Goodbye to the Distillers Building

5 Jun 2008

PoMo? A developer's plans to demolish the Distillers building by RMJM has provoked a great deal of discussion about the merits of this building which has barely come of age. Mark Chalmers visited the vacant building to find out if the HQ had stood the test of time

This is Edinburgh’s unluckiest building. It was once home to Scotland’s largest PLC: the mighty Distillers Company. Yet almost as soon as it was completed, Distillers ceased to exist. It was bought over by Guinness, and Diageo emerged from the shotgun marriage; however, the new combine’s head office stayed in Ireland. As a result, this orphaned building fulfilled little of its potential as a world headquarters.

Later in its ill-starred life, the building became the headquarters of another Scottish drinks giant, Scottish & Newcastle Breweries. In an unusual excambion deal, S & N were to move from Ellersly Road into another neglected modernist totem, the former Scottish Provident HQ in St. Andrews Square. It had been renovated, but had lain empty with a taint of ‘unlettable’ colouring it in the agents’ eyes. The move had barely happened when the beer company was swallowed up by rival brewers from the Continent. History repeated itself, and this significant building on Ellersly Road now stands empty again, little more than twenty years after it was completed.

When it opened in late 1985, Distillers’ new headquarters marked several key shifts in Scottish architecture. It began life in the offices of RMJM, five years earlier, as a concept. It was intended to take RMJM’s university and public architecture of the Sixties and Seventies into a new expression. With hindsight, academics have tagged it as post-modern, although it is a natural progression of Robert Matthew’s ‘National Movement’. Where the practice’s earlier buildings were faced in rubble and timber to create a modern vernacular, rooted in rural and small burgh prototypes, the Eighties saw this shift into a modern equivalent of the New Town’s architecture. Fittingly for a leafy Edinburgh suburb, this building has a sense of urbanity and polish.

Inside, Distillers demonstrates precise geometrical control; a clear vertical hierarchy which reflects the company’s own organising principles; carefully-proportioned spaces formed to maximise the effects of natural light, and an envelope of smooth-faced ashlar – the qualities of a Georgian townhouse, infact. Yet the biggest shift of all was the confidence to build timelessly. With bronze baluster fittings, stainless steel and oak roof trusses and marble linings to the stairs, Distillers feels solid in a way that few Modern, and virtually no contemporary buildings do. It was commissioned as an expression of one company’s corporate culture – Distillers was a deeply conservative, almost patrician organisation – and that manifested itself in the building’s planning, as much as the permanency of the finishes and detailing.

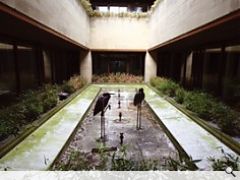

The careful sequencing of internal spaces is one thing which strikes you as you walk through the empty building. Another is the level of architectural control, which sets it apart from almost any other office building in Scotland. A rigorously-applied 1.8m planning grid generates cube and double cube-proportioned offices, and the structure is accommodated within a tartan grid. As far as you can tell, the grid is uncompromised, which is a mighty achievement. The sequence extends from a reception hall with its astonishing sculpture, beyond which you are drawn by the real revelation of Distillers: its quality of light. The building pulls you upwards and outwards towards views of the Pentland Hills, past vista stops set up at the end of each corridor, and over landscaping which flows downhill in a series of terraces.

The stair towers feel unaccountably different to those of other buildings – then you realise that the internal walls, as well as the external envelope, are lined with glass. The large expanses of Pyrostop emphasise that this building is about quality, with no corners cut: and that is perhaps the only criticism, that parts are too lavish. Compared to the contemporary headquarters of Scottish Amicable at Stirling, or General Accident’s head office in Perth (both of which have been taken over by other companies, incidentally), Distillers has a more expensive palette, and at times is over-articulated, such as the exposed trusswork in the chairman’s office, which is busily engaged in resolving two conflicting geometries. However, these occasions are rare, and don’t really detract from the overall scheme, which uses a consistent vocabulary.

Historic Scotland concurred when they were consulted, noting that “the gridded towers recalled the architectural language of Charles Rennie Mackintosh. It is thus linked to a national revival in the same spirit as Alvar Aalto’s later architecture.” In fact, Patrick Hannay (reviewing the building for the AJ in early 1986), noted that its lineage is closer to that of Frank Lloyd Wright, with a powerfully horizontal, stepped section; a deep fascia with large overhanging roofs; and terraces which slide into the ground. Both heritage body and commentator agreed that buildings of this type and quality are rare in Scotland, and Distillers arguably represents the best of its kind.

On reflection, the story of the Distillers building is as much economic history as architectural heritage – the lesson here is that you must have blue chip companies owned and based within your country, otherwise no-one will commission the high profile, high value buildings which we prize. The wealth-generators are great patrons to architects, and we will miss them when they’re gone.

|

|