Happy New Year, and Happy New Decade.

You may have come across the term "fifth elevation" – it's what architects sometimes call the roof, although this elevation is rarely seen unless you're high up in a skyscraper in New York or Hong Kong, looking down. I share the passion of "rooftoppers" who explore the city’s heights, and I've particularly enjoyed getting onto the roof of the occasional tower block, mill or power station at dawn.

From the rooftop, you readily grasp Henri Lefebvre’s idea about being simultaneously within, and outside, the city’s rhythms. At street level, you are still part of the city, but on the roof you place yourself apart from it, watching the currents of traffic and the light rising over the horizon. Patterns emerge in the roofscape, and you wonder idly whether they were intended or not: nonetheless, when viewed from above the city becomes a collective artwork.

We often disdain teenagers, glued to their smartphones and instantly reacting to events via Facebook, Twitter or Instagram. But having got back home from today’s RIAS Convention in Edinburgh, I reflected on what I saw and heard there. For me, Amin Taha was the highlight, thanks to his architectural insights and well-paced delivery.

Taha’s career so far has produced a number of well-resolved buildings which have brought him increasingly larger and higher profile commissions around London. Each one builds on his serial investigation of materials, so far exploring the nature and possibilities of non-loadbearing brick, of load-bearing stone, and now embarking on a journey to discover the possibilities of sheet brass and bronze.

Taha presented his take on the Etymology of Architecture, starting with a potted history of art and architectural history. Giorgio Vasari was arguably the first art/ architectural historian with his encyclopedia of artistic biographies, “Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects”. It anecdotally recorded the process of creating art. Two centuries later came Johann Winckelmann with his “History of the Art of Antiquity” and its follow-up volume, which additionally offered some opinions about the work. Perhaps that was the birth of naive architectural criticism.

Taha’s reflections on those books sets his own work into a context: he’s conscious of the Art Historical Industry and aware of the labels it coins. Perhaps there’s a Post-Modern (or post-Venturi) knowingness to his buildings. That said, the remaining half hour covered the evolution of his work, through housing at Barrett’s Grove, Bayswater Road and Upper Street – all of which explored in different ways how CLT (massive timber) construction could provide a more economic structure than concrete or steel frame. In cities like London, most of the development cost actually pays for land, not the building which sits on it.

Most of Taha’s insights came in the form of asides about technique and building economics, such as the housing development at Upper Street in London where the client initially approached Daniel Libeskind, but found him too expensive. The building was completed for around £3000 sq.m., whereas Libeskind was hoping for a budget of at least double that. Shades of the supermodel who wouldn’t get out of bed in the morning for less than £10,000…

Next Taha touched on a Metro station in Sofia, before going into detail about Clerkenwell Close, his home and the office of his practice, Groupwork. The initial concept involved creating a bronze exoskeletal frame, but it was eventually built using trabeated Portland stone. The natural face of the stone is expressed where many would saw it to form a veneer, then dress or flame finish its face. The result is both startling and obvious, although the local Planners evidently hated it so much they fought in the courts to have it demolished.

In a world where we’re rightly pre-occupied with climate change, social and political issues, it was nevertheless good to hear someone speak with clarity about architectural language and materiality. To paraphrase Amin Taha's sign-off at the end, “Let the materials drive the architecture”. I’m glad the RIAS invited him to Edinburgh, where he studied architecture years many ago, and I hope he eventually gets the chance to build in Scotland, too.

Soon after I moved to Aberdeen, I bought a cheap Kodak digital camera. As I recall, the first building I took a photo of was Marischal College. At that point in the early 2000’s, the college was an under-used part of the University, but it dominated Broad Street like a mescaline-laced wedding cake. I particularly liked it on dull days after rain, when the grey granite took on a sheen, although my photos didn’t do it justice.

Later, I returned with a better camera to take a shot of the pinnacles. I zoomed in to look at detail which seemed almost fractal, which kept on increasing as you looked more closely. If you don’t wonder at how many tens of thousands of hours were spent carving the granite, you’re not looking at all.

A year or two later I began contributing to a magazine called “Leopard”, which was published in Aberdeenshire. Over the course of the next few years I wrote about the life and work of many architects who built in the North East, including Pirie & Clyne, Robert Matthew, Leo Durnin and Michael Shewan. Eventually Leopard was sold, and publication ended before I managed to complete my article about Alexander Marshall Mackenzie, the architect of Marischal College.

I know intuitively that Mackenzie had presence. If you think Mackintosh dressed like a dandified fop, photos show the young Mackenzie as a Victorian psychobilly with a pimp moustache, little quiff and giant sideburns. Something like Wayne Coyne, but sent half a century back in time from the Flaming Lips to the place where John Byrne’s Slab Boys grew up.

The hairstyle fixes Mackenzie in time, in same way that his wide-lapelled tweed jacket does; yet fashions in clothing come around again in a way that architecture doesn’t. The Bauhaus was founded exactly a century ago, but just a few years beforehand, in 1906, Mackenzie completed the final wing of Marischal College. It was built in a strange and driven version of High Perpendicular Gothic which has never come back into vogue.

The college is perhaps the ultimate building in Kemnay Grey, the best-known Aberdeenshire granite. Marsichal College will hopefully stand for all time as a memorial to Mackenzie, and to the granite industry my grandfather worked in, which has all but gone. In the 1950’s when my grandfather began working at Kemnay, dimensional stone was still being cut, but by the time he retired in the 1970’s, that had finished.

There was a brief flash of hope when a face at Kemnay’s No.2 Quarry was reopened to win stone for the parliament at Holyrood, but that proved to be the very end. Yet the mercurial silver stone built so much of Aberdeen: His Majesty’s, the Town House, Holburn Viaduct, the Citadel, the General Post Office, Queens Cross Kirk, the old Palace Hotel, most of Union Terrace … and the icing sugar filigree of Marischal College, mostly erected during the 1890’s but continuing past the turn of the century.

