John McAslan looks at Glasgow Waterfront

24 Jun 2008

Fudging on the dock of the bay Throwing money and a grand idea at a ruined dockland is not enough to regenerate the Glasgow waterfront. John McAslan has a primal fascination for industrial architecture, and argues that good leadership is needed to harness the latent energy that is found in these landscapes.

THE pursuit of architecture in Britain in the 21st century is often enervating, and sometimes almost shockingly satisfying. Submissions, competitions, invitations, fee wrangles, project cancellations and commissions form the sedimentary layers of the professional coalface at which all but the most supremely privileged architects must work. If we consider a particular seam in that coalface - Scottish waterfront development schemes - the word enervation is barely adequate. In some of these schemes, there is little or no architectural, urban or public realm quality. They suggest a sugar-rush brashness, designed to suck people into new, dislocated milieus whose character is predicated on size and graphic effect, rather than diverse human and urban energies.

The quest for architectural and placemaking quality in these projects is not only a question of applying design skill, or of the architects' obdurate determination to communicate ambitious ideas. The meltdown starts before that. The quality of architecture and place - and therefore peoples' lives - will inevitably suffer if these massively important developments lack a visionary leadership that begins with the boldest decision of all: to base a masterplan on thoroughly thought out infrastructure and public realm interventions; and on appropriate variations of newly created urban densities.

Without this primary template, and the necessary spending commitment, all that will be produced are the viral 'deliverables' of mediocre schemes that will infect or destroy architectural design processes in these waterside contexts. There is no reason to pursue new waterfront development schemes unless they create new urban connections and spaces that work. Is there something to fight for on the urban edges of Scottish estuaries, or not? I think there is.

Architecture, at any scale, is a journey made by both architect and client to a dynamic point of either ambitious understanding and fruition, or craven compromise. Too many schemes on Scotland's key waterfronts - most obviously at Leith and Glasgow Waterfront - fall into the second category. There is a poverty of architectural and place-making ambition. Where is the sustained public complaint about dire schemes? Where are the Exocet questions about strategic investment in infrastructure, and ambitious project leadership? I'll return to these issues in a moment.

The majority of architects involved in these schemes are certainly talented; some are extremely talented. I know this not just from studying schemes by Scottish studios in, say, AJ or BD, but from first-hand experience. In setting up a competition to design a new building at Dollar Academy, I was in absolutely no doubt that the shortlisted Scottish practices were quite excellent. Ultimately, we selected Page and Park, but we knew from the other interviews and presentations that all the competing practices were capable of delivering equally engrossing architecture.

Why is it that, despite the obvious quality of many Scottish practices, and the proselytizing work of organisations such as the RIAS, ADS and the Lighthouse, that the architectural world exhibits a relatively massive interest in the Irish architectural scene, which is perceived as a 21st century architectural hotbed as influential as Switzerland or Spain were in the two decades up to the millennium? Is there something significantly different about the commissioning climate there? Is this why NORD, for example, had to go to Ireland to win their first really big civic commission? Why wasn't their first major scheme in Scotland?

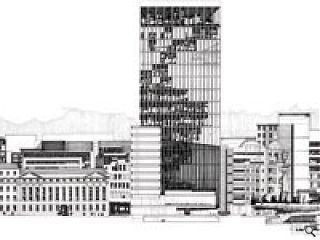

The talent of Scottish practices of this calibre is always in danger of being lost in the quicksands of the more unfortunate waterfront schemes at Glasgow and Leith. The "isolated stupor of the object" spoken of by the brilliant Spanish architectural critic, Ignasi de Sola-Morales, reminds us that meaningful architecture in regenerative contexts must address a great deal more than site boundaries, main facades, skylines, or value-engineered profitability. Has the "iconic" architecture plugged into Glasgow Waterfront lessened the sense of a tundra on the banks of the Clyde? There is no engaging physical or human relationship between this scheme and the city.

In Edinburgh, the Waterfront City scheme has an eminent design champion, and a well-respected design leader whose ideas are often perceived as inimicable to the local authority's view of the scheme. Where is the civic energy and thirst for urban quality to match the public relations and branding of waterside regeneration? Scotland's history and heritage, from the 18th century on, is strongly characterised by inventors, managers, benefactors and doers - by people who were, to a quite remarkable extent, able to make things happen anywhere in the world. Not just headliners like Thomson, Adam, Miller, Mackintosh, Raeburn, Burrell, Carnegie, but phalanx after phalanx of equally significant creators. The creators of the original Scottish waterfronts, for example, engineers and architects of great determination and purpose who made things happen with a sense of pride in the places they were improving and expanding.

