Bridgeton Olympia

30 Jan 2013

A spate of new libraries to open their doors in recent months show that, internet or no, the demand for print is still strong. In the first of a triumvirate we take a look at Bridgeton’s Olympia, recently reopened by Clyde Gateway, before historian Robert Currie takes a closer look at the changing nature of cinema going down through the ages. Photography by Andrew Lee.

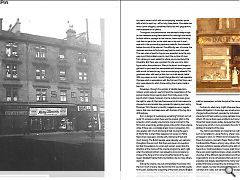

The Olympic spirit may have swept the east end of London this summer but in the east end of Glasgow the Commonwealth Games have brought about a similarly Olympian renaissance, literally in the case of Bridgeton which has just unveiled its new look Olympia, a reconfigured former cinema which now provides a mixed use space for public and commercial tenants.The cinema had lain derelict for almost 18 years before developer Clyde Gateway got hold of it, meaning anyone older than around 40 or so will have no clear memories of its history. Sadly all the seats and anything of any value or connection to this past had already gone by this time and a serious fire consumed what little remained, in addition to leaving giant gaping holes in the roof. As project architect Karen Pickering of Page\Park put it, the structure had come to resemble ‘a tired old lady with trees growing out of her head’.

Following her 18 month makeover (the original construction took just six months) a series of stacked open plan spaces have beenn inserted into the void once occupied by the main auditorium. These sit behind the retained sandstone façade whilst the principle ground floor space has been given over to Bridgeton Library, one of nine hub libraries across the city operated by Glasgow Life, which has relocated to the new building from its old premises in nearby Landressy Street (now occupied by the Glasgow Women’s Library). Taking Urban Realm on a tour of the new space Clyde Gateway’s project manager, Audrey Carlin, said: “It’s a community hub library so you can get all the services you can get at the Mitchell such as business services.”

The library also boasts the first terminal in Scotland to connect with the British Film Institute’s archives, allowing readers to browse through rare TV shows, films and adverts from yesteryear. Free to use, it’s expected that a number of schools will use it for research, amongst them St Mungos Academy, Dalmarnock Primary, Sacred Heart Primary and City of Glasgow College. “There’s a lot of stuff from the Scottish Screen Archive that hasn’t been digitised before”, noted Carlin.

Alongside this a public café nestles in full view of a reinvigorated Bridgeton Cross, itself recently upgraded by Clyde Gateway, providing a welcoming pit-stop for the growing number of people making use of Bridgeton Station.

The floor above is operated by Amateur Boxing Scotland, replete with its own full size boxing ring on a sprung floor, for use by elite athletes during the Commonwealth Games as well as members of the public who sign up for the club. Acoustically buffered from the library below there is even an eighty rung long set of monkey bars upon which the project team have been setting themselves challenges. The double height space takes advantage of a completely rebuilt interior to slice through existing floor levels, whilst full height glazing making the sport visible to the wider public outside.

Pickering added: “Before there were no windows and no way of seeing inside, so this opens it up to the street. It was a façade retention which is a shame and we really thought long and hard about how we get back the feel of the building. We were concerned that people with strong memories of the cinema would come back and find it wasn’t there anymore.”

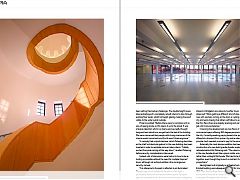

To remedy that a spiral staircase, which Pickering describes as the chief ‘architectural gesture’ in the new building, has been inserted in order to reinstate some art deco charm. “Initially we had the spiral coming all the way down”, recalled Pickering, before security considerations intervened.

Instead a lot of discussions were had as to how to be as inviting as possible without the need for multiple fireproof doors, although not without addition of an incongruous security camera.

This reference to the past is reflected in an illuminated Olympia sign which bathes the façade in white light, a particularly welcome intervention following the Olympia’s years as a darkened hulk. Its new found luminosity is relighting interest in Bridgeton as a place to be after hours. Carlin observed: “We’re getting a different kind of vibe in Bridgeton now with workers coming on the train or cycling in from the city and we’re hoping that others will follow to work in places like this. New shops are already opening and we’re starting to get a bit more sustenance.”

Crowning the development are two floors of open plan commercial space offering 360 degree panoramic views across the city. Currently awaiting paying tenants the space is being offered at a discount from prime city centre rates and will provide much needed income to pay for the social utility below.

Externally the most obvious addition has been the construction of a new build granite façade, explaining the rationale behind this Pickering said: “The columns are reflected in the new façade almost like a piano nobile, wrapping round rather than a straight flat façade. We tried to tie the two together, even though they’re such a contrast, through the proportions.”