Kemnay Grey was later used in the former Scottish Amicable and C&A buildings on Union Street, the Majestic Cinema, the Cowdray Hall, Hilton Kirk, King George IV bridge, and finally as a cladding on Norman Foster’s Faculty of Management at Garthdee. Further afield, it clad the upper storeys of the Royal Liver Building on Liverpool’s Pierhead, it paved Electric Avenue in Brixton, it built Albert Richardson’s Tormore Distillery, it lined the waterways of both Loch Katrine Waterworks and the Lochaber Hydro-power scheme, and Kemnay granite also founded the Tay and Forth Rail Bridges.

In London alone, the Tower, Blackfriars, Southwark, Vauxhall, Kew, Chelsea and Putney Bridges, plus the Thames Embankment, are all Kemnay stone. As it happens, Mackenzie also worked in London, and may have won lots of commissions both before and afterwards – but never built anything like Marischal College again. And neither has anyone else.

It’s post-modern, but eighty years before its time, caught somewhere between William Burgess’s neo-medieval Castell Coch and Philip Johnson’s Pittsburgh Glass headquarters. Those who came before as architecture writers in the North East, such as Douglas Simpson, had their own thoughts about Marischal College. Carving its spirelets, crockets and archlets, “involved a tormenting of granite in a way to which the hard crystalline stone is basically unsuited”, yet Simpson felt that the building with, “a great glistening front, with the deep shadows cast by the bold buttresses, is nothing short of magnificent.”

The closest I came to discovering what Mackenzie’s contemporaries thought was a fusty book dug out in a bookshop in a one-horse town way up Deeside. Briefly excited I drew it from the shelf, but soon calmed down when I saw its condition (mildewed covers and foxed pages), the content (more about dignitaries than architect) and the book dealer’s optimistic pricing. It may still be there on the shelf, gathering dust.

Meantime, in a city where the grey granite provides a kind of visual unity, the college still does its best to stand out. Marischal College’s conversion into council offices a few years ago hasn’t done much for it; the interior was gutted and the facade retention and stone cleaning has left something that looks like synthetic stone.

Everything changes: “Leopard” is extinct now. It was swallowed by Scottish Field and disappeared completely with last month’s issue; but if you’re interested in Aberdeenshire’s granite industry, seek out a copy of Jim Fiddes’s book “The Granite Men”. It’s the first book in seventy years to attempt to cover that ground, since William Diack’s “Rise and Progress of the Granite Industry of Aberdeen”.

Considering the enormous publication gap, it’s almost like Aberdeen is simultaneously proud and ashamed of the very stuff it’s built from…

A few years ago, I did some consultancy work for an environmental charity. After a few months, I realised that they hadn’t quite grasped what an architect does. Too late, it dawned on them I could think and draw in 3D as well as looking at procurement and public engagement.

We did have some interesting debates, though. Many of them saw road use as a polar issue. Two wheels good, four wheels bad, eighteen wheels worst of all. Cars were a menace but lorries were the work of the devil. They were all for sustainability, but when I pointed out that we could all learn about sustainability from the clever engineering of firms like sports cars manufacturer TVR, they shouted me down.

Peter Wheeler was a chemical engineer before he bought TVR Engineering and transformed it. History rhymes, and following the news in recent months about Project Grenadier, does it seem so strange that Jim Ratcliffe of Ineos is also going into the car business, to build his own 4x4?

As co-founder, with Mimo Berardelli, of ETA Process Plant, Peter Wheeler built a world-class chemical engineering business from scratch. He identified a need to reduce the dissolved oxygen content of water re-injected into oilfields, and thus reduce its corrosiveness. Using Wheeler’s engineering flair and commercial nous, ETA supplied de-aerators to oilfields in the North Sea and far beyond.

Berardelli and Wheeler sold the business in 1982, providing the latter with the funds to buy TVR. The first of his Rover V8-engined TVRs was introduced the following year: brash cars with high performance and garish paint schemes. Yet the real achievement of TVR was the skill it developed in design engineering.

At its peak, the firm employed approaching 1000 people in a factory at Bristol Avenue in Blackpool which once made kitchen equipment. Among them was a small team of designers and engineers who thrived on ingenuity. Two examples are the golfball door release in the TVR Chimaera, which is housed in the pillar rather than in the door, and the car’s brilliantly simple hard top mechanism.

Another was TVR’s second engine to be designed from a clean sheet of paper, the Tuscan Speed Six engine or AJP-6. TVR Engineering selected an Austempered Ductile Iron (ADI) crankshaft for its combination of low cost, low weight and high torsional strength. As far as I’m aware it’s still the only production application of an ADI crankshaft.

Peter Wheeler’s belief that cars didn’t need ABS or airbags went against conventional thinking. Yet thanks to its roll cage, a TVR could withstand a high speed accident and protect driver and passenger better than almost anything else on the road. “The advantage of basing the chassis on that of TVR's one-make race series car is that there is probably no chassis anywhere in the world that has been so often and so comprehensively crash-tested.”

The car’s structure was a double-deck ladder frame made from large diameter tubes, with outriggers onto which a lightweight composite body was mounted. TVR’s expertise with glassfibre and carbon fibre mats and resins, combined with the triangulated space frame, provided the cars with high torsional stiffness, and huge energy absorption in the event of a crash.

Design was one thing, translating it into production was quite another. As TVR said in one of its press releases, “The very latest high technology has been used, not in the styling but in the design engineering, to enable one of the largest British-owned car manufacturers to produce simple and elegant solutions to the problems of how to hand-build such sophisticated cars in such small volumes.”

Around then TVR developed a system of “low part count” manufacturing – which sounds simple in principle, but wasn’t something I’d heard of before. However, as is often the way, once you’re aware of it being a “thing”, you recognise it the next time you come across it. The next time was reading about a single-engined trainer aircraft, the SAH-1, which was developed in Cornwall during the 1980’s.

The SAH-1 (named after Sydney Arthur Holloway, in the same way that TVR’s AJP-6 engine was named for Al Melling, John Ravenscroft and Peter Wheeler) was flight tested by Pilot magazine in 1984. “Only one radius is used throughout the fuselage so the same forming tools can be used to make all the frames. There are very few individual parts in the fuselage, but heavy gauge light alloy skins are used and these feel firm to the touch.”