I admit to a primal fascination and admiration for Scottish industrial architecture. My worship of, say, Louis Kahn, is fully matched by my obsessional regard for the industrial buildings of the Clyde, or the jute mills in Dundee: Cox's Stack, the Camperdown Mill, the Verdant Works, the Tay Spinners Mill in Arbroath Road, the Ashton Works, requisitioned to manufacture ten million jerrycans during the second war. There was a boldness to these buildings, and their locales; a sense of challenge, and a demonstration of ambition to those outside Scotland.

But does the present, in certain Scottish waterfront schemes, have a future? In these vitally important post-industrial urban milieus, Scottish architectural talent is being vaporised in a commissioning climate characterised by a lack of ambition that will effect quality of life in these places for the next two or three decades.

I wonder if Glasgow's planners took the trouble to study successful waterfront regeneration in cities such as Portland, Oregon. Here, the crucial role was played by new infrastructure and public realm strategies, which have very successfully braided the waterfront to the city.

Key waterfront schemes cannot succeed without the visionary leadership of planners or developers - preferably both. South of the border, planners and developers like Sir Howard Bernstein and Sir Stuart Lipton took hugely bold decisions that completely re-set the bar in terms of the comprehensive redevelopment of key tranches of Manchester and the City of London. Both understand the critical importance of basing regeneration on significantly improved infrastructure. They realised that if new urban connections and public realm were exemplary, the quality of subsequent new architecture would be far better - not least because regenerated areas would be genuinely attractive, and more valuable, rather than merely expedient, stand-offish parcels of real estate.

The placemaking poverty of some high-profile Scottish waterfront projects is sharply highlighted by sharply contrasting pockets of excellence elsewhere. Projects related to Clydebank URC are admirable, for example; and I imagine Urban Splash's involvement with the Irvine URC will bring interesting dividends. We should note that this particular developer's successful dockyard regeneration in Portsmouth was founded on a significant preparatory investment in properly connective infrastructure.

On Scottish waterfronts, blocked architectural talent and potentially catastrophic lack of visionary leadership and infrastructural commitment is producing ostensibly regenerative Big Bangs that turn out to be degenerative whimpers. To use an automotive analogy, the transmission of ideas is shot in these cases: the appraisal of masterplans and architectural quality by planners and developers is not itself being appraised effectively enough. The communication of strong masterplanning and architectural ideas is failing.

Where are the great doers? Why has the perception of Scotland as a reactor-core of obdurately determined architectural creativity paled? Where are the risk-takers, the effective polemicists (and they must include planners, developers, and lobbyists) whose uncompromising visions will produce great buildings and places? It's almost half a century since Colin St John Smith, one of English architecture's great intellectuals, referred admiringly to the Brutalist churches at Glenrothes and East Kilbride by Gillespie, Kidd and Coia as "two ranging shots across our bows from somewhere way over the horizon." Today, GKC's clarion call to produce "a more present and legible space" echoes mordantly around the waterfronts of Glasgow and Leith.

I would not wish these views to be seen as coming from a chaise longue south of the Tweed. After more than two decades of practice (and I began with Spence in Edinburgh) I'm entirely aware of the machinations involved in big urban redevelopment projects. I'm also aware that, sometimes, they are insuperable. But meaningful schemes can usually be developed in even the most complex urban, historic, infrastructural or stakeholder situations. My practice's involvement in the massive King's Cross Station redevelopment scheme has covered ten years; our regenerative scheme for London's Roundhouse, and for the restoration and extension of Mendelsohn and Chermayeff's De La Warr Pavilion at Bexhill, each took a decade to push through. Quality was successfully fought for in both cases.

If the development of Scotland's urban waterfronts becomes an exercise propelled by purely commercial dynamics, and superficial perceptions of what passes for "stylish and liveable" new places, then city margins on the Forth, Clyde or Tay will surely become little more than chunks of characterless urban velcro - unpresent, illegible and shamefully unworthy of Scottish architectural, planning and entrepreneurial talent.