Corb your enthusiasm

14 Jan 2010

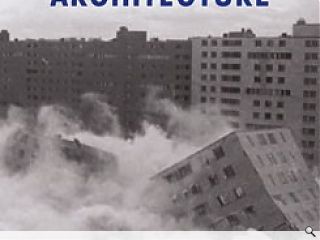

He is a figure from the past who embodies the modern and continues to hold architects in his thrall. But is modernism a failed architectural dead end? Or the bedrock upon which we need to base solutions to today's needs? In his new book 'Exploding the Myths of Modern Architecture,' Malcolm Millais advances the former prognosis.

Corbusier, dubbed "Corbuncle" by Millais, remains something of a leviathan in architectural circles by squaring up to prevailing orthodoxy with new geometrised forms, instigating and promoting many of the features that came to define modernism.A pioneer of the architects' "persona", where specific fashion and accessories were harnessed to cultivate fame and a sense of importance through image, beginning with the carefully chosen title of Le Corbusier as Millais describes: "It allowed him with the 'Le' and no first name, to become something objective like a 'historical phenomena' or 'object type'" but also to: "write about himself in the third person". This was accentuated by the acquisition of heavy black framed, round glasses, a dark suit, bowler hat and bow tie. This need to devise a persona is pursued to this day by architects such as Jean Nouvel, who dresses entirely in black save for when on holiday when he chooses to dress in white, or indeed the (in)famous red trousers' of former RIBA president George Ferguson.

A further plank in the Corbusier ideology was to disassociate architecture from historical styles, with Corbusier arguing in the modernist bible "Vers une architecture" of 1923 that "the styles are a lie", seeking with revolutionary zeal to embrace modern technology in the pursuit of "machines for living in".

Millais alleges that Corbusier's work was driven by a desire to "satisfy the architect rather than the client" and provides a list of design flaws evidenced at Citrohan House. Inspired by Henry Ford's innovations in assembly line production and the white washed flat roofed houses of the Greek islands which had impressed Corbusier on earlier travels, this home was built around a reinforced concrete frame with flat roofs, everything rectilinear and without decoration.

Despite an avowed aim of modernism to aspire toward the 'functional' Millais points out that many of its tenets are fundamentally non-functional. Singling out flat roofs as being ill suited to temperate climates, double height living spaces as inefficient in energy consumption and usability, curtain wall glazing which gave rise to an internalised greenhouse effect and flush external walls that were predisposed toward staining and leaks.

Millais blasts: "Le Corbusier never had even a minimal grasp of the basic laws of physics that determine the technical performance of buildings heat transmission, load carrying systems, sound insulation, acoustics, the effect of natural and artificial light or the technical performance of construction materials". Proclaiming his work as rational and scientific he in fact floundered by ignoring the key tenet of science accepting and rejecting theorems on the basis of experimental results ditched in favour of preconceived ideas.

Undaunted by such travails Corbusier went on to draft perhaps his most famous work, a city of three million people arranged in stacks of cruciform plan Citrohan houses. This served to elevate Corbusier to the architect of entire cities and was to become an important spur for the megalomaniacal plans of post war reconstruction effort as a template for urban design. Taken to its extremes this approach led to 1926's Plan Voisin which called for the complete rebuilding of Paris with streets aligned on a rectangular grid dominated by cruciform skyscrapers. Replicated endlessly for anyone in any location the sterile spaces found little favour with the public, a dichotomy that has persisted to this day.

Also published this year was Corbusier's Five Points of a New Architecture where the architect sought to isolate succinct steps toward the ideal building by outlining critical steps which included: lifting buildings up on columns to free ground level areas for other uses, non load bearing internal and external walls to allow flexibility of space and curtain wall glazing, windows aligned in long strips and roof terraces that replicate the building footprint.

Considered the apogee of cubical white houses, Corbusier's Villa Savoye of 1928 suffered numerous technical flaws including cracks, stains, leaks and condensation. Over budget, the project proved so problematic that the family who commissioned it rarely used it, eventually finding use as a hay barn by local farmers. Perhaps unsurprisingly for a family home from a man who was vehemently anti-family, the architect was quoted as saying: "I hate children, they are the curse of society. They make noise, they are messy and should be abolished".

Millais fires: "The lauding of Villa Savoye, in numerous books and by numerous Modern Movement architects, encapsulates beautifully the basic deceit of the Modern Movement. Here is a building that is supposed to be a house, a role it was never able to fulfil, later promoted endlessly as one of the high points of Modern Movement house design."

Interestingly, many early Modern Movement sites, such as Quartier Fruges, an estate of workers housing near Bordeaux, are now privately owned and have been subject to alterations by their owners to make the properties more individualistic. Numerous additions of pitched roofs, porches, shutters and reductions to the size and shape of windows have been made, to the horror of architectural purists, many of them architects, who have restored several properties to their original appearance.

Having cast a pall of doubt over Corbusier's architectural credentials, Millai goes on to call into question his ethics, specifically a murky period spent in the French Vichy government as chief of the state housing organisation. He was subsequently fired.