Colin Chapman of Lotus is reputed to have said, “Simplify, then add lightness,” in a similar vein to Dieter Ram’s aphorism, “Less but better”. Low part count manufacturing helps to address both. In material terms, a single-piece moulded, forged or cast component is better than an assembled or fabricated part for lots of reasons: simplifying the design helps to reduce manufacturing complexity, so quality improves, there’s less waste, assembly is faster, labour is reduced, costs are lower. CNC milling from the solid or 3D printing can also assist in simplifying things.

Think about that, as you detail a building. The problems almost always happen at junctions and are usually worst where dissimilar materials meet. The more complexity, the more expensive it is to build. Conversely, a lower part count can mean fewer raw materials and less embodied energy, too. For that reason, the future of intelligent design lies in low part count manufacturing. Simpler to construct, more resource-efficient, with less embodied energy, and as a bonus hopefully a visually elegant solution – and we have a sports car manufacturer to thank for that.

The TVR Griffith’s body design and low-part-count manufacturing system were the work of John Ravenscroft, who was in direct competition with Peter Wheeler and his dog, who were in the process of designing the TVR Chimaera at the same time. The often-repeated urban myth is that Ned the dog bit a chunk out of the Chimaera mock-up’s front air dam, and that became a “design feature”…

Both cars were designed in 3D and sculpted from one foam styling buck which was half-Griffith, half-Chimaera. The designs were so well received that TVR built both, and the Griffith went on to win a Design Council award in 1993: “British Design Award 1993, Presented to TVR Engineering Limited on 27 January 1993 at the Design Council to mark the selection of the Griffith, designed by Peter Wheeler, John Ravenscroft, Neill Anderson, Ian Hopley.”

Later, TVR’s Sagaris used lightweight cross-woven Vinylester bodywork, which saved 60kg over comparable glassfibre bodywork which the firm had used up to then, and the Typhon (literally and metaphorically the ultimate TVR) had a steel chassis which was originally designed for 24 hour racing at Le Mans, its rigidity increased by a tubular rollcage plus a lightweight aluminium honeycomb and carbonfibre floorpan.

In fact for sports cars, lightness is one of the most important design parameters, because it improves handling. It’s why the wheels on my own car (which isn’t a TVR…) are forged rather than cast aluminium, saving several kilograms of unsprung weight per corner. Press-forging minimises waste metal compared to machining, and by re-aligning the metal’s internal crystalline structure along natural lines of stress, results in much stronger parts than casting would produce.

As for TVR today? Wheeler sold the company in 2006 to a Russian oligarch, but just like Bristol Cars without its figurehead Tony Crook, the firm soon lost its way. There is a new car which has supposedly been in development for several years, but it doesn’t have TVR’s brashness nor its proportions, especially the Coke bottle waistline. Sadly, with little progress reported over the past couple of years it seems doomed, like the well-meaning attempt to revive Jensen Cars in the late 1990’s…

Yet that shouldn’t detract from TVR’s greatest achievement, pioneering Low Part Count manufacturing which by now should have found countless outlets across many different industries, including construction.

This morning I headed into the city to survey a long-empty shop unit and the basement underneath it.

I like to make sure that someone else is with me on a survey – one Stooge fires the Disto and shouts out numbers, the other Stooge notes them on the plan – but today it didn’t work out. I was on my own for most of the morning. Likewise, I’m always careful to look out for rotten floors, asbestos and live electrics. Yet for the first time I can remember, I nearly got trapped in the building I was surveying.

It started off innocently enough: I pulled up the roller shutter, unlocked the front door and checked the power and the alarm were off, then walked around to get a feel for the place. Enough of the suspended ceiling was trashed that I got a few glimpses of ornate Victorian plasterwork, but the rest of the ground floor was under attack by dry rot and rising damp, probably caused by rainwater leaking in from the abutment with a flat-roofed extension to the rear.

I switched the torch on and headed downstairs. The basement was a labyrinth and split up by lots of cheap 1960’s flush ply doors with Georgian-wired vision panels. Up until that point all the pass doors had been unlocked, but I turned left and went through a pair of narrow leaves fitted with old-fashioned panic bars, took a step forward and they slammed behind me.

I spun around in half a second, but it was already too late. I discovered I was stuck in an internal pend with various locked leading into it, including the pair I was trapped on the wrong side of. It was dark, apart from faint daylight leaking through a fanlight around the corner: the pend was right-angled and at the end were some steps up to a doorway. I kept the torch on and tried a few switches until a bulb overhead came on.

The doors I’d come through opened in the direction I’d just come, so there was no point in trying to kick them in – I’d be kicking against the stops. Another two doors in the pend were also outward-opening and appeared to be screwed shut. So the only way forward appeared to be up the steps to a pair of what I assumed were fire exit doors.

The doors had a panic latch, plus two steel tubes barring them shut. Presumably the building had suffered burglaries in the past, but pity help anyone caught here in a fire. I pulled the rusty bars out of the way, then pushed the panic latch. At first it didn’t budge, but I gave it a big shove and that sprung the doors open. I was outside at least, in another pend, but this time open to the sky and giving onto the street. Relief. But my bag and survey gear were still inside, locked in the building – and I’d left the front door keys in the front door lock. I also knew there weren’t any spare keys…

After standing vacantly for a minute, I headed back to the car, rooted through the boot and found a big screwdriver. I hurried back to the pend. The lippings on the meeting stiles of the locked doors were already slightly chewed, so I rammed the screwdriver in and pulled against it. The door leaf bowed outwards. After a few attempts, using all my weight to lever against it, I managed to slide the screwdriver shank in at an angle then pull it towards me so that it acted on the panic bar.

After a few attempts to jiggle the panic bar with the screwdriver, the doors swung open quietly and without effort as if to say, what’s the problem? I jammed them open against the uneven stone slabs in the pend then stared: they weren’t fitted with floorsprings, overhead closers or Perkomatics. I’m not even sure why they slammed. Perhaps rising butt hinges, yet once wedged open they didn’t strain to close again.

The rest of the survey was an anti-climax after that excitement, but now I know what I always suspected – it isn’t difficult to break into old buildings, if you really need to. Flush ply doors are pretty useless at keeping people out. I’m also reminded of Henk van Rensbergen, the Belgian photographer who explores derelict buildings. After almost getting trapped in a cell inside a long-abandoned barracks after a door slammed, then discovering there was no handle on the inside, he always takes a lever handle and spindle with him on his expeditions.

