Laurieston: Another Brick in the Wall

29 Oct 2014

It has been heralded as an exemplar project pointing the way forward to a new era of public housing but can this level of investment be sustained? Urban Realm took a look to see whether Laurieston holds the key to both the housing crisis and dragging up design standards. Images by Macateer Photography

As the first tenants take stock of their £90m surroundings at the heart of the Laurieston Transformational Regeneration Area bystanders could be forgiven a sense of déjà vu - we have been here before with the infamous Comprehensive Redevelopment Areas of the 1960s after all. If there is one thing Glasgow does not lack it is confidence however so it is hardly surprising that the city should be hoping it’s third time lucky in building a sustainable future for the area with what is billed as the biggest Scottish housing association development this century.Initial proposals for regenerating the area were first drawn up in 1994 but it has taken but it has taken the bulk of the intervening two decades to complete just this first phase of 201 homes, the first new houses to emerge in Laurieston since the 1970s. Supplanting the grim tomb stones of Norfolk Court for something more akin to the scale and massing of the long-gone tenement estates which preceded it this is a district going back to its future.

This embrace of the past sees a formal grid typology adopted with public streets running parallel with secure back-courts. In a break with the past however each home’s living space is now arranged around an external balcony, with a more intimate collection of white brick terraced townhouses discreetly tucked away on minor roads behind the muscular civic presence of the public facing flats. Touting it as the best work they’ve ever done New Gorbals Housing Association (NGHA) are positioning the scheme not merely as the regeneration of bricks and mortar but the regeneration of a community.

Despite being but a stone’s throw away from the O2 Academy and Citizen’s Theatre and within walking distance of the city centre the immediate surrounds can nevertheless best be described as borderline, but this stands to change soon as the area gains critical mass the delivery of projects such as the new Reiach & Hall/Michael Laird’s Nautical College, Bennetts Citizen’s Theatre expansion and The Glasgow House by PRP Architects.

The first element of a new quarter, master planned by Urban Initiatives and later refined by Page\Park, it has been delivered by both Page\Park and Elder & Cannon, who brought the scheme to Stage D after being novated to the developer, Urban Union, on a design and build contract. Both practices previously collaborated on nearby Hayfield Street.

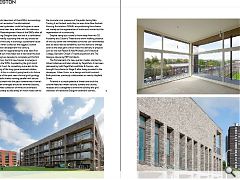

Finished in a simple palette of three tone brick the scheme features timber balcony screens and chunky recesses and is designed to evoke the solidity and grid character of traditional Glasgow tenement districts. Materials choice has been a bone of contention with planners for years as developers seek to trim costs with reconstituted stone or white render, the latter of which has been banned from the city centre. This saw Page\Park elect to proceed with a warm red brick for their portions of the build, contrasting markedly with the deep black brick favoured by Elder & Cannon.

Queried on this materials selection, a shift from Crown Street where areas of sandstone detailing were used and Oatlands which relies on the aforementioned render and reconstituted stone Page\Park’s head of architecture David Page told Urban Realm: “On the face of it we’d like it if there were still stone quarries and we could afford it - but we just can’t. Brick has long been a tradition in the city and a remarkable amount was demolished when the motorway was built. It ran through industrial areas of the city which were largely brick built but they were actually really good warehouses.” For his part Tom Connolly, director of Elder & Cannon architects, added: “It’s about trying to find a materiality which is suitable for the city.”

Page continued: “My starting point was the Commonwealth Games, it was incredibly well organised with lots of people from different countries and different sports coming together. Building a piece of city is exactly the same, you’ve got all sorts of different people and different skills; roads department, housing, funder, contractors and architects all coming together with a coherent strategy and plan. This is what it’s about, plan first rather than drop in aesthetic fragments. This would be impossible within the private sector because they’ve got to make their returns within a certain time. That’s why a private/public sector partnership can look at the longer term. The private sector can piggyback on that public sector commitment.

“It’s the same with the Merchant City regeneration, the city owned a lot of property and used that to invite the private sector in and use that property to leverage a better quality environment. If you don’t have any levers and it’s simply the private sector driving itself then it will largely look to its own short-term self-interest.”

One lesson of the past that NGHA insist they have got right this time around is maintenance, but Page is confident that a rigorous regimen of upkeep will be honoured: “There are maintenance regimes and such to ensure that this is a long-term success. Because NGHA act as factor in the maintenance of the properties their interest in maintaining quality is retained. It’s in their interests to build as well as possible in the beginning because they’re cheaper to run.”

Commenting on the design partnership at the heart of the project Page noted: “I’ve always said we’ve created a frame for their (Elder & Cannon’s) flamboyance and I actually quite like that. We were the foil for their thesis. This is about a piece of tenement fabric, even though there are no tenements left. Essentially what we’ve done is look historically at the classical way of living and made a rooted variation of the themes of tenements and the new street.” Commenting on the collaboration for his part Connolly added: “We had to. It’s not as though we’re joined from the hip, far from it. We’ve got very different points of view but a shared endeavour.”

The delivery of Laurieston comes at a crucial time for Scotland, with the rejection of independence opening the door to a debate on constitutional change, culminating a decades long appraisal of national identity and architecture which Page has helped lead. Does Page believe that nationalism is a route to design inspiration? “In a curious sort of way I think we went through all that in the 1990s up to devolution,” he says. “A lot of our work was postulating the importance of a devolved nation, so I think we’ve been through those machinations. Once you’ve gone through that with the Parliament the next thing is where you move on from there? You can’t go back to a reworking of that argument again and again and again,” he notes. “Essentially you’ve got to talk about the dynamics of what makes modern living. How do we make this an efficient, modern economy that contributes positively to the world. That’s got to be about progressive, efficient spaces which protect the environment. To me in the 1990s you had the Gordon Benson Museum of Scotland, the Parliament and the Museum of Rural Life in Loch Lomond which were all evocative of the national spirit, we’ve kind of done it.”

With a second phase, constituting a further 108 homes, set to go on site this autumn following additional master plan modifications introduced by RMJM, the Laurieston development is well on track to delivering up to 1,000 homes over the next decade - with aspirations to deliver private housing, retail, a hotel and community facilities in later phasing. It isn’t the Gorbals of old but it is a new start.

|

|

Read next: Cold War

Read previous: The Sublime in Scottish Art & Architecture

Back to October 2014

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.