Maggie\'s Highland Centre is soon to open in Inverness

19 Nov 2004

by Penny Lewis

Maggie Keswick Jencks set up the Maggie’s centres charity in order to create a place where people suffering from cancer could receive support and advice. Maggie’s immediate legacy was Richard Murphy’s stable conversion at the Western General in Edinburgh. Since then the charity has opened two more centres and commissioned others from high-profile architects, including Zaha Hadid and Daniel Libeskind. Maggie’s original brief to Murphy was for a place that “would feel like a home” but one that “you wouldn’t quite dare build yourself”. In other words, the building should be intimate and special. In her brief Maggie had identified a new building typology, a therapeutic building.

Establishing a balance between “simple” and “special” is not easy. The first two Maggie’s centres were built within the shells of existing buildings, so the architect had a given discipline. Last year the charity opened its first brand new centre in Dundee by Frank Gehry. A small timber building with a complex timber roof structure and an open organic floor plan. Work is nearly finished on a centre for the Highlands in Inverness by Page and Park architects. Like Gehry, Page and Park have opted for a highly expressive roof structure.

Calum Bennett is Edinburgh Structures Manager at SKM Anthony Hunts, the structural engineering practice formed following mergers between Bradford and Kirkman, Sinclair Knight Merz and Anthony Hunt Associates. Bennett has been working on Maggie’s Highland centre since 2001. He describes the job as a “fusion of engineering and architecture”. Over the past three years the project has given him a few sleepless nights and a great deal of satisfaction. “It has become a labour of love for ourselves and for all those involved,” he says. Bennett and Shahram Hemmati, his colleague, linked up with the building’s architects, Page and Park, early in the design process.

In the early stages of the design, Bennett and the design team considered building the form in both concrete and timber. As the design developed, so too did the engineering. “When we looked at the complexity of the timber shuttering for concrete we thought, could we actually go the extra mile and make timber perform the structural tasks? Concrete might have been an easier structure for us to design but more difficult for the contractor to build and probably more costly. There was a desire for Maggie’s to follow a sustainable theme and timber suited that,” recalls Bennett. In reality the structure does contain two steel wires that were put in to restrain any excessive deflection on an ambitious cantilever. Bennett calls them his “belt an braces” and argues that, now the structure is in place, they have proved to be redundant. Bennett is confident in the design but thinks that in such a complex project two steel wires are acceptable.

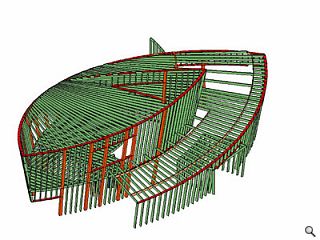

The building form is best described as a piece of orange peel or a short spiral. On plan, the building looks like an eye. Inclined walls splay out and wrap around the building to form part of the roof while the end of the spiral cantilevers over the centre of the building. Each element of the roof structure is lined up along six arcs or radiuses that all share a common focal point. “There are over 3500 individual pieces of timber, each one a different length, orientation and a different angle of inclination,” says Bennett. There are six radiuses inclined at 10 degrees.

Once the basic form of the building was fixed, SKM was able to start modelling the structure. They looked at the advantages of a timber and steel hybrid but eventually opted for timber alone. They commissioned Carpenter Oak and Woodland, a highly experienced manufacturer and carpenter based in Angus and Chippenham, to build the structure in Spruce. “Very quickly Carpenter Oak bought into the labour of love. The challenge was how we were going to connect 3500 pieces of timber, every one at a different angle, when ordering bespoke brackets was not an option,” Bennett explains. SKM worked on concepts, sketched the structure and discussed it with the carpenter. “It was all measured out by the carpenters, using Pythagoras, trigonometry and traditional construction techniques. We learnt an awful lot from them about the approach to setting out the building.”

Charley Brentnall, Chairman of Carpenter Oak and Woodland recalls that the main challenge of the project was the mental process of setting out the roof rather than the craft of putting it together.

The structure was designed and tested using a structural model called Masterseries. The programme imports CAD information into a system that can test the structure’s performance. First, Bennett looked at how the structure would behave in steel in order to identify the system’s weakest points. “We create a model, apply some notional loads, put some bracing in and look again. This process allows us to explore the weak points; each time we extended the bracing we reduced deflection. When we introduced a very stiff beam all around the top of the structure the deflection was reduced to an acceptable level. Bracing in the roof and the wall is used to stop the rotation of the structure,” says Bennett.

Although the structural drawings indicate bracing, the final design uses stressed skin technology rather than conventional bracing. “Stressed skin technology is nothing new but when you add in radiating planes and radiating roofs then there are no guide books. The basic principle is that there is strength in a composite wall, a timber stud with plywood glued and screwed either side. The plywood increases the stiffness like the flanges of a steel beam.” For a normal stud you can get an extra 20 per cent strength by using the ply. The structure also incorporates I beams from James Jones with the stressed skinned technology.

The biggest engineering challenge came from the four metres timber cantilever that projected into the centre of the building. “Usually you would only expect to get a four-and-a-half metre beam out of timber, rather than a four-metre cantilever. The cantilever is formed by a large box beam that spans ten-and-a-half metres. The word to describe them is ambitious,” says Bennett. For the fixings between the structural members, SKM and Carpenter Oak worked to develop a scarf or spliced joint that relies on friction and a hardwood wedge.

Even though the centre is nearing completion, it is still possible to read the structure on both the inside and outside of the building. The copper cladding is laid to reflect the lines of the roof structure and internally the structure stands proud of the occasional vertical element, like the entrance lobby. There is a continuity of structure throughout the building, so that the line of each wall stud lines up with a corresponding roof joist.

“To be honest, we tried to create an extremely challenging building in timber but we didn’t want things to get in the way that could over-complicate things. If someone walked into this building they would say, ‘Wow’. Then if you told them that it was all timber that would be the icing on the cake,” says Bennett.

“The challenge was how we were going to connect 3500 pieces of timber, every one at a different angle, when ordering bespoke brackets was not an option. SKM worked on concepts, sketched the structure and discussed it with the carpenter.”

Client: Maggie’s Cancer Caring Centres

Architect: Page and Park

Structural Engineer: Sinclair Knight Merz - formerly Kirkman and Bradford SKM

Quantity Surveyors: Thomas & Adamson

Carpenters: Carpenter Oak and Woodland

Main Contractor: AWG Construction Services Ltd

Read previous: Future residential developments in Manchester city centre

Back to November 2004

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.