviera”. It doesn’t seem like natural Carbuncle material, so we went to investigate.

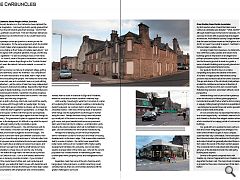

Nairn’s economy is a mixture of retirement village, golfing resort and dormitory suburb for Inverness – but compared to the out-of-town retail deserts of the latter, Nairn’s High Street is affluent and bustling with people. We visited the Inshes area of Inverness last year and concluded it was a car park with big sheds attached – yet the centre of Nairn has many independent shops housed in characterful buildings. Beyond the High Street lie a couple of derelict buildings, one of which is scaffolded, and an abandoned petrol station. Dereliction should be accepted, grudgingly, because we know towns have to evolve – the issue is its extent, and how long it lingers for.

Nairn is split by the busy A96 trunk road, and it has exactly the same issue with through traffic as nearby Elgin. Its many sets of traffic lights are an irritation to drivers, yet the crossings help to stitch the town together for pedestrians. As in Elgin, the need for a by-pass conflicts with the hope for passing trade; the development of the town fights against the flow through its main artery. The government’s plans to upgrade the trunk road are there, in the background: it’s difficult to say what the impact will be although nearby Huntly is probably a guide.

Nairn consists of three parts – the old fishertown with its couthy little streets; a Victorian core with grand tenements and hotels; and modern bungalows around the edges. The approaches to the town have quite different characters: from the west you travel through a landscape of Victorian villas, from the east you pass some industrial units and a new supermarket. The latter seems like a grudging concession to progress, and one comment we heard was that the small Sainsbury’s store was preferable to a huge Tesco, as was the case in Huntly.

As we walked through Nairn, we were struck by the lack of typical Carbuncle cues - such as sink estates, abandoned factories or decaying concrete monsters. If you consider it against the coastal towns further east, such as Buckie and Fraserburgh, you realise that Nairn’s issues with dereliction and traffic are transient, whereas the fishing ports have deep-seated structural problems with employment and communications. Instead, Nairn is closer in character to Elgin and Fochabers, where the social and economic baseline is relatively high.

Until recently, Fraserburgh’s waterfront consisted of a series of mouldering fish factories; Buckie’s coastline is dominated by derelict boatyards. By contrast, Nairn’s small harbour is now a tidy little marina – with none of the fog-bank of dereliction which hangs over the dying North Sea fishing ports further along the coast. Perhaps because fishing historically made up a small part of the town’s economy – its championship golf course, and grand seaside hotels are more prominent – Nairn was hit less hard by its collapse. Local fabrication yards, including the site at Ardersier which sat in mothballs for many years, are now earmarked for wind turbine manufacturing.

Perhaps the underlying concern which prompted the town’s nomination is a fear for the future: the threat of housing developments on the town’s edge. That unease often manifests itself in a series of ciphers – the call for lower speed limits really means cutting out non-resident traffic; higher quality development translates into exclusivity; and conservation equates to preservation of the status quo. After all, the current population has a vested interest in maintaining quiet roads, uninterrupted views, property prices and manageable school rolls.

Regardless, Nairn has none of the anti-charisma which hangs about Carbuncle towns, so whilst some things could certainly improve, there are communities elsewhere with far greater challenges to surmount.

Drew Mackie: Drew Mackie Associates

My first reaction when I heard that Nairn was a Carbuncle candidate was disbelief - “what, NAIRN?” although I hadn’t been to the town for decades, I had a picture of a town with a seaside feel and elegant architecture. And indeed a cursory Google revealed that the town had been known as the Brighton of the North. So I wasn’t sure what to expect - had Nairn’s fortunes taken a sudden dive

Arriving in Nairn from Inverness, my initial picture was confirmed. Leafy suburbs and robust stone buildings gave an impression of an elegant and perhaps prosperous place. However, as we turned into the Museum grounds to meet our guide, a series of derelict buildings and a poorly placed and designed supermarket hinted at worse.

Our guide for the first hour or so told a compelling story about the decline of the town. A number of inappropriate interventions at key junctions had started to eat at the town’s character. The ups and downs of the oil industry had perhaps eroded the confidence and sense of direction of the place. And the loss of its own Council meant that planning decisions were taken without a local perspective.

However things took a turn for the mysterious when he refused to be filmed, photographed or recorded and wouldn’t tell us what he did or a living. A vaguely military bearing hinted at an expatriate life - we fantasised a special forces wet works specialist with a ceramic knife at his ankle.

On our car borne tour, he described the harbour as a missed opportunity - as indeed it seemed to be - and showed us the less than elegant eastern entrance which consisted of a scrappy jumble of commercial buildings.

Our guide left us to explore the town centre on foot and a more intriguing picture emerged. The town centre of Nairn is a gem. It has a compact scale that feels very comfortable. There have been a few intrusive modern interventions but the rhythm and scale of street has generally absorbed these. In fact scale is the secret of the town centre’s appeal. The occasional narrow side street adds interesting glimpses of the backlands and an the odd quirky building adds surprise.

Several of the panel compared Nairn with Peebles. By chance I happened to be in Peebles a few days after the Nairn visit. The main street in Peebles is grander but has a less cohesive feel. I think Nairn is better!

Read next: Winter Manifesto

Read previous: Carbuncles 2012: Linwood

Back to January 2012

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.