Nevertheless, war-damaged Europe provided the perfect cloth for this new no-frills design with Corbusier famously developing his Modulor Man at this time, a dimensioning system that attempted to bestow numerical relationships to buildings that would resonate with an underlying mathematical beauty. Curiously, this dropped the metric system in favour of a system of measurement predicated upon a relationship between the Golden Section (a ratio), the Fibonacci sequence (a numerical pattern) and the human body.

Allegedly any building constructed to these dimensions would comply with a human version of the divine proportion but in practice made little sense in a species of diverse size and shape.

Unite d'Habitation was the first of Corbusier's schemes to embody Modulor Man (though not fully) and has come to be regarded as his crowning achievement. Designed for the French Ministry of Reconstruction in 1946, Unite was a huge structure occupying a plot of 165 by 24m and rising to 56m in height. Following both the five points and modulor proportions, an innovative construction method of constructing a frame of "beton brut" concrete (concrete poured into timber formwork) within which prefabricated housing modules could be slotted proved too ambitious for realities on the ground. Instead each unit, together with their external walls, was prefabricated on site.

Interestingly this specific form of concrete devised by Corbusier ultimately gave rise to the term brutalism, referencing the material itself and not the raw appearance of the buildings in which it was employed.

Corbusier, in pioneering all-glass facades, came to invent the sunshade, or brises soleil, which prevented the suns rays from penetrating when the sun is high in the sky but not when low to the ground and were installed on south facing facades. Difficult to access high up on the facades these quickly became a magnet for dirt and grime. In any event the main facades of Unite face east and west, leaving residents exposed to solar rays regardless.

The sculptural quality of these inserts together with an assortment of brightly painted balconies did however create an infinite variety of splayed light. These qualities were not always reflected internally though, where several bathrooms and children's bedrooms were left with no natural light thanks to a rectangular floor plan that created tunnel like spaces.

Curiously Corbusier went on from this ultimate distillation of modernism to design an altogether more organic form for a chapel at Ronchamp in 1955. Sporting a grotto like interior and small windows glazed with coloured glass, this approach threw Corbusier's own rulebook out the window to embrace irrationality.

Corbusier's largest project was undertaken in India, the state capital of the Punjab at Chandigrah, completed in 1955. Built on a grid the city evidenced both rational and irrational elements with heavy use of sculpted beton brut built around a basic rectangular pattern. Criticisms were levied at the city for imposing western solutions to Indian problems. In homes this saw rooms reconfigured to suit the occupants, windows papered over for privacy, and food cooked on the floor rather than worktops. Millais adds: "The shopping areas did not suit the Indian way of shopping, essentially a bargaining process which required a number of similar shops in the same area, the opposite of what was provided."

From early in his career with the Quartier Fruges fiasco, through almost every project up to his Indian swan song, Corbusier's built projects repeatedly exhibited a whole gamut of failures. Budget overruns were endemic, environmental problems normal, maintenance often problematic, and quite frequently the end users were unhappy.

Moreover, Millais contends that: "almost nothing Corbusier did was original: white cube houses had been built before, reinforced concrete construction was well established. Le Corbusier's approach to building design was dishonest and uncaring. He promoted the idea that he was pursuing research into how buildings could be functional, but he did no real research." Millais concludes: "No-one, at least in the architectural community, seems to be able to draw the obvious conclusions, perhaps it would be too damaging. Too damaging to admit that, like modern art, modern architecture is not intended for ordinary people."

Perhaps the real failing is less of Corbusier's doing and more his successor's in elevating the status of one man's work beyond reason and, in so doing, failing to remedy inherent design flaws, flaws that came to be replicated in thousands of developments across the world decades after they had first been identified.

The Last Word: Malcolm Millais

One of the greatest deceptions played on the developed, and developing world, starting in the 1950s, is modern architecture. Everyone knows what it is, it is all those ugly, sterile, inhuman buildings that have been built all over the planet Ð 'the ugliness that spreads like gangrene' as one non-architectural writer put it, or 'the dreadful modern industrial city, like a pile of discarded shoeboxes' as another saw it.

How did this disaster happen? It happened because the global architectural profession fell into the clutches of a group who thought architecture should be based on modernism Ð hence modern architecture. Modernism was the reaction of a small group of disaffected intellectuals to industrial progress. They felt it was producing a world that caused alienation and despair in sensitive individuals, and art should reflect this. When this art, called modernism, was applied to architecture, it produced buildings with no joy, charm, physical or emotional comfort. The doyen of this approach was Le Corbusier, who thought a house should not be a home but a machine. He had his houses photographed as he saw them, as 'empty luminous spaces, removed from the contamination of domesticity' as architectural writer Kenneth Frampton put it.

In writing 'Exploding the Myths of Modern Architecture' I wanted to reveal how modern architects had based their approach on a complete misunderstanding of human needs. Even worse, whilst proclaiming that their buildings were functional, they failed to understand even the most basic building technology. When this became all too obvious, instead of abandoning modernism, they turned it into a cult and themselves into an arcane sect. Safely swaddled in their weird beliefs like 'form follows function', 'less is more' or 'ornament is a crime', they carry on, happily oblivious to the protesting cries of the rest of mankind.

|

|

Read next: Howden Park

Read previous: Dereliction of duty

Back to January 2010

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.