Nigeria

13 Jan 2014

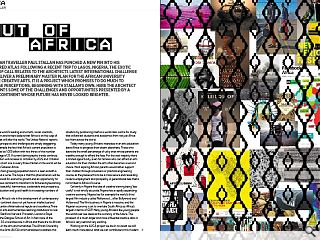

Veteran traveller Paul Stallan has punched a new pin into his battered atlas following a recent trip to Lagos, Nigeria. The exotic port of call relates to the architects latest international challenge - to deliver a preliminary master plan for the African University of the Creative Arts. It is a project which promises to do much to change perceptions, beginning with Stallan’s own. Here the architect recounts some of the challenges and opportunities presented by a dark continent whose future has never looked brighter.

Many of the world’s leading economists, social scientists, philosophers and writers believe that Africa is on the cusp of changes that will alter the world. The United Nations’ reports on Africa’s prospects and challenges are simply staggering. Take for example the fact that Africa’s current population is estimated to be 1.033 billion with two thirds of this number under the age of 25. If current demographic trends continue, the population will increase to 1.4 billion by 2025 and 1.9 billion by 2050. In short one in every three children in the world will be born in Sub Saharan Africa.Africa’s fast-growing population boom is seen as both a blessing and a curse. The hope is that this phenomenon will be a decisive boost for economic growth and an opportunity for this enormous continent to transform its fortunes by becoming even more beautiful, harmonious, sustainable and prosperous, offering education and good health to increasing numbers of people.

Despite Africa’s role in the development of contemporary culture the continent does not yet have an intellectual and academic centre ofinternational repute and excellence.There are no major arts and humanities learning institutions to rival the likes of Stanford, Harvard, Princeton, London’s Royal College or the Glasgow School of Art. In fact none of the world’s top 50 universities are in Africa and there are no African universities in the arts and humanities. The African University of the Creative Arts (AUCA) which proposes to address this situation by positioning itself as a world class centre for study that will attract students and academics from not just Africa but from across the world.

Today many young Africans interested in an arts education leave Africa to progress their dream elsewhere. Those who leave are the small percentage of ucky ones whose parents are wealthy enough to afford the fees. For the vast majority there is limited opportunity. Even for families who can afford an arts education for their children the arts often becomes a second choice. Most aspiring African parents would rather support their children through a business or practical engineering course, as they believe this to be a more secure and rewarding route to employment and prosperity. A generational bias that is not limited to Africa of course.

Certainly in Nigeria the idea of creative training being ‘less useful’ is not wholly accurate. Nigeria has a rapidly expanding creative economy. Nigeria has for example the world’s third largest film industry called Nollywood ... after Bollywood and Hollywood! The film business in Nigeria is massive, and the Nigerian economy is set to overtake South Africa as Africa’s largest in terms of GDP. Many young Africans like young people the world over see ideas as the currency of the future. The prospect of a much larger and more influential creative class in Africa is very real and very exciting.

Working on the AUCA project we are in no doubt we will learn much more about what we can contribute to this modern African renaissance. Our skills are clearly in demand. Our client and project champion is a remarkable woman called Ejemen Ojeabulu who has become a very good friend. Ej is the driving force behind this extraordinary project and involved us because of our experience in education architecture and campus master planning in both the U.K. and internationally. We hope to offer more than just an insight into higher education but a unique insight into education as a whole. We can in effect demonstrate an understanding of the lifelong learning continuum with particular reference to curriculum innovation; i.e. from child to young adult and beyond. In this project our sense is that the focus will not just be higher education but arts education in its entirety.

Although expert in educational environments working in Africa, West Africa and specifically Nigeria was new to us. Much of our work to date has therefore involved considerable research and study; that said we found the critical writing on precolonial sub Saharan African architecture to be limited. Compared with the extensive texts and observations dedicated to African art the continents architecture is poorly served. I read in one text that the lack of documents on historic African architecture was because Africa’s indigenous sub Saharan inhabitants were nomadic.

There was no need for architecture and no requirement to build monuments for a state system that did not exist. Of course there are notable legacy and religious structures but on the whole the people of central and southern Africa lived with and on the land, they had a light touch. What therefore would be our inspiration for AUCA without reference to architectural precedent?