Having been built originally as a theatre back in 1911 this B-listed building was subsequently rebuilt for cinema use in 1938. This, the buildings third major rebuild, should ensure the structures survival for a further 100 years but more importantly it has given Bridgeton back its soul.

ROBERT CURRIE, HISTORIAN

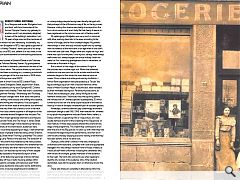

As a Glasgow east-ender, Bridgeton born and bred, with fond memories of the former Olympia Cinema, my gateway to another world, I am absolutely delighted to learn of the building’s restoration. I am 75 years of age now, but the memories of life in Bridgeton remain rich and rewarding. Incidentally, my grandfather (born Bridgeton in 1872) was a great supporter of Olympia when a Variety Theatre. I have a picture of his shop-front in Tollcross, circa 1912, and, believe it or not, there, in the shop window is an advertisement for forthcoming attractions at Olympia.

The shop was located in Easterhill Street in old Tollcross looking towards Tollcross Railway Station. My grandparents and their children lived in domestic premises at the rear of the shop accessed from within. The picture shows my two aunts, the elder, who had been scrubbing out, is wearing a sackcloth work-apron. The younger of the duo was born in 1909 which fixes the date of the picture circa 1911/12.

The tenement in which I lived at 555 London Road, Bridgeton, opposite Silvergrove Street, beyond Kerr Street, was within close distance of my local Olympia ABC Cinema and I usually visited twice weekly. There was then a customary change of programme Monday - Wednesday and Thursday - Saturday. Admission charges were: front stalls nine-pence, back stalls one shilling, front balcony one shilling and sixpence, back balcony one shilling and nine pence. As a youngster, I generally opted for the front stalls at nine-pence, but refrained from sitting at the very front row to avoid a crick in the neck.

This was a first class cinema superior in all respects to the many others scatttered around Bridgeton that included The ‘wee’ Royal in Main Street (generally referred to as a flea pit), the Arcadia in London Road, and The King’s in James Street which I seldom visited although I have interesting memories of The King’s where, at the intermission, audiences were entertained by live artistes appearing on stage. I well remember the lengthy queues of people stretched along James Street as far as Landressy Street when The King’s presented ‘The Jolson Story’ featuring Larry Parkes in the lead role. The boredom of queuing up for the cinema was relieved by the many buskers, singers, tap-dancers and instrumentalists who entertained the queues with their artistry and then went round with the hat.

Looking back, I am touched by the irony of how, despite being constantly exposed to Hollywood’s export of the American way of life featuring seemingly ordinary families living comfortably off lives in leafy housing estates within clapboard bungalows complete with spacious open-front gardens, numerous bedrooms and public rooms, bathrooms, fitted kitchens and, of course, telephones and cadillacs in the driveway - all in stark contrast to life as lived in post-war Britain and, not least, working class Bridgeton. I am amazed at the realisation that I failed to feel any sense of either envy or underprivilege despite having been literally deluged with that portrayal of the all American way of life on the big screen. However, visiting the cinema was clearly an escape from the hum-drum existence of one’s daily life that clearly it seems to have registered on the mind as some sort of fantasy world.

My upbringing in Bridgeton was very much in common with other working class kids in the area, according to the norms of the age, and far from underprivileged. My parents were always in work and duly imbued myself and my siblings with the rewards of the work ethic in an age when if one didn’t work then one didn’t eat. Wages were low, hopes ran high, and there was a job for everyone. I and my four siblings were always well turned out, always enjoyed an annual holiday ‘doon the water’ at Kirn, where my grandparents lived in retirement, or otherwise at Arbroath in Angus.

But to return to the magic of the cinema. A night at the pictures was a routine night out. Within the darkened auditorium one was soon lost to the outside world and the adrenalin began to flow when the main feature came on screen. Films in black and white produced by the British J. Arthur Rank organisation were preceeded by a ‘Tarzan’ like figure striking a big drum with a massive hammer, while those of Metro-Goldwyn Mayer, in technicolor, were heralded by their inimitable roaring lion. Paramount productions, as I recall, had a statuesque Lady Liberty like figure as their hallmark introduction. Technicolor was the big thing before the introduction of Cinemascope and subsequently 3D which turned out to be a bit of a damp squid because of the need to hold up in front of the eyes a makeshift pair of coloured glasses.