Ultimately I wouldn’t have been stuck in that pend forever, because I had a mobile phone, a torch, someone knew where I was and would eventually have come looking for me. If they couldn’t help, an emergency locksmith or even the Fire Brigade would. But it does make you think. If circumstances were different, and I was in a remote place, perhaps with no phone reception or a flat battery, a door bolted shut rather than barred…

As one of my colleagues often says (with apologies to Hill Street Blues) – “Let’s be careful out there”. If you’re going to survey in an unfamiliar building, please think about taking a phone, torch and a big screwdriver or one or two other tools, just in case. As this episode hit home, it can happen to anyone.

Searching for a taste of the exotic? 100 years after Modernism began, more or less, with the founding of the Bauhaus, there’s a conventional palette of materials which we still use. Scotland’s traditional materials like rubble masonry, red deal, slate and harling were supplanted early in the 20th century by beton brut, engineering brickwork, blonde timber and stainless steel. They’re still widely-used, even though none are particularly modern any more.

But Modernism had another strand, exemplified by the Barcelona Pavilion and Aalto’s private house commissions in Finland. Those used a richer palette of leather, darker timbers, bronze and marble. Many of the projects which feature in glossy design magazines today still use this “luxury” palette. No MFI kitchens and laminate flooring for them…

At the moment, I’m working on a range of projects including a centre for people with autism, an aviation academy and a Grade A fit-out for corporate lawyers. As you’d expect, the first one conforms to strict guidelines, the aviation project has an engineering bias, and the lawyers lean towards a sombre palette which is radically different to what the computer games developers in a nearby block wanted.

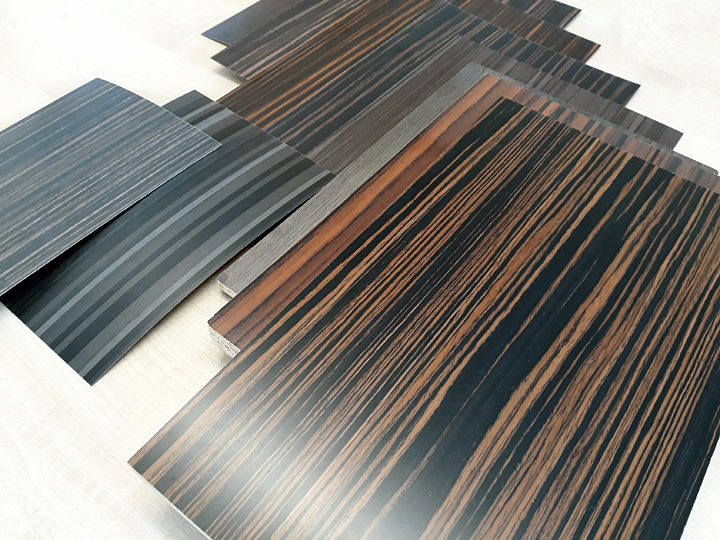

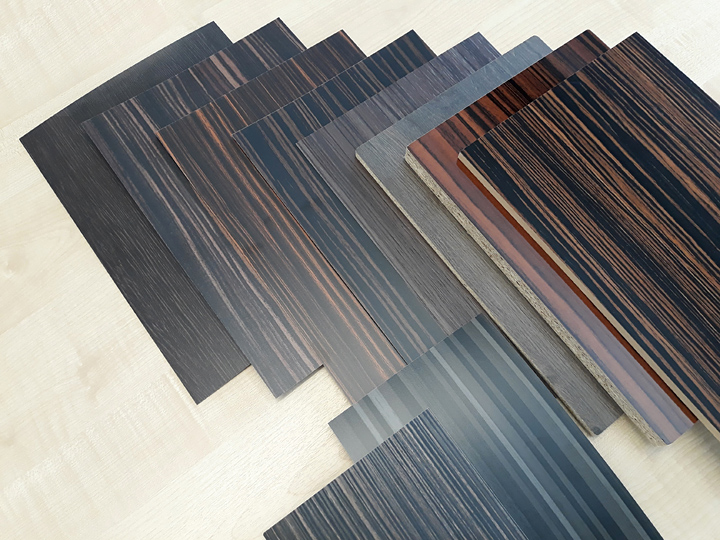

The lawyers’ office suite looks out over the firth, and the internal doors are finished in a veneer which has parallel stripes of very dark brown to black, alternating with lighter bands of golden brown. At first I thought it might be Zebrano, but having consulted the Architect’s Giant Bedside Book of Exotic Veneers, I think it’s actually Macassar Ebony.

Some use “Macassar” for any Ebony with prominent light and dark streaks, but it’s generally acknowledged as Diospyros celebica. Both Zebrano and Macassar veneers came into fashion a few years ago, but remain in the timber trade’s highest price group. For example, Range Rover use Macassar for dashboard and door cappings, even though their Chief Designer, Colour and Materials, Amy Frascella suggested in an interview I read that there’s a shift in favour of reclaimed and non-leather materials in what she calls post-industrial colours.

That might mean vegan-friendly polymers and fake “pleathers”, plus sustainably-sourced timbers or even post-consumer recycled material. For example, waferboard, strandboard and OSB are different names for the same thing, a board pressed from sawmill waste. Carbonfibre is another possibility, at least in sports cars, and various man-made luxury textiles such as Alcantara.

Natural materials have different advantages, but in all conscience some timbers are difficult to spec, because tropical hardwoods grow very slowly. Teak and Mahogany were popular in the 1950’s and 60’s, but that popularity meant swathes of rainforest were felled and we began to seek alternatives, such as Sapele and Jatoba. Yet timber is only truly sustainable if you plant a tree every time you chop one down – and if you’re prepared to wait for several generations before you harvest that patch again.

As I was hunting for a match for the Macassar wood, I spoke to several veneer suppliers, one of which was located in the East End of London. The cheerful Cockney technical rep decided to have a word in my shell-like, as Arthur Daley would say: “That looks like a laminate rather than a veneer, mate – an expensive high pressure laminate, but it’s a laminate nonetheless.” Cheers, geezer.

