Biennials at Venice and Liverpool

15 Oct 2004

Last month saw the launch of two important international cultural events; the visual art Biennial in Liverpool and architecture Biennale in Venice.

La Biennale di Venezia, the world\'s most significant architecture exhibition, is set against a backdrop of 16th century buildings. Architects and architectural enthusiasts come to view the work of designers that will set the agenda in towns and cities across the world for the next fifty years. Venice has been home to a visual arts Biennale, the Mother of all Biennales, since 1895. The architecture Biennale has been filling in the alternate years since it was launched in 1980 at the birth of Postmodernism.

The Liverpool Biennial is much younger than its Italian counterpart - this is just the third Liverpool Biennial. The show is composed of four parts; John Moores (a long running painting competition), Bloomberg New Contemporaries (an exhibition of the UK’s best students and graduates), Independents (a platform for artists from the region) and the most significant component, the International. The International 04 consists of forty newly commissioned artworks by a broad range of artists including Yoko Ono and Takashi Murakami, the Japanese artist that brought us Mr DOB, a mutant Mickey Mouse and reinvented the Louis Vuitton brand.

The Venice show takes place on two key sites; in the permanent national pavilions located in the Giardini, a shady waterside garden on the edge of the Grand Canal. The Italian Pavilion dominates the show but the British Pavilion, a Neo-Classical structure that exudes \"empire\" and \"culture\", sits on one of the garden\'s main axes. The second half of the show is just around the corner in the breathtaking 16th Century old Arsenale ropeworks, part of the old naval dockland. Here, the director of the Biennale, Swiss academic Kurt W Forster, gets a chance to identify the significant trends in contemporary design. Hundreds of exquisitely crafted models and drawings fill the old crumbling industrial warehouse.

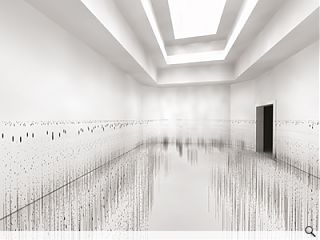

A second narrower leg of the Arsenale, the Artiglierie, is dedicated to smaller shows, most of them from emerging nations (Estonia, Latvia, Ireland) that lack a permanent presence in the Giardini. This year, for the first time, Scotland has a show. Landforms, an exhibition curated by The Lighthouse and designed by Glaswegian architects NORD, covers 17 of the best buildings produced in Scotland in recent years. Featured projects include The Lighthouse, the Scottish Parliament building, the Museum of Scotland and the Mount Stuart Visitors Centre.

In Liverpool, as in Venice, the exhibitions are immersed in the city. In Venice’s case they sit in a relatively discrete area, in Liverpool they are spread far and wide with 53 venues showing work. Venice is purpose-made to be navigated on foot (or boat) and Liverpool isn’t. (I stood for what seemed like a lifetime waiting to cross Liverpool’s Strand, the busy road that divides the docks from the rest of the city, fantasizing about the city commissioning a footbridge for this important crossing.)

Playing the flaneur, the wondering-consuming individual in the metropolis, is so easy in Venice you have to pinch yourself. In Liverpool you have to work harder, but at least there aren’t all the distractions of Venice - you can focus on the art. Hopefully in ten years time Liverpool will have developed the pedestrian infrastructure to support its art show.

Liverpool and Venice were both born out of maritime trade, but comparing the two cities and their shows is not a particularly useful activity, for a start the budget for the Liverpool show must be peanuts in comparison to the Italian’s. However, attending both shows does focus attention on the growing number of international shows - biennials and triennials - that are emerging as part of city marketing campaigns and the kind of work they are producing. One work on show at the Tate Liverpool, SUPER(M)ART by Navin Rawanchaikul poses the tricky question: What does it mean to be Capital of Culture?

“The proliferation of large biennial exhibitions around the world over the last twenty years has created new kinds of opportunities for artists. As a result, there is now an expression ‘biennial art’. “The expression implies an art targeted at a market (visitors and collectors) bigger than that already served by art museums and art fairs,” writes Lewis Biggs, the director of the Liverpool Biennial, in the International 04 catalogue. Some would argue that there such a thing as ‘Biennial architecture’, buildings designed for international exhibitions rather than the construction site. Many of the design journalists reporting from Venice were weary and jaded. As a Biennale virgin, I had to work hard to temper my enthusiasm for fear of being considered frightfully naive. An energetic visitor to the Venice Biennale can learn more in one weekend than they could by reading a hundred books and attending a year\'s worth of public lectures.

At the Giardini most of the national pavilions provided statements on important issues for the day. Concerns about low population growth (Denmark), suburbanisation (US and Netherlands), failing infrastructure (France) and the alienated individual or Otaku, computer Nerd (Japan), were pervasive. The response was a greater emphasis on master-planning and multi-functional complexes.

Metamorph, Kurt Forster’s show was full of Foreign Office and Tschumi folds, Alsop and Acconci blobs, Eisenman’s and Hadid’s slashed landscapes and excessive cantilevers. Such iconic structures are getting a bit of a bashing at present. Just a year ago we might have celebrated the fact that these architects were stretching the limits of what is possible, now the whisper is that the majority are un-buildable. (Forster had made no attempt to distinguish between built work and those that were never likely to leave the drawing board). Architecture and its critics seem to be undergoing a ‘Back to Basics’ moment. Good causes and restrained European modernism are considered healthy and all of that hyper-imaginative, morphed-computer generated stuff is a bit decadent.

Liverpool’s exhibition was more diverse than Venice’s and has met with gentler reviews. The Biennial sets out to put Liverpool on the map, but unlike Venice, it doesn’t make too many big statements about the future of art. The International is the most important show and one of its driving themes is the issue of an international art show’s relationship with Liverpool, the local and the global. As a result, most of the work has an immediate quality. There are no grand gestures, just responses to place and local people.

Some of the most successful works of this kind are Swirl by Valeska Soares, a dance installation completed with real ballroom dancers, the unsettling Retrieval Room and Evidence Locker by Jill Magrid, footage of Magrid in a red coat caught on CCTV cameras throughout the city and architects will no doubt find Iceberg by Inigo Manglano-Ovalle appealing. ‘Liverpoll’ by Feminist and political activist Sanja Ivekovic looks at the concept of the public and phoney participation. She asked Liverpudlians as series of questions and posted the results as pie diagrams-cum-benches around the city. Is there a future after capitalism? she asked. “Yes”, said Liverpool. The vast majority of people voted in favour of a statement ‘there is no such thing as the public, only myriad ‘ members of the public’. Which raises another question - If there is no such thing as the public, where does that leave public art?

Read next: The Winners

Read previous: The Nominees

Back to October 2004

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.