Nowadays, cinema audiences pay a seemingly exorbitant admission charge to see ONLY ONE main feature film, whereas in my youth the programme included Pathe News, trailers, a Disney cartoon, a supporting film or ‘wee picture’, as it was usually termed, all prior to the screening of the ‘Big picture’ or main feature. In those days people entered the cinema at any stage of the programme. This meant they continued to sit on after the end of the ‘Big picture’; to catch up with what they had missed at the beginning of the performance, and then sit on until the end, thereby enjoying a second viewing of all that they had seen before, and at no extra cost.

Olympia, unlike other cinemas in the area, employed a uniformed commissionaire, complete with coat and appropriate headgear who was always visible at front-of house. Indeed, as I recall, all staff were uniformed including the usherettes who, with the aid of torchlight, guided members of the audience to their seat. The torch also came into use when seeking to identify any rowdies in the audience who, if the situation demanded, were told to quieten down or otherwise shown the door.

There was always an usherette in attendance within the auditorium kitted-out with a tray suspended over her shoulders from whence she conducted the sale of ice cream, soft drinks and Butterkist (as popcorn was called in those days). Vanilla ice cream came in a tub with accompanying wooden spoon with which to sup it up - all for only three pence. Chocolate ices which came wrapped, sometimes flavoured with peppermint, were available for six pence.

Throughout the performance, one tended to keep an eye on the usherette selling these dainties for, although she would be held within a spotlight at the interval, there would be a big rush then to get to her, so the ideal was to slip out of one’s seat and in the surrounding darkness make for the usherette before the rush of the interval. The difficulty was, of course, the darkness and how to find one’s way back to one’s own seat. This was when a head for figures was essential, since the only way round that problem was to count the number of rows from where you were seated to where you encountered the Usherette. But there was a problem for she was not a static figure within the auditorium. Many’s the time it took longer to get back to your seat than anticipated and whoever you were with would be heard to say, to an accompanying wheesht! ‘for goodness sake, whit kept ye this choc ice is jist aboot meltin’. With ice-cream in mind, I mustn’t forget Bonini’s Cafe opposite Olympia which in association with the Fish and Chip Shop next door were places to which those exiting the cinema made a bee-line.

Nowadays, through the wonder of satellite television, millions world-wide can see first hand the presentation of the annual cinema Oscar awards direct from Hollywood. In the age of which I speak, however, cinema audiences were given the right to vote. At Olympia there was a list of nominations to choose from and a ballot box provided for placing one’s entry. Moreover, ‘Film Review’ a monthly magazine was on regular sale so that one could keep pace with the lives of the big stars of Broadway.

Am I in danger of overlooking something? Almost, but not quite! On occasions when there was the merest glitch in the projector, which usually occurred at a crucial moment in the film’s plot, a seemingly endless groan arose within the audience while, if there was a complete break-down in projection, this was greeted with much stamping of feet. During the years of World War 2 when Hitler appeared on screen on Pathe News there were jeers, whistle calls, stamping of feet and much booing. The British people were naturally very patriotic throughout the war such that there was never any question but that the audience, to a man and woman, would stand to attention at the closing of the cinema programme each night when the national anthem was played to an accompanying image of the King and for some time afterwards of the new Queen Elizabeth before that long tradition, like so many others, declined.

Exiting the cinema, one was immediately thrust back into the hum-drum of every day life and the first sound that usually hit my ears, besides the screeching of the trams around Bridgeton Cross and the Poor Man’s Umbrella, was the sound of the news-vendor’s inimitable cry of ‘Times, News and Citi-zen!’ as he sold his newspapers outside the pub at the corner of Olympia Street.

Contrary to what many might otherwise have others believe, Bridgeton in those days was a lively environment, charged with excitement, peopled by individuals who were characters. All hard-working, some perhaps more so than others. Of course there were problems but none to rival those that beset society today, because then there was work for everyone which, in turn, provided a focus for the natural abilities of residents of the area.

The district was literally an industrial hub with companies such as Templeton’s Carpet Factory, where I was personally privileged to work, Sir William Arrol’s Engineering Company, Mavor & Coulson’s. Hannah’s Paper Works. R &W. Ritchie, Cardboard Box Makers, among many others, that supported the local workforce besides attracting the skills of workers beyond our local boundaries. It was a great time to be alive, there was good neighbourliness, a lively social life within churches of the different denominations and their associated organisations, and a camaraderie that was lost when the populace was largely decanted to the many new housing estates that duly encircled the city at large. In the time of which I speak, we may have lacked computers, mobile phones, iPhones and iPads, but we had the great escape of a night at the pictures and above all our very own Olympia at the heart of the community.

|

|

Read next: Ibrox

Read previous: Kendram House

Back to January 2013

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.