It makes sense when you understand the context. Macassar Ebony is rare in veneer form because the trees don’t grow particularly tall, so finding boles large enough to cut door-sized sheets of veneer from is difficult. The small sheet size makes the veneer more suitable for cabinetry, inlay work and making musical instruments. Macassar is also a tropical hardwood, which while not listed in the C.I.T.E.S. Appendices of endangered species, it’s definitely on the I.U.C.N. Red List of vulnerable trees.

The trees are native to the Celebes Islands in the East Indies and they’re named after the Indonesian port of Makassar, which was the main point of export. They’re also found in Maluku and Borneo – although back in the day, many shipments came through India and Sri Lanka. Until the 1970’s, Holt’s Blue Funnel line ships called at the less well-known ports of Sumatra, Java, Borneo and often took on cargoes of exotic hardwoods. Nowadays, due to the trees’ rarity and our concern about the sustainability of tropical hardwoods, Ebony is rightly difficult to get hold of.

It was always thus. Ebony wasn’t readily available in Europe until the 1600’s, although the Greek historian Herodotus records that Ethiopia paid an annual tribute of 200 ebony logs to the Persian Empire. After the 17th century, woodworkers in France perfected the craft of veneering with ebony for furniture and cabinetry and even today, France cabinetmaking is called ebenisterie and a cabinetmaker is known as an ebeniste.

So that explains why Macassar laminate is an acceptable substitute for the real thing. After speaking to the cheerful Cockney, I called up Herodotus on the blower - but he was out of stock, and anyhow doubted whether he could get veneer into the country due to the Brexit Effect. So the moral of this story is that we’re in the market for a convincing laminate, weighing the efforts of Formica, Egger, Resopal and Polyrey.

The best match so far comes from Formica, which captures the colour and tone of a real Macassar Ebony, as well mimicking its texture. Whether or not the lawyers realise it, their choice of door finish is a modern facsimile of an exotic tree which is amongst the aristocracy of timbers. In fact, we covet Macassar wood, and its rarity, so much that we’ve almost logged it into extinction.

Beware the Ides of March: Julius Caesar was assassinated on 15th March in 44 BC, Interserve went into administration on 15th March 2019, and things aren’t going well for Theresa May today, either. Somewhere in the south of England, a big red bus is careering towards the precipice of a high white cliff. Better news arrived in the post from the Barbican Centre in London, from which I ordered a copy of “Building the Brutal”, a book of Peter Bloomfield’s photos taken during its construction.

It's a favourite sport among architects to recall what first attracted them to architecture. We had a family friend who ran his own practice, and he offered sage advice when I put my portfolio together for the entrance interview at Duncan of Jordanstone. My art teacher similarly encouraged me, introducing me to a local practice with whom I worked after I graduated: I recently met up with him again for the first time since 1990, which prompted me to cast my mind back further.

When I was in second or third year at secondary school, my parents diverted into Aberdeen each time we drove up to visit my grandparents, so that I could spend half an hour or so admiring the architecture books in Waterstone’s on Union Street. Art and architecture were on a mezzanine floor towards the back of the shop – an area with plush burgundy carpet, black ash shelves and fancy lighting. I still have the books I bought, usually paid for with book tokens received as birthday and Christmas presents.

As I leafed through the Barbican book, I realised something about it had lodged deeply in a recess of my brain. It’s the one place I return to every time I visit London, and it dawned on me there might be a reason for that, beyond the fact it’s an impressive megastructure and quite unique in Britain. “Utopian” is a cliché, and Brutalism has become fashionable nowadays among critics and hipsters - but both applied to the Barbican pretty much from its conception in the late 1950’s through to 1982 when it was completed.

In those days, the Barbican consisted of unfashionable public housing for rent which politicians, trade union leaders and designers lived in. By the 1990’s it had become fashionable housing for sale, with flats going for £200k or £300k. You could just about imagine that if you worked hard and got a good job in London, then saved carefully you might be able to live in one. Now the flats are unattainable other than by the very rich or property speculators. I’m reminded of a short story by Will Self in which a drug-crazed City trader gazes out from his penthouse using binoculars, looking down both literally and figuratively on the proles seething along the pavements, several hundred feet below. Of course, nowadays that scene is just as likely to play out at Nine Elms or Canary Wharf than the Barbican.

Going right back into childhood, I still remember sitting in a primary classroom, drawing an outline of the Barbican onto the satin-textured newsprint paper which Dundee’s Education Department provided by the yard. The pencils were bought from Winter’s in Shore Terrace, a wonderful art supplies shop in a Georgian building. I remember Winter’s creaky door hinges (maybe they were floor springs…) and a mosaic floor across which the assistants heels click-clacked as they went to and from the back shop. As with Waterstones in Aberdeen, I got to know the shelves at Winters quite well, and at some point I switched loyalty from blue Staedtler pencils to green Faber pencils, then to Caran D’Ache.

After a lot of casting my mind back, I’ve concluded that I must have been given a magazine or booklet about London, which had been published not long after the Barbican opened in 1982. Perhaps that was one of the first things which turned me on to architecture, although the unattainable glamour of London may also have had something to do with it. Unattainable to a child, that is. Straining my memory further, I seem to recall the same magazine featured the RAF Museum at Hendon with a roof similar to the arcaded vaults on top of the crescents at the Barbican, and perhaps the terraced blocks beside St Katharine’s Dock.

I have lots of other memories of places visited, but the Barbican has stuck with me. The three dimensionality of the buildings and the interesting skyline marked London as something different: the vast scale of it only struck me when I visited in person. With the benefit of hindsight, the Barbican also seems like a properly-executed version of Park Hill, Cumbernauld Town Centre or the Siedlung Halen in Switzerland, which arguably helped to kick off the craze for mat buildings and megastructures.

So much for memory lane. Meantime, many of the photos from Building the Brutal are reproduced on the Barbican’s website, here - http://sites.barbican.org.uk/buildingthebrutal/

“It’s like wartime,” complained Mr Wolf, then added, “Not that I’m old enough to remember.”