In stark contrast and in no way a light touch the colonisation of sub Saharan Africa was to change the landscape of the continent dramatically. Along the North African coast a complex mix of Phoenician, Roman, Islamic and European influences exists due to the lands proximity to the Mediterranean, however the interior of the Dark Continent as our Victorian forefathers referred to it was transformed by the Empire builders.

In Central, East, West and South Africa invaders including the British, French, Dutch, Belgian and Portuguese made their mark. The division of Africa into many different countries that you see on the modern map is an imperial overlay. This partitioning of the country impacts on the African psyche to this day.

Fast forwarding to the 20th century it was late modernism that had the largest impact on the character of African urban environment, although not in a wholly positive way. Today, entire cities of rudimentary functional concrete construction define the African metropolis.

There have been attempts at making this generic modernism contextual by superficially decorating structures with African forms and patterns inspired by traditional art and craft. There have also been attempts to create new African aspirational commercial architecture; like the phenomenon that is Dubai where the excesses of Arabesque appliqué border on the absurd, with architecture reduced to built cartoons. Although not with the same budgets or on the same ‘bling scale’ as Dubai there are never the less many buildings in Africa that are in contention. Potato print commercialised architecture sold via stylised CGI is well established in Africa, as in other emergent economies such as China and India.

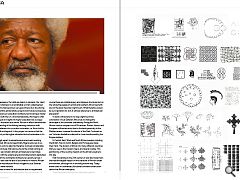

Digging deep I did find some early modern architecture that genuinely attempted to respond to the specifics of place, the diverse African natural habitat, social systems and regional culture though these are few. In this respect our challenge was set. Our AUCA project had to critically position itself as an exemplar of architecture that is contemporary and is inspired by the reality and richness of place. As AUCA fountainhead and counsel the chairman of our client body, Professor Wole Soyinka is a remarkable man and a Nobel Laureate. Professor Soyinka the first Black African to receive a Nobel award and has been recognised for his political insight, his artistic integrity and the championing of Africa and the African spirit.

Professor Soyinka’s writing has helped me to understand some of the cultural challenges that Africa faces. A principle challenge is one of boundaries and the illusions of freedom. His book African Spring considers that the original partitioning of Africa has created many of the problems that the continent now faces. Professor Soyinka idealises an Africa with a populace that moves freely across the landscape. Without complex hierarchal state systems, Africans could travel freely across the vast continent to trade, hunt and harvest the land and avoid droughts in one region and conflicts in another.

The lines now drawn on the map of Africa prevent people from responding to events with the same fluidity and sustainability as they did in the past. Whether warlords, despots, global corporations, disease or just bureaucracy Africa doesn’t function now as it once did. The point being made is not to return to the precolonial past but to inspire an understanding that what still links all Africans is a generosity of spirit and that together all Africans can make things better. The fluidity and ability to grow and evolve rests with sharing and openness. Stability and sustainability rests with generosity and equality. The quintessential point I took from Wole’s book African Spring was that spiritually Africans have a shared soul, mother Africa. Not one bit of it all of it.

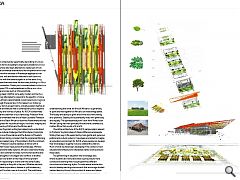

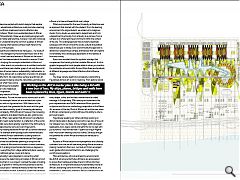

I foundthe architecture of the AUCA campus plans relevant to Professor Soyinka’s ideas of shared difference and people finding their way in life supported by more gentle and generous political and cultural systems. I have been prompted to imagine an education environment for AUCA where people can develop their knowledge in a gently inclusive collaborative fashion. Much of what we have been developing in the context of new educational architecture for interested clients revolves around these ideas.

The partitioning of education into knowledge silos where students are instructed (told) is giving way to more constructive learning that cross programmes different curriculums and learning styles. Our educational architecture aims to develop learning environments that encourage student centred learning through the provision of spaces and places that can support learning cultures, where learners learn to learn.

