Searching for a taste of the exotic? 100 years after Modernism began, more or less, with the founding of the Bauhaus, there’s a conventional palette of materials which we still use. Scotland’s traditional materials like rubble masonry, red deal, slate and harling were supplanted early in the 20th century by beton brut, engineering brickwork, blonde timber and stainless steel. They’re still widely-used, even though none are particularly modern any more.

But Modernism had another strand, exemplified by the Barcelona Pavilion and Aalto’s private house commissions in Finland. Those used a richer palette of leather, darker timbers, bronze and marble. Many of the projects which feature in glossy design magazines today still use this “luxury” palette. No MFI kitchens and laminate flooring for them…

At the moment, I’m working on a range of projects including a centre for people with autism, an aviation academy and a Grade A fit-out for corporate lawyers. As you’d expect, the first one conforms to strict guidelines, the aviation project has an engineering bias, and the lawyers lean towards a sombre palette which is radically different to what the computer games developers in a nearby block wanted.

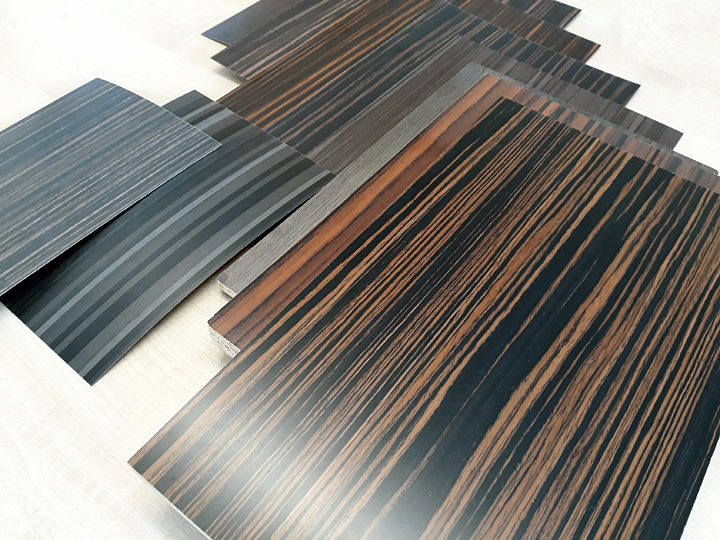

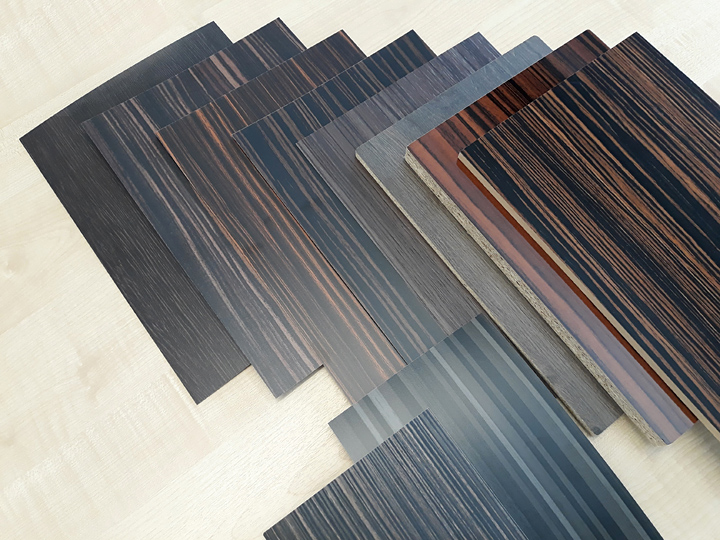

The lawyers’ office suite looks out over the firth, and the internal doors are finished in a veneer which has parallel stripes of very dark brown to black, alternating with lighter bands of golden brown. At first I thought it might be Zebrano, but having consulted the Architect’s Giant Bedside Book of Exotic Veneers, I think it’s actually Macassar Ebony.

Some use “Macassar” for any Ebony with prominent light and dark streaks, but it’s generally acknowledged as Diospyros celebica. Both Zebrano and Macassar veneers came into fashion a few years ago, but remain in the timber trade’s highest price group. For example, Range Rover use Macassar for dashboard and door cappings, even though their Chief Designer, Colour and Materials, Amy Frascella suggested in an interview I read that there’s a shift in favour of reclaimed and non-leather materials in what she calls post-industrial colours.

That might mean vegan-friendly polymers and fake “pleathers”, plus sustainably-sourced timbers or even post-consumer recycled material. For example, waferboard, strandboard and OSB are different names for the same thing, a board pressed from sawmill waste. Carbonfibre is another possibility, at least in sports cars, and various man-made luxury textiles such as Alcantara.

Natural materials have different advantages, but in all conscience some timbers are difficult to spec, because tropical hardwoods grow very slowly. Teak and Mahogany were popular in the 1950’s and 60’s, but that popularity meant swathes of rainforest were felled and we began to seek alternatives, such as Sapele and Jatoba. Yet timber is only truly sustainable if you plant a tree every time you chop one down – and if you’re prepared to wait for several generations before you harvest that patch again.

As I was hunting for a match for the Macassar wood, I spoke to several veneer suppliers, one of which was located in the East End of London. The cheerful Cockney technical rep decided to have a word in my shell-like, as Arthur Daley would say: “That looks like a laminate rather than a veneer, mate – an expensive high pressure laminate, but it’s a laminate nonetheless.” Cheers, geezer.

It makes sense when you understand the context. Macassar Ebony is rare in veneer form because the trees don’t grow particularly tall, so finding boles large enough to cut door-sized sheets of veneer from is difficult. The small sheet size makes the veneer more suitable for cabinetry, inlay work and making musical instruments. Macassar is also a tropical hardwood, which while not listed in the C.I.T.E.S. Appendices of endangered species, it’s definitely on the I.U.C.N. Red List of vulnerable trees.

The trees are native to the Celebes Islands in the East Indies and they’re named after the Indonesian port of Makassar, which was the main point of export. They’re also found in Maluku and Borneo – although back in the day, many shipments came through India and Sri Lanka. Until the 1970’s, Holt’s Blue Funnel line ships called at the less well-known ports of Sumatra, Java, Borneo and often took on cargoes of exotic hardwoods. Nowadays, due to the trees’ rarity and our concern about the sustainability of tropical hardwoods, Ebony is rightly difficult to get hold of.

It was always thus. Ebony wasn’t readily available in Europe until the 1600’s, although the Greek historian Herodotus records that Ethiopia paid an annual tribute of 200 ebony logs to the Persian Empire. After the 17th century, woodworkers in France perfected the craft of veneering with ebony for furniture and cabinetry and even today, France cabinetmaking is called ebenisterie and a cabinetmaker is known as an ebeniste.

So that explains why Macassar laminate is an acceptable substitute for the real thing. After speaking to the cheerful Cockney, I called up Herodotus on the blower - but he was out of stock, and anyhow doubted whether he could get veneer into the country due to the Brexit Effect. So the moral of this story is that we’re in the market for a convincing laminate, weighing the efforts of Formica, Egger, Resopal and Polyrey.

The best match so far comes from Formica, which captures the colour and tone of a real Macassar Ebony, as well mimicking its texture. Whether or not the lawyers realise it, their choice of door finish is a modern facsimile of an exotic tree which is amongst the aristocracy of timbers. In fact, we covet Macassar wood, and its rarity, so much that we’ve almost logged it into extinction.

No feedback yet

Contact | Help | Latest comments | RSS 2.0 / Atom Feed / What is RSS? | Powered by b2evolution

This collection ©2025 by Mark Chalmers | b2evo skin | evoCore