His technician shrugged and threw a clog of wood into the stove. They were working from Mr Wolf’s house: a temporary arrangement. Their office in the city was cold and dark, because in the last few days gas and power in the city had become intermittent.

Driving in and out to the office was a bad idea, too. Not that the roads were busy; in fact the city centre was quiet these days. There were miles of queuing lorries at standstill on the motorways, the quaysides lined with part-unloaded ships. Their cargoes were trapped in Customs while the politicians argued.

Driving meant burning fuel that may not get replenished, so the interim government encouraged people to use the railway instead. However, a circuit board had blown inside the signal box where the tracks converge on Waverley, and several trains were stuck fast in the gullet. A replacement board had to come from Germany, but the urgently-needed package was stuck in Customs at Dover.

“Well I can’t get to site tomorrow. We’ve only got petrol coupons for next week, and anyway we’ll only get 20 litres at a time from BP. Barely enough to get there and back.”

“No point, there’s nothing going on down there anyway. Last contractor’s report said they’d laid off due to shortages.”

The site had run out of plasterboard weeks ago, truckmixers wouldn’t deliver beyond the city boundary, and copper pipework was like gold dust. There was talk of building licences being re-introduced, just like during the 1940’s. So Mr Wolf turned back to the internet, which for the moment at least was still working, and tried to source some ironmongery.

There was no point specifying familiar brands; factories were on a shutdown and stocks at the wholesalers had run out. After a couple of hours spent scouring the net and making fruitless phonecalls to ironmongers in little country towns, Mr Wolf struck lucky. He found an ancient business in the Black Country with old stock in its warehouse.

A picture formed in his mind: dusty boxes massed in corners, on shelves, hung from hooks, piled on counters, set out on stands, stood up on the floor, and hidden away in stock rooms … all to be fetched out after a hunt.

The hardware man came back to him: “Many thanks for your enquiry, I went out into the stores to see what I have (and it's very cold out there!) I’ve found two dozen 4" x 2 5/8" DPB washered butts, BMA finish. Old stock, the boxes are tatty but the contents are like new. They’re British made, Arrow Brand.”

“Regarding the actual maker, at the time my company would have bought them, maybe 50 years ago, there were dozens of small manufacturers. Indeed they often made special locks and ironmongery for the larger companies you’re more familiar with. But most of the little firms died out after we joined the EEC…”

Mr Wolf did a quick calculation from metric back into the Imperial measures which the interim government had imposed a few weeks before, along with food rationing and blue passports. “Right then, I’ll take the lot.” Lately came the fear that if you didn’t snap things up when you had the chance, someone else would.

So that was the door hinges sorted – but shortly afterwards the electricity went off. Then the internet.

Mr Wolf was secretly pleased, and turned to his technician: “I’ve reached breaking point with TV and the net. I’ve got a giant lever I’m about to pull. All the politicians, journos and pundits – plus Fiona Bruce – are going to drop into a pit with hungry orcs at the bottom.”

It was 4pm, so he decided to quit whilst ahead and go for food. As he sclytered though the snow, he could hear dull thuds resounding across the firth. Perhaps they were bird-scarers, or wildfowlers blasting ducks from the sky – only now for food rather than sport.

Soon he reached the small supermarket at the foot of the brae, hoping to discover it had received a delivery that afternoon. An old man was tying his dog up outside the shop.

“It’s no easy,” he shook his head, “I cannae even get his food down the Co-Op any mair.” They both looked down at his dog, a long-bodied basset with mournful eyes, droopy leathers and drooling flews. The dog looked up, sneezed and shook itself. Mr Wolf thought it did indeed look hungry, but they always do and besides the dog could do to lose a few pounds.

When he got back from the shop with a giant bag of pasta, a wedge of stale cheese and a dented tin of pear quarters, the technician had packed up and was ready to leave. Mr Wolf nodded and waved him off, “We’ll need to carry on tomorrow and see if we can get some lever handles and pulls.

“From where? Off the black market?”

“I don’t know, I really don’t.” Mr Wolf knew that things weren’t looking good – yet the folk protesting on the streets today and the angry hacks in the tabloids, had all been in favour until the reality struck them personally.

“Yeah, but it’s the same bandits that profit when things go wrong - guys like Arturo Ross.”

“Arturo Ross … now there’s a blast from the past.”

“Aye, I remember him. God. Arturo Ross …”

Next day was cold and bright, so Mr Wolf decided to take his chances with the petrol and see if he could find more hardware.

The client had agreed to keep paying fees provided Mr Wolf could lay his hands on materials. To do that, Mr Wolf had to use all his ingenuity. He fell back on old contacts, called in favours, and even searched in the baccy tin where he’d kept ten years’ worth of business cards, just in case this day should ever come. At the very bottom of the tin was Arturo Ross’s card.

Half an hour later, Mr Wolf pulled his car up onto the unmade pavement in front of an old bleachworks. The whitewash was peeling from the brickwork, and a few windows had been smashed, but the gates were open and machinery was running faintly somewhere inside.

Hi Arturo, how goes it?

Arturo looked up from vat of noxious chemicals. He pulled out a length of metal which steamed and sparkled as it met the air. It was a two foot long pull handle.

Mr Wolf brightened, “Where did you lay your hands on that?”

Arturo cleared his throat and replied vaguely, “A lad called James Riddell.”

“What? You’re taking the piss. Anyway, I’m needing handles, bronze or something that looks like bronze.

“You’ll be lucky son, replied Ross, “though I can mibbe help.”

“I hoped you might.”

When Mr Wolf returned a couple of weeks later with payment, Arturo Ross held out a lumpy package wrapped in brown paper - “These are the last pull handles in Scotland. I hope your client is very happy wi’ them. Cause he’ll no get any mair, no for love nor money.”

Ross ran the fifty pound notes under an ultra-violet lamp (you couldn’t be too careful these days) then added them to a roll held together with a fat elastic band. There was no pale blue or sepia brown, but Mr Wolf got the want of many leaves of purple and magenta.

As Mr Wolf left with his door handles, Arturo Ross was smiling faintly, “What next eh? Martial law?”

For months to come there was no let up in the cold weather: the city was dead and the ice showed no sign of melting.