I have become excited with sketch designs that explore how a new educational architecture could promote a learning place for the African creative arts and in reflection also embrace Professor Wole’s more existential ideas of African harmony. Philosophically I hope we are making progress with the campus master plan premise, however I was also massively interested in understanding the common qualities of African art and reviewing what relevance these might have for the architecture of the project.

This is a profound statement but here goes ... my study of African art has changed my life and westernised view of the world. The more I read and learned of African art the more I thought that I had learned about the world in reverse. If I had started life studying the concepts embedded in African art before any other area in my education as an architect and artist I believe I would have had a better grasp of not only the world of art but also of human nature, sustainability, mathematics, in fact everything. African art is a reflection of world in its simplest most beautiful form. At a decorative surface level African art might be reduced to being colourful, naturalistic, primitive and symbolic but what I have come to understand beyond a graphic appreciation is its intellectual origins and inspiration.

A primary feature of African art is mathematics. For me this was not as obvious as it is with Islamic art for example. Islamic art and architecture is pure mathematics with no figurative form. With Islamic art the mathematical grids that generate the tile work and the great mosques are determined by grids of increasing decreasing scale and complexity. With African art however the increasing decreasing patterns and determinants are also grids but are fractal grids. When I said earlier that African art is a reflection of the world I meant quite literally it is a reflection of the world. When fractals were discovered by scientist in the 20th century they were described by some as God’s finger prints.

From my reading traditional African art is a direct extension of nature. For example anthropologists and mathematicians have documented African settlements as being based on fractal geometries. One notable mathematician Ron Eglash has claimed that this settlement planning is unique to the indigenous tribes of Africa and not evident in other continents. This interest in scaling proportionate harmonious degrees is captured in everything from village settlement plans, weaving patterns, traditional games, music and dance.

Architecturally I was interested in connecting what I understood were the determining principles of African art and incorporating them in our project. I wanted the ideas of scaling, of harmony, of growth of infinity and inclusiveness to be the genesis of our project. I wanted architecture that was African in spirit at an intellectual level, a planning system that develops according to the AUCA’s developing requirements, growing like a flower or a tree and beautiful at every stage.

What we proposed for the new University architecture was an approach that started with the student. From the learning environment of a single student, we scaled up to imagine a studio, from a studio we extended to department and from a department to a faculty, from a faculty to a campus, from a campus to a whole learning environment within the context of the city. This scaling approach has wonderful aesthetic synergies with African art but the social, cultural and political relevancies give it validity. Even economically the approach is attractive in presenting a campus architecture that can expand incrementally into a landscape dependant on the realities of time and money.

Even more wonderful are the symbolic overlays that complement the fractal grids that underlie African art. It is this graphic language that most people relate to when you mention the continents arts and crafts. Across Africa there are hundreds of different languages and tribal inflections that influence design.

The sheer variety, depth and complexity is astonishing. Figuratively African art is rich in meaning. From leafs to lizards every shape, colour and line has a narrative and a coded message. In Europe early 20th century art movements like post impressionism and DaDA referenced Africa primitive sculptures and forms as a refreshing juxtaposition to the Beaux Art excesses of the day. Much of African art and the new wave of African contemporary artists still have this ability to utter a primeval scream.

Figuratively speaking (or rather painting) working on AUCA master plan is like being a kid with a new box of toys, all my Glasgow toys, my ships, cranes, bridges, walls have been replaced by lions, tigers, lizards and leafs! No rain to deal with just sunshine. I was worried that if I spent too long in Nigeria that I would start wearing colourful clothes. Seriously though the potential for a new African architectural vernacular is exciting.

As parts of Africa become more prosperous and culturally confident I am sure we will see more young African architects making modernism their own. Just look at China’s emergent avant garde artists and architects ho are challenging the world’s preconceptions.

More architecture schools and learning environments like AUCA will ensure that future Africans are empowered to access their heritage and take the art in Africa into their architecture. It is important because fundamentally we are all African, everything came from Africa, culture, literature, art, mathematics, philosophy, mankind. Africa’s contribution to art worldwide is total.

|

|

Read next: Look Up Glasgow

Read previous: Charlotte Square

Back to January 2014

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.