If you’re searching for a microcosm of Brexit Britain, you could do worse than begin by scrutinising the UK’s widget manufacturers. Over the past few weeks, I’ve scoured the wholesalers on Dryburgh industrial estate for well-designed electrical widgets, or “wiring accessories” as M&E engineers call them.

As I hunted through trade outlets and online, my path crossed with some Buy British enthusiasts, who are on a mission to support the UK economy at this difficult time; shades of Al Murray’s Pub Landlord and his campaign to Save the Great British Pint… So this is a rumination on whether we make stuff any more, and if so, whether it’s any better than what we import.

Buy British is sometimes overtaken by the imperative to Buy Scottish, but there are a few exceptions. You’d think that with two of the UK’s Big Six energy suppliers based here – Scottish Power is headquartered in Glasgow and Scottish & Southern Energy in Perth – there would be a thriving electrical components industry in Scotland? Sadly, no.

Scottish firms concentrate on the heavy end of electrical engineering: Brand Rex at Glenrothes make cables, Belmos in Motherwell make distribution boards, Parsons-Peebles at Rosyth build electric motors, Bonar Long in Dundee used to make power transformers and Mitsubishi Electric at Livingston still makes air conditioning and heat pumps. However, we appear to have neglected the well-designed, good quality switchplate.

“The door handle,” said Juhani Pallasmaa, “is the handshake of a building.” Presumably the light switch isn’t far behind. It’s another point of close contact, yet many switches are made from white moulded plastic, which looks cheap, feels cheap and isn’t made to last. Neither is there any thought given to its environmental impact – so we should listen to Dieter Rams, the German industrial designer about whom a documentary film was released recently.

Rams was Braun’s chief designer from the late 1950’s to the mid 1990’s, and in that time he designed hundreds of products which we’d now call minimalist. He wasn’t a stylist, but approached each product ergonomically, so that it would be well made, long lasting and intuitive to use.

Dieter Rams has been talking about the social, political and environmental impact of design for more than half a century – interestingly, the antithesis of the line taken by late Isi Metzstein, who complained that too much consideration is given to the social and operational aspects of design, as opposed to the architectonic.

Many of the products Rams designed for Braun were made from injection-moulded plastic, which isn’t in the least environmentally-friendly. However, he and his contemporaries didn’t make disposable goods, they made things to last: lots of people have Braun products such as calculators, radios and kitchen gadgets which still work, 30 or more years after they were made. 30 years or more can’t be said for cheap light switches.

It’s rarely worth trying to repair white moulded plastic faceplates when they break, and they can’t be recycled either. Similarly, manufacturing in the Far East then shipping components to Britain is madness, no matter how cheap it is today to stick things in a container. So, bearing in mind environmental impact as well as aesthetics and practicality, the following thoughts come from my experience as a specifier who insists on seeing and feeling samples, and also from listening to electricians and electrical engineers.

Where to begin? I’m told that in the 1960’s, Crabtree accessories were robustly made, albeit rather old-fashioned and chunky in appearance. Then MK Electric produced a slimmer, sleeker style of faceplate which became more popular. However, sockets and switches from the 1970’s and earlier were made from ivory Bakelite, which is pretty much bulletproof, whereas the moulded urea-formaldehyde plastic used by everyone since then is easy to crack.

Recently, a spark took me aside to ask why architects specify MK Logic Plus so frequently. He felt it must just be habit, because while MK Logic accessories used to be "Made in UK", MK was bought by Honeywell a few years ago, and some of its products are now "Made in Malaysia". Their website does say, “MK Electric, unusually for the sector, still manufactures its products for the UK in the UK; with a factory in St Asaph as well as Southend.” The electrician complained that he often had to return MK accessories to the wholesaler, because the fixing screws were jammed solid against the terminals, and he blamed that on manufacturing in the Far East. Perhaps that's just prejudice, though.

Which makes would he recommend? Hager, Contactum, Schneider. Doing a bit of digging, “In the UK, Hager has a well-established R&D team and global resource to meet the needs of the market. This is backed up by the UK factory.” Contactum, “is one of a few remaining manufacturers of electrical wiring accessories and circuit protection products in the UK, and manufacturing still continues today at its factory in Cricklewood, London.” We'll come to Schneider later.

The electrician reckoned that Telco, LAP and Knightsbridge were firms to avoid; according to him they are cheap and appear to be made abroad. So perhaps there is a correlation between where a thing is made and its quality. Is that economic nationalism, “common sense” as Al Murray’s Pub Landlord might put it, or pure prejudice? Many of us are cynical about the quality of imports – in other words, we believe that these things could be made much better than they are.

Personally I used to reach for the MEM catalogue as my default for white accessories – MEM Premera faceplates appeared to be decent quality, looked slim, and a full range of accessories is available. MEM is now owned by Eaton, an American corporation, which shut down its factory in Oldham in 2005.

But compared to white plastic, metal faceplates win every time. They’re not manufactured from petrochemicals, they won’t shatter like plastic does, they don’t turn yellow with age, and “live” finishes such as bronze will develop a patina with use, which we find attractive. Finally, if we’re finished with them the metal can be recycled rather than going to landfill or incineration.

Metal faceplates got a bad rep in the 1980’s when there was an outbreak of Victorian Brass in suburban Britain. Once that subsided, polished chrome became popular, and now in theory you get a brass, bronze, chrome, stainless steel, nickel or copper finish, as well as powder-coated or clear polycarbonate “invisible” switchplates. Most of the major accessories firms offer several ranges in metal, and after some research I discovered that quite a few still manufacture them in the UK.

Wandsworth Electrical produce a “premium designer electrical socket which is 100% designed and made in Britain.” Focus SB sell “Quality Electrical Accessories Made in Britain: we are the only UK company licensed to manufacture electrical accessories for export to China.” So it isn’t all one-way traffic. Similarly, Hamilton Litestat have a Union Jack on their website and offer “largely UK-made products”; M. Marcus manufacture all their accessories at a factory in Dudley; and according to G&H Brassware, “All our products are hand assembled at our premises in the West Midlands.”

But the best-designed products I’ve come across were made in Britain by GET Group. Their sockets and switches were presented in a box with a translucent sleeve which slid back from the carton to reveal a switchplate which followed the same design ethos as the keys on a MacBook’s keyboard. The plate’s corners were neatly radiused, the rocker edges were rounded off and their action was a well-damped clunk, rather than the nasty click-clack of a £2.50 switch.

GET’s accessories were made from steel and brass and high density polymer, and even came with M3.5 screws in two different lengths, to suit different depths of backbox. That level of design thinking is rare, especially at the consumer end of the market. Electricians liked their robustness and the ease with which the terminals could be wired; I guess architects liked their aesthetic, bearing in mind that they were Mac-like, and of course Apple designer Jonathan Ive was heavily influenced by Dieter Rams … so ultimately the widget makers could learn from Rams' design approach and sustainable philosophy.

GET Group plc was swallowed up by Schneider Electric of France a decade ago, and their clever designs have gradually disappeared, which is a great shame. It’s not clear from Schneider’s website whether they still manufacture in the UK, either. That adds to the feeling that well-known firms have been taken over by overseas companies, production moved offshore, and the quality may suffer while the brand trades on its past reputation.

On the other hand, the contract quality fittings which architects specify for higher end projects are quite different to the budget quality you find in B&Q, Homebase et al., and the former are still made in the UK, if not Scotland. They might incorporate sophisticated electronic dimmers, or bespoke finishes which use metalworking skills developed by locksmiths and ironmongery hardware makers in the Black Country.

In conclusion, the future seems to lie in making high value products, yet there doesn’t appear to be a design-led electrical accessories firm in this country any more. Perhaps James Dyson will take up the challenge, having already launched his own ranges of taps and lights …

The next issue of Urban Realm will include a few photos I took ten years ago in an abandoned building which has since been demolished. If you drove down the road today, you’d never know it existed, and that gives the images more meaning and greater power – or perhaps just an innate sense of melancholy for what’s now gone.

I trained as an architect, so it goes without saying that I’m interested in buildings for their own sake; but shooting photos of abandoned places has also made me sensitive to the relationship between the man-made and the natural. That might be how industrial architecture such as a colliery or steelworks sits in the landscape, but also how nature takes back buildings, such as when ferns take root inside a derelict mill.

Years ago I came across a book called “In Search of the Wild Asparagus” and that was one of the rare occasions I’ve come across an author describing an experience I can identify with exactly. In one chapter, the botantist Roy Lancaster rambles over the sand dunes at Ainsdale Beach, and that brought back my own trips to Tentsmuir Point and Buddon Ness, exploring the wartime bunkers and flotsam which the tide had brought in.

In another chapter, Lancaster described how he explored wasteland and bombsites - then went on to discuss the rather commonplace plants he discovered there, such as fireweed, goldenrod and buddleia flourishing amongst piles of crumbling masonry and rusting pipework. Nature and the man-made exist in a two-way relationship which is closer to synergy than dichotomy: you can see exactly that when a plant takes root in a crumbly old wall, or mounds of moss choke up the rones.

Roy Lancaster’s photos show the visual richness of old industrial sites being reclaimed by nature, and I’ve gone back many times to places like this, to root around for interesting objects and textures and juxtapositions to draw and photograph.

As I’ve alluded to before, shooting photos of newly-completed buildings requires a different approach. Many contemporary buildings are visually sterile, lacking the rich textures and colours of decay, but also any sense of time passing and the history implicit in that. Of course, if you shoot photos of cocktail bars and nightclubs, they may have lots of colour, pattern and detail – but for the most part “maximalism” is unpopular in contemporary design.

That leaves you with architectural photography as a study of materials, natural light and proportions and its poorest relation is the Grand Designs House, which is often very reductive and boils down to aspirational people who create the biggest volume they possibly can for the money, paint the interior white, then scatter a few pieces of furniture around. They use industrial cladding and reinforced concrete in the hope it will save them money (it rarely does) and the glazing often consists of huge single-aspect screens which provide great views, but blast the front of the space with uncontrolled light.

Perhaps this sterility helps to explain the appeal of photobooks about abandoned places, but these books have their own hang-up. The authors are desperate to show us places which are “hidden”, “secret” or “unknown”. I wish them well, but in my experience very little is secret any more – the internet has put an end to that, and uninvited visitors with cameras tend to follow in each others’ footsteps. Besides, these mysterious places were someone’s home, workplace or church until a few years ago, and it takes a generation at least for people to forget them.

The search for abandonment is an odd discipline. I know a few people who have travelled far and wide to collect “that shot”, the perfect capture of somewhere which others have been before them. Places like the exclusion zone around the Chernobyl power plant and nearby town of Pripyat in Ukraine, or the former Communist memorial house on top of the mountain at Buzludzha in Bulgaria - http://www.buzludzha-monument.com/

Does pursuing your own version of an iconic photo devalue the photo that you take yourself? No, because it’s still your image and you got the chance to see the place with your own eyes. But it does devalue the intention behind it. The more somewhere is publicised on the net, the less secret it is, and if you chase these chimaeras, you risk becoming the thing which everybody hates – a tourist.

The tourist looks at everything as a photo-opportunity (usually involving a selfie to post on Instagram); the architectural traveler looks at buildings as an opportunity to learn, perhaps from their detailing or materials choices. But I’m still interested in stepping outside the professional architect’s mindset – although I realise that after over 20 years it can never really be switched off – and trying to look at buildings as subject matter, something I can photograph or sketch/paint.

Over the past year I’ve met up several times with a friend who shares my interest in decay and abandonment. Although we both studied at Duncan of Jordanstone, we followed different disciplines and after each trip I look forward to seeing her photos, because she sees the world in a markedly different way. As she said, it’s very obvious our photos were taken by different people.

So far I’ve been surprised and puzzled at how different our subject matter, technique, processing and everything else is, considering we visited the same place at the same time, and watched each other working with the same “content”. Sometimes it’s difficult: although we have much in common it feels like we’re struggling to find a shared language. There is much room for misunderstanding, but we’ve shared a few things already and she’s begun to help me see things differently.

There you go, that’s as much of a positive message as you’re going to get at the end of 2018, while the world outside descends into constitutional crisis and madness. Happy Christmas and all the best